|

|

|

| Adult, Mendocino County |

Adult, Siskiyou County © Noah Morales |

|

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Mendocino County |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Mendocino County |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Mendocino County |

|

|

|

|

|

| Subadult in shed, northeast Sonoma County © Luke Talltree |

Adult, Mendocino County |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile, northeast Sonoma County © Luke Talltree |

Juvenile, Mendocino County |

Juvenile, Mendocino County |

|

|

|

|

Adult without dorsal or lateral stripes,

Del Norte County © Alan Barron

|

This Humboldt County adult is nearly stripeless and patternless.

© Spencer Riffle |

Adult basking in a river,

Mendocino County

© Rachel Sowards Thompson |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Humboldt County coast

© Teejay ORear |

A neotenic Coastal Giant Salamander can be seen at the upper right with an Oregon Gartersnake on the left.

© Kirsty Coulter |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Intergrades |

|

|

|

|

| Adult intergrade, Marin County. |

Adult intergrade, Marin County. |

Adult intergrade, Marin County. |

Adult from Marin County Headlands, just northwest of the Golden Gate Bridge © Zach Lim |

North of the San Francisco Bay, there is a very large intergrade range between T. a. hydrophilus, T. a. atratus, and T. a. zaxanthus. The snakes in this area were formerly classified as T. a. aquaticus (previously T. couchii aquaticus.)

This subspecies is no longer recognized. More pictures and information about these intergrades can be seen here. |

| |

|

| Feeding Behavior |

|

|

|

|

| An Oregon Gartersnake eating a fish in Trinity County. © Kevin Andras. |

|

|

|

An Oregon Gartersnake eats a fish in Mendocino County.

© Linda Bostwick |

Adult eating a trout, Shasta County

© Thomas Kavenaugh |

| |

|

"

We were just about to leave after lunch when I saw this guy slip into the water out of the corner of my eye. I started changing lenses knowing he would come up nearby as the pool was only 4 feet across. You can imagine my surprise to see him come up with this very angry trout. I took a number of shots as they fought. They were in still water about 4 inches down. They even went over a 2 foot waterfall but the snake never let go. Eventually he got his back end up on a rock, slowly dragged the fish out and eventually began swallowing it."

-

Thomas Kavenaugh |

|

|

|

|

Oregon Gartersnake eating a neotenic Coastal Giant Salamander, Dicamptodon tenebrosus, in Trinity County.

© Ben Witzke |

|

|

|

|

|

An intergrade Aquatic Gartersnake in Napa County eats a frog (either a California Red-legged Frog or a Foothill Yellow-legged Frog.)

© Pamela Delgado |

Adult gartersnake of undetermined species eating a banana slug in Mendocino County. (It's either a Coast Gartersnake or an Oregon Gartersnake.)

© Gail Jackson |

| |

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Mendocino County |

Habitat, Mendocino County. These small pools of water along the edge of a wide riverbank in summer, contained Foothill Yellow-legged Frogs and tadpoles, Bullfrogs, and Oregon Gartersnakes. |

Habitat, Mendocino County |

Habitat, Humboldt County coast

© Teejay ORear |

More pictures of this animal and its natural habitat are available on our Northwest Herps page.

|

| Short Video |

| |

|

|

| |

An Oregon Gartersnake basks on a rock in a

River in Mendocino County, and swims away. |

|

|

|

|

|

Description |

Not Dangerous - This snake may produce a mild venom that does not typically cause death or serious illness or injury in most humans, but its bite should be avoided.

Commonly described as "harmless" or "not poisonous" to indicate that its bite is not dangerous, but "not venomous" is more accurate since the venom is not dangerous. (A poisonous snake can hurt you if you eat it. A venomous snake can hurt you if it bites you.)

Long-considered non-venomous, discoveries in the early 2000s revealed that gartersnakes produce a mild venom that can be harmful to small prey but is not considered dangerous to most humans, although a bite may cause slight irritation and swelling around the puncture wound. Enlarged teeth at the rear of the mouth are thought to help spread the venom.

|

| Size |

Adults are 18 - 40 inches long (46 - 102 cm). Most snakes encountered are generally 18 - 28 inches long (46 - 71 cm).

Neonates are 7 - 10 inches ( 18 - 25 cm).

|

| Appearance |

A medium-sized slender snake with a head barely wider than the neck and keeled dorsal scales.

Some average scale counts: Average of 8 upper labial scales, 6 and 7 not enlarged. 11 lower labial scales.

Rear pair of chin shields is longer than the front.

The internasals are longer than they are wide and pointed in front.

Average of 19 or 21 scales at mid-body.

|

| Color and Pattern |

Ground color is gray, olive-gray, or brownish.

This snake may have a light stripe on the back and a light stripe along the lower part of each side.

The dorsal stripe and the side stripes may be absent or obscured, not contrasting sharply with the ground color, leaving a checkered appearance instead of striped. There are usually alternating dark spots on the sides.

The throat is light in color.

The underside is light and unmarked with a pinkish or purplish tint toward the tail. |

Key to Identifying California Gartersnake Species

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

A highly-aquatic snake, able to remain underwater, but also found away from water.

Active during the day, and after dark during very hot weather.

Can be active most of the year when conditions allow, but primarily found spring through fall.

|

| Defense |

When threatened, this snake will often escape into water, hiding on the bottom. If it is frightened when picked up, it will often strike repeatedly and release feces from the cloaca and expel musk from anal glands.

|

| Diet and Feeding |

Probably eats mainly amphibians and their larvae, including frogs, tadpoles, and aquatic salamander larvae (newts and giant salamanders, Taricha and Dicamptodon ), but small fish are also eaten. Captives have also taken small rodents. Leeches may also be consumed - I saw a recently-captured T. a. zaxanthus regurgitate two leeches.

Adults tend to forage actively. Neonates are sit-and-wait foragers. Juveniles practice both types of foraging.

Toxic Newts

This species has been observed eating adult Pacific Newts (genus Taricha) which are deadly poisonous to most predators.

The Bay Area is the Center of an Evolutionary Race Between Hungry Snakes and Toxic Newts.

by Anton Sorokin. Bay Nature, April 6, 2022

Gartersnakes Can Become Poisonous

There is evidence that when Common Gartersnakes (Thamnophis sirtalis) eat Rough-skinned Newts (Taricha granulosa) they retain the deadly neurotoxin found in the skin of the newts called tetrodotoxin for several weeks, making the snakes poisonous (not venomous) to predators (such as birds or mammals) that eat the snakes. Since California Newts (Taricha torosa) also contain tetrodotoxin in their skin, and since gartersnake species other than T. sirtalis also eat newts, it is not unreasonable to conclude that any gartersnake that eats either species of newt is poisonous to predators.

Williams, Becky L.; Brodie, Edmund D. Jr.; Brodie, Edmund D. III (2004). "A Resistant Predator and Its Toxic Prey: Persistence of Newt Toxin Leads to Poisonous (Not Venomous) Snakes." Journal of Chemical Ecology. 30 (10): 1901–1919.) https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEC.0000045585.77875.09

|

| Reproduction |

Courtship has been observed during March and April.

Females are ovoviviparous - they carry the eggs internally until the young are born live from late summer to early fall.

|

| Habitat |

Creeks, streams, rivers, small lakes and ponds, in woodland, brush and forest. Seems to prefer shallow rocky creeks and streams.

|

| Geographical Range |

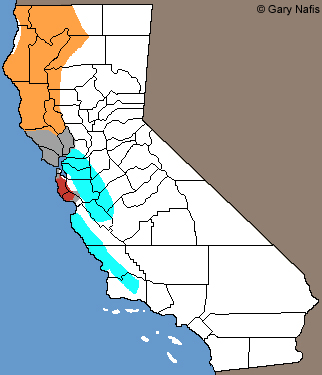

This subspecies, Thamnophis atratus hydrophilis - Oregon Gartersnake, ranges from northern Sonoma County north along the coast to Douglas County, Oregon, and east throughout the north coast ranges and to the lower Pit River area. It is absent from much of the coast around Humboldt County.

The species Thamnophis atratus - Aquatic Gartersnake, ranges from Santa Barbara County north through the coast ranges into southwest Oregon.

|

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

This snake is known to hybridize with T. couchii in Shasta County. For a long time T. atratus was considered a subspecies of T. couchii. In 1987 it was classified as a distinct species.

North of the San Francisco Bay, there is a very large intergrade range between the Oregon Gartersnake and T. a. atratus or T. a. zaxanthus. The snakes in this area were formerly classified as T. a. aquaticus (previously T. couchii aquaticus.)

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Thamnophis couchi hydrophilus - Oregon Garter Snake (Stebbins 1985, 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Thamnophis couchi hydrophila - Oregon Garter Snake (Stebbins 1966)

Thamnophis elegans hydrophila (Stebbins 1954)

Thamnophis elegans hydrophila - Oregon Gartersnake (Fitch 1936)

Oregon gray garter snake

Moccasin

Water snake

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| Not known to be threatened, but gartersnakes have been negatively impacted by competition with introduced bullfrogs in some areas. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Colubridae |

Colubrids |

Oppel, 1811 |

| Genus |

Thamnophis |

North American Gartersnakes |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species |

atratus |

Aquatic Gartersnake |

(Kennicott, in Cooper, 1860) |

Subspecies

|

hydrophilus |

Oregon Gartersnake |

Fitch, 1936 |

|

Original Description |

Thamnophis atratus - (Kennicott, 1860) - in Cooper, Expl. Surv. R.R. Miss. Pacific, Vol. 12, Book 2, Pt. 3, No. 4, p. 296

Thamnophis atratus hydrophilus - Fitch, 1936 - Amer. Midland Nat., Vol. 17, p. 648

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Thamnophis - Greek - thamnos = shrub or bush + ophis = snake, serpent

atratus - Latin = clothed in black, mourning - refers to the dark dorsal color

hydrophilus - Greek - hydro = water + philus = loving - refers to the snakes aquatic proclivities

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

| Other California Gartersnakes |

T. a. atratus - Santa Cruz Gartersnake

T. a. zaxanthus - Diablo Range Gartersnake

T. couchii - Sierra Gartersnake

T. gigas - Giant Gartersnake

T. e. elegans - Mountain Gartersnake

T. e. terrestris - Coast Gartersnake

T. e. vagrans - Wandering Gartersnake

T. hammondii - Two-striped Gartersnake

T. m. marcianus - Marcy's Checkered Gartersnake

T. ordinoides - Northwestern Gartersnake

T. s. fitchi - Valley Gartersnake

T. s. infernalis - California Red-sided Gartersnake

T. s. tetrataenia - San Francisco Gartersnake

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Snakes of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bartlett, R. D. & Alan Tennant. Snakes of North America - Western Region. Gulf Publishing Co., 2000.

Brown, Philip R. A Field Guide to Snakes of California. Gulf Publishing Co., 1997.

Ernst, Carl H., Evelyn M. Ernst, & Robert M. Corker. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2003.

Taylor, Emily. California Snakes and How to Find Them. Heyday, Berkeley, California. 2024.

Wright, Albert Hazen & Anna Allen Wright. Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1957.

Rossman, Douglas A., Neil B, Ford, & Richard A. Siegel. The Garter Snakes - Evolution and Ecology. University of Oklahoma press, 1996.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This snake is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

Orange: Range of this subspecies in California

Orange: Range of this subspecies in California