|

| Adults |

|

|

| Small adult, Humboldt County |

Small adult, Humboldt County |

|

|

|

|

| Small adult, Humboldt County |

Pale unmarked underside of small adult,

Humboldt County |

|

|

|

|

| Small adult, Humboldt County |

Small adult, coastal redwoods, Del Norte County |

Small adult, coastal redwoods,

Del Norte County |

|

|

|

|

Adult, coastal redwoods,

Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

Adult, 5,300 ft., eastern Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

Adult, coastal redwoods,

Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

Adult, found approximately 150 meters from a creek in Humboldt County

© Alyssa Semerdjian

|

|

|

|

|

Large adult, Humboldt County

© Patrick Briggs |

Adult in situ, Humboldt County

© Spencer Riffle |

Adult in situ, Humboldt County

© Spencer Riffle |

Adult in situ, Humboldt County

© Spencer Riffle |

|

|

|

Adult, Humboldt County

© Marcus Rehrman |

Adult, Humboldt County

© Zchary Cava |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Neotenic Adults (Paedomorphs) |

|

|

|

|

| Neotenic adult in a Trinity County creek © Kirsty Coulter |

Upper right is the same neotenic Trinity County adult seen in the pictures to the left along with an Oregon Gartersnake on the left of the picture. © Kirsty Coulter |

Large neotenic adult in water, 5000 ft., Trinity Mountains, Siskiyou County |

|

|

|

|

| Large neotenic adult, Mendocino County. (Note the dark claw-like growths on the back toes.) © Molly Rinaldi |

Large captive neotenic

adult in an aquarium |

|

|

|

|

| Paedomorph in a high-elevation lake in Trinity County © Spencer Riffle |

Paedomorphs in a high-elevation lake in Trinity County © Spencer Riffle |

Short Video of a neotenic salamander in water, Siskiyou County, pumping its gills and gulping air. © Ryan Aberg |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Aquatic Larvae |

|

|

|

|

| Large larva in water, Del Norte County |

|

|

|

|

| Very small larva in water, Del Norte County |

|

|

|

|

| Large larva in creek, Del Norte County |

Aquatic larva temporarily out of water to show size, Humboldt County |

Larva removed from water temporarily for photograph on land,

Del Norte County |

Larva in a muddy seep in

Mendocino County © Evan Mehta |

|

|

|

|

Larva, Humboldt County

© Evan Mehta |

Larva in water, Humboldt County

© Spencer Riffle |

Short Video of a Coastal Giant Salamander larvae shown walking and swimming in shallow water and on stones next to a small stream. |

Short Video of a tiny larval Dicampton in water that shows the gills working |

| |

|

|

|

| Eggs |

|

|

|

|

| These pictures show a recently-decapitated female Coastal Giant Salamander in Mendocino County. You can see her unlaid eggs spilling out of the wound. After they are produced and before they are laid, the eggs fill up the salamander's body cavity. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Feeding |

|

|

|

|

| Adult eating a Banana Slug in Humboldt County © Grayson B. Sandy |

|

|

|

|

|

| Large larva in water, Del Norte County after regurgitating a worm it had eaten |

Adult eating a banana slug, Humboldt County © Spencer Riffle |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Predators |

|

|

|

|

Oregon Gartersnake, Thamnophis atratus hydrophilus, eating a neotenic Coastal Giant Salamander in Trinity County.

© Ben Witzke |

|

|

|

|

|

| These two Coastal Giant Salamanders were found locked in combat beside a coastal creek in Humboldt County in mid July in what is probably an attempt by the large salamander to eat the smaller salamander. The smaller salamander bites onto the large salamander's leg while the large salamder bites onto the smaller salamander's body. © Alyssa Semerdjian |

|

|

| |

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Del Norte County |

Habitat, Del Norte County |

Habitat, Humboldt County |

Habitat, Humboldt County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Humboldt County |

Habitat, 5,000 ft., Trinity Mountains, Siskiyou County

|

Habitat closeup, 5,000 ft., Trinity Mountains, Siskiyou County |

Habitat, Del Norte County |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, Mendocino County

|

Most Coastal Giant Salamanders are found within about 50 meters of a creek, but sometimes they wander farther from water. One was found wandering in daylight at this location approximately 150 meters above a creek in Humboldt County.© Alyssa Semerdjian |

Habitat, Trinity County © Kirsty Coulter |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

| Short Video of a Coastal Giant Salamander larvae shown walking and swimming in shallow water and on stones next to a small stream. |

Short Video of a tiny larval Dicampton in water that shows the gills working |

Short Video of a neotenic salamander in water, Siskiyou County, pumping its gills and gulping air. © Ryan Aberg |

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 2 1/2 to 6 4/5 inches long (6.25 - 17 cm) from snout to vent, and up to 13 inches (34 cm) in total length.

Neotenic larvae may grow to almost 14 inches (35 cm.)

This is the largest terrestrial salamander in North America.

(Hellbenders are much larger, but they spend most of their adult lives living in water.)

|

| Appearance |

The body is large and robust with a massive head and stout limbs.

The tail is flattened from side to side.

Transformed adults have 12 - 13 indistinct costal grooves.

Larvae are stream-type with tail fins that extend forward only to the hind limbs.

There is often heavy black mottling.

Gills are short, bushy, and dull red. |

| Color and Pattern |

The ground color of the body is dark brown to near black overlaid with light brown spotting or fine-grained marbling that gives the salamander a camouflaged appearance.

Very old animals may lose their pattern except on the head.

The venter is white to light gray, sometimes dark.

|

| Comparison With California Giant Salamander |

Dicamptodon ensatus, California Giant Salamander, is very similar in appearance to D. tenebrosus.

As far as I can determine, the only field mark that is useful to tell one species from the other is the presence of marbling on the chin and throat of D. ensatus, which is absent on D. tenebrosus, and possibly the underside, which is whitish on D. ensatus and gray to tan on D. tenebrosus.

According to Stebbins & McGinnis 2012, both species are similar in body length but D. tenebrosus has a

smaller head, shorter limbs, fewer teeth in the uper jaw, a darker body color both dorsally and ventrally, and the marbling pattern tends to be finer.

Stebbins, 2003, says that the "dark marbling and flecking usually does not extend onto underside of throat and limbs" and that there are "dark flecks and blotches on throat and underside of legs" of D. ensatus and that "Marbling on chin notable in southern part of range."

Fellers and Kuchta in

Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest, 2005 state it this way:

On D. ensatus:

"Marbling or blotching on lower jaw often extends onto the chin, throat and underside of the forelimbs and pectoral girdle."

On D. tenebrosus:

"Adult Coastal Giant Salamanders do not have marbling that extends beyond the lower jaw onto the chin or throat.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

A member of family Dicamptodontidae - Giant Salamanders, and the genus Dicamptodon - Pacific Giant Salamanders, whose members are large in size with heavy, stocky bodies.

Dicamptodon have two distinct life phases:

- Larvae are born in the water where they swim using an enlarged tail fin and breathe with filamentous external gills.

- Aquatic larvae transform into four-legged salamanders that live on the ground and breathe air with lungs.

Neotenic adults (paedomorphs) which retain their gills and continue to live in water are found in many populations.

These gilled adults may outnumber transformed individuals.

|

| Activity |

This salamander is nocturnal, but also active in daylight during wet conditions.

Adults are typically found within 50 meters of streams.

Terrestrial adults often remain in underground retreats, emerging to forage on the forest floor on rainy nights and during daylight in wet periods in winter.

They are sometimes seen walking on forest trails in daylight and on paved roads near streams on rainy nights, especially during the first heavy Fall rains in November and December. Adults are also found under rocks in streams and under objects on the ground that retain moisture such as rocks, logs, and artificial cover objects.

Post-metamorphs sometimes return to streams when terrestrial conditions become hot and dry. |

| Defense |

Large adults are capable of delivering a painful bite.

Other defenses include arching the body and lashing the tail and excreting noxious skin secretions. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Giant salamanders will consume anything that they can overpower and fit in their mouth, including a variety of invertebrates such as sowbugs, pillbugs, worms, and slugs, and small vertebrates such as small rodents, lizards, small snakes, and salamanders, including other Giant salamanders (and Northwestern Salamanders - Ambystoma gracile, which produce an alkaloid toxin - Rombough, Herpetological Review 48(1), 2017).

Eggs or embryos have been found in large larvae and terrestrial adult giant salamanders.

Giant salamanders are sit-and-wait predators. When prey comes near they lunge quickly to grab the prey with their mouth and crush it with their jaws.

Aquatic larvae feed on small aquatic invertebrates including insects and larvae, mollusks, and crayfish, and small fish hatchlings. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic. Fertilization is internal.

Females reach sexual maturity in 5 to 6 years.

Mating occurs mostly in spring, usually in May, but later in the hear at high elevations. Breeding may also occur in the Fall.

Terrestrial males and females move from their terrestrial hiding places to a stream in which to breed..

According to Nussbaum et al, 1983, observations of Dicamptodon in captivity and in the field suggests that courtship takes place in "hidden water-filled nest chambers beneath logs and stones or in crevices.

Males deposit up to 16 spermatophores.... Females pick up one to a few of the sperm caps with their cloacas and deposit their entire clutch of 135 to 200 eggs (larger females deposit more eggs) in the nest chamber. The eggs are attached singly, side-by-side, usually on the roof of the nest chamber."

Only a few nest sites have been observed in the wild.

The female stays with the eggs to guard them until they hatch, usually in November and December, or in 6 to 7 months, during which time she does not eat.

A female probably does not breed more than once every two or more years because of the long time she spends with her eggs.

"The function of maternal care is not fully understood, but prevention of egg cannibalism seems to be one function." Eggs or embryos have been found in large larvae and terrestrial adult giant salamanders which indicates that they are a threat to a nest site. |

| Larvae and Young |

Larvae hatch in water and transform to a terrestrial form in probably about 18 - 24 months after hatching, depending on environmental conditions and the size and permanence of the stream.

Larvae live on their yolk for 3-4 months after hatching then they feed on invertebrate prey and small amphibian larvae.

Some larvae may overwinter and transform in their third year.

Young larvae are found in still water near the shoreline, often under small rocks and leaf litter.

Older larvae are found in the main stream channel.

Larvae are more abundant than transformed adults.

Larvae can be found exposed in the water at the edge of a stream at night by shining a light at the water.

Recently metamorphosed juveniles move out of streams to the surrounding habitat during wet periods.

|

| Habitat |

Occurs in wet forests in or near clear, cold streams and rivers, mountain lakes, and ponds. Takes shelter under rocks, logs, in logs, and in burrows and root channels. Population densities are highest in creeks with many large stones. Larvae frequent clear cold streams, creeks, and lakes and can be found under rocks and leaf litter in slowly moving water near the banks or exposed in the water at night.

|

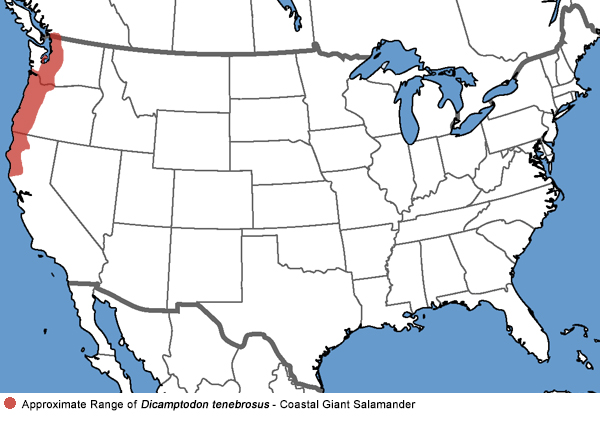

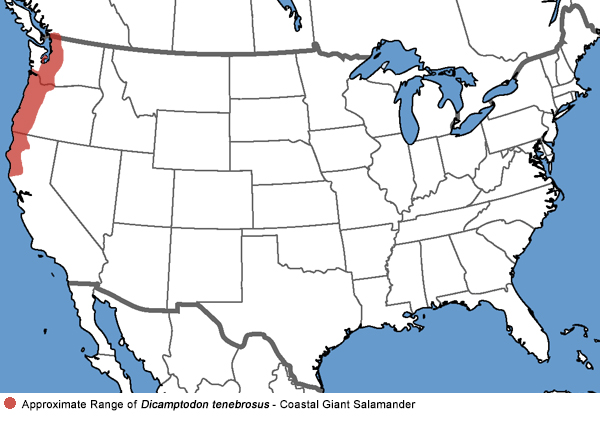

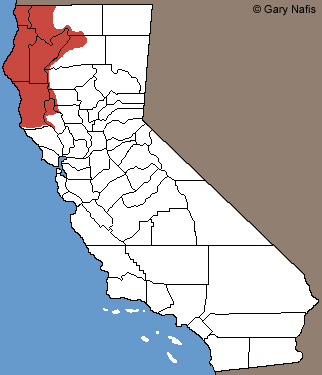

| Geographical Range |

Occurs in California from Mendocino County near Point Arena, north along the coast and into the north coast mountain ranges as far east as Shasta Reservoir, Shasta County, and McCloud, Siskiyou County, and north to the Oregon border.

From there it ranges north west of the Cascade mountains (and east of the crest in a few locations) into extreme southwestern British Columbia, but is absent from the Olympic Peninsula in Washington.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Occurs from sea level to near 7,000 ft. but mostly below 3,100 ft.

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

In 1989 the species Dicamptodon ensatus, was split into 3 species when evidence showed that Dicamptodon from Sonoma County south were genetically distinct from those to the north and from Dicamptodon in Idaho and Montana.

The northern species became Dicamptodon tenebrosus.

The southern species became Dicamptodon ensatus - California Giant Salamander.

The eastern species became Dicamptodon aterrimus - Idaho Giant Salamander.

The fourth species of Dicamptodon, Dicamptodon copei - Cope's Giant Salamander, was not changed.

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Dicamptodon tenebrosus - Pacific Giant Salamander (Stebbins 2003, 2012)

Dicamptodon ensatus - Pacific Giant Salamander (Bishop 1943, Stebbins 1954, 1966, 1985)

Dicamptodon ensatus - Marbled Salamander (Storer 1925)

Ambystoma ensatum (Dunn 1920)

Ambystoma tenebrosum (Stejneger and Barbour 1917)

Ambystoma ensatum - Marbled Salamander - Oregon Salamander (Chondrotus tenebrosus; Amblystoma tenebrosum; Dicamptodon ensatus; Xiphnura tenebrosa; Chondrotus lugubris) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Triton ensatum (Van Denburgh 1916)

Dicamptodon ensatus (Strauch 1870)

Xiphonura tenebrosa (Girard 1858)

Amblystoma tenebrosum (Cope 1867)

Triton ensatus (Eschscholtz 1833)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| The historical distribution of this salamander has probably not declined, though there certainly has been some localized extirpation from urbanization and some fragmentation within the range mostly due to forestry practices. Studies indicate a long-term decline in populations after logging of old-growth forests. D. ensatus is far more abundant in streams without a lot of silt than in streams that have become heavily silted due to logging or other alteration of the land above the stream. Creek sedimentation eliminates access to cover under rocks in the stream bed which is critical habitat. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Dicamptodontidae |

Giant Salamanders |

Tihen, 1958 |

| Genus |

Dicamptodon |

Pacific Giant Salamanders |

Strauch, 1870 |

Species

|

tenebrosus |

Coastal Giant Salamander |

(Baird and Girard, 1852) |

|

Original Description |

Baird and Girard, 1852 - Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 6, p. 174

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Dicamptodon - Greek = two curved, bent teeth, referring to doubly curved teeth

tenebrosus - Latin - tenebrosus = dark, gloomy — possibly refers to the color or habitat

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related California Salamanders |

California Giant Salamander - Dicamptodon ensatus

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bishop, Sherman C. Handbook of Salamanders. Cornell University Press, 1943.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Petranka, James W. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Corkran, Charlotte & Chris Thoms. Amphibians of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, 1996.

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

Leonard et. al. Amphibians of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, 1993.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This salamander is not included on the Special Animals List, meaning there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California according to the California Department of Fish and Game.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|

Red: Range in California

Red: Range in California