|

|

|

|

| Adult, Mono County © Keith Condon |

Adult, Mono County © Keith Condon |

Adult, Mono County © Ken Griffiths |

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Inyo County. © Seth Coffman |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile (in shed) from the Kern Plateau, Tulare County. |

|

|

|

Adult, Mono County © Keith Condon

|

Adult, Mono County © Keith Condon |

Adult in an Inyo County canal

© Ceal Klinger |

|

|

|

| Adult, 7,315 ft. elevation Bodie Hills, Mono County © William Flaxington |

Adult, 6,300 ft. elevation Tulare County near Johnsondale © William Flaxington |

Adult, 6,300 ft.elevation Tulare County near Johnsondale © William Flaxington |

| |

|

|

| Wandering Gartersnakes From Outside California |

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Spokane County, Washington |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Park County, Wyoming

(More pics from the Northwest) |

Adult, Coconino County, Arizona

(More pics from the Southwest) |

|

|

|

| Albino or Amelanistic adult, Bannock County, Idaho © Patrick Briggs |

In some areas, Wandering Gartersnakes overwinter in large groups. Here you can see a mass emergence of Wandering Gartersnakes and Valley Gartersnakes in early May, Lincoln County, Wyoming.

© Leslie Schreiber

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Thurston County, Washington |

Dark nigrescens variation,

Pierce County, Washington |

Dark nigrescens variation,

Pierce County, Washington |

| |

|

|

| |

Adult, Washington County, Utah

© Yuval Helfman |

|

| |

|

|

| Intergrades |

|

|

|

Intergrade of T.e.elegans and

T. e. vagrans.

Found in northern Siskiyou and Modoc counties and in south central Oregon, this intergrade was once considered a unique subspecies: Thamnophis elegans biscutatus - Klamath Gartersnake.

More pictures of this intergrade snake can be viewed here. |

This snake from Jackass Meadows in the Sierra Nevada mountains, Tulare County, is an intergrade of T.e.elegans and T. e. vagrans. © Rob Schell

Intergrades of these two subspecies occur along the southern and southeastern edge of the Sierras.

|

|

|

|

This snake from east of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in Mono County is a mix of T.e.elegans and T. e. vagrans.

© Ryan Sikola |

Adult, 8,000 ft. east side of the Warner Mountains, Modoc County

© Michael Crews |

|

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

| Habitat, creek east side of Sierra Nevada Mountains, Mono County |

Habitat, small creek, east side of Sierra Nevada Mountains, Mono County |

Habitat, (a small trickle in coniferous forest after a forest fire) 6,500 ft., Kern Plateau, Tulare County |

| |

|

|

| |

Habitat, Inyo County |

|

| |

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

| A melanistic Wandering Gartersnake found in Washington State. |

Wandering Gartersnakes found beside a creek in the mountains of Arizona. |

|

|

|

|

|

Description |

Not Dangerous - This snake may produce a mild venom that does not typically cause death or serious illness or injury in most humans, but its bite should be avoided.

Commonly described as "harmless" or "not poisonous" to indicate that its bite is not dangerous, but "not venomous" is more accurate since the venom is not dangerous. (A poisonous snake can hurt you if you eat it. A venomous snake can hurt you if it bites you.)

Long-considered non-venomous, discoveries in the early 2000s revealed that gartersnakes produce a mild venom that can be harmful to small prey but is not considered dangerous to most humans, although a bite may cause slight irritation and swelling around the puncture wound. Enlarged teeth at the rear of the mouth are thought to help spread the venom.

|

| Size |

Thamnophis elegans measures 18 - 43 inches in length (46 - 109 cm).

|

| Appearance |

A medium-sized slender snake with a head barely wider than the neck and keeled dorsal scales.

Some average scale counts:

Average of 8 upper labial scales, occasionally 7, scales 6 and 7 are enlarged, higher than wide.

Average of 10 lower labial scales.

The front and rear pair of chin shields are equal in length.

The internasals are wider than long and not pointed in front.

Average scale count at mid-body is 21, rarely 19. |

| Color and Pattern |

Ground color is gray, brown, or greenish and there are typically light dorsal and lateral stripes.

The dorsal stripe is yellow, brown, or orangish, but black markings on the edges may make it appear irregular or a series of dark and light dots.

The dorsal stripe also fades on the tail.

The sides are checkered with black markings.

Occasionally these markings will fill in most of the sides between stripes.

The underside is light with scattered black markings, often concentrated in the center.

The underside may also be black except on the throat and tail.

There is a melanistic phase of this snake in the Puget Sound area and in British Columbia.

Look here to see a brick red phase from the Sedona area of Arizona. |

Key to Identifying California Gartersnake Species

|

| Life History and Behavior |

| Active in daylight. Chiefly terrestrial - not as dependant on water as other gartersnake species, but more likely to be found near water. When frightened, this species will sometimes seek refuge in vegetation or ground cover, but it will also crawl quickly into water and swim away from trouble. If frightened when picked up, this snake will often strike repeatedly and release cloacal contents and musk. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Western Terrestrial Gartersnakes - Thamnophis elegans - eat a wide range of prey (among the widest of any snake species - Rossmann, et al. 1996.) The prey depends on the size of the snake (large snakes tend to eat larger prey, small snakes can only eat smaller prey) and what prey is available. Populations found on the humid North Coast where slugs are abundant are genetically predisposed to eat slugs, while populations in dryer areas where slugs are less common refuse to eat slugs when they are offered. (Rossmann, et al. 1996.)

Diet includes: invertebrates such as slugs, leeches, snails, and earthworms; fish; amphibians - tadpoles, frogs, (and probably salamanders); snakes and lizards; birds; and small mammals such as mice and voles.

Toxic Newts

Thamnophis elegans terrestris has been found in San Luis Obispo County eating Taricha torosa, which are deadly poisonous to most predators.

(Feldman, Hansen, & Sikola. Herpetological Review 51[3] 2020.)

It's possible that T. e. vagrans is also able to develop a resistance to newt toxins.

The Bay Area is the Center of an Evolutionary Race Between Hungry Snakes and Toxic Newts.

by Anton Sorokin. Bay Nature, April 6, 2022

Gartersnakes Can Become Poisonous

There is evidence that when Common Gartersnakes (Thamnophis sirtalis) eat Rough-skinned Newts (Taricha granulosa) they retain the deadly neurotoxin found in the skin of the newts called tetrodotoxin for several weeks, making the snakes poisonous (not venomous) to predators (such as birds or mammals) that eat the snakes. Since California Newts (Taricha torosa) also contain tetrodotoxin in their skin, and since gartersnake species other than T. sirtalis also eat newts, it is not unreasonable to conclude that any gartersnake that eats either species of newt is poisonous to predators.

Williams, Becky L.; Brodie, Edmund D. Jr.; Brodie, Edmund D. III (2004). "A Resistant Predator and Its Toxic Prey: Persistence of Newt Toxin Leads to Poisonous (Not Venomous) Snakes." Journal of Chemical Ecology. 30 (10): 1901–1919.) https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOEC.0000045585.77875.09

|

| Reproduction |

T. elegans mates primarily in spring.

High altitude populations of this subspecies in California might mate later.

Females are ovoviviparous. After mating with a male they carry the eggs internally until the young are born live.

|

| Habitat |

Occurs in a wide variety of habitats. In California, this snake occurs in coniferous forest, sagebrush, grassy meadows, often in the vicinity of water.

|

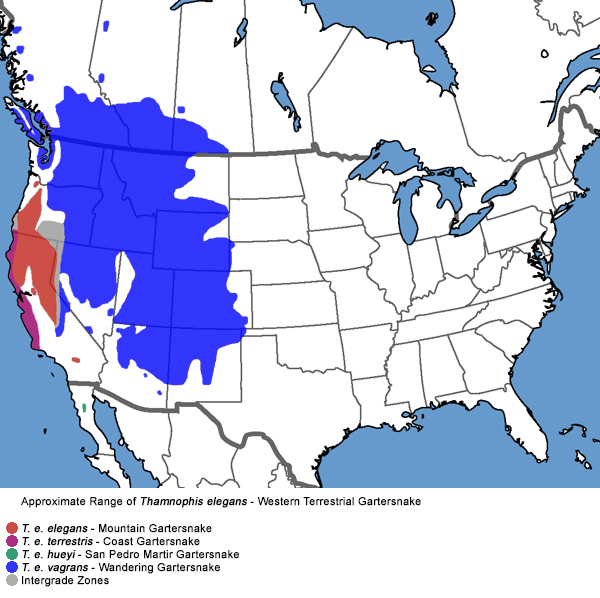

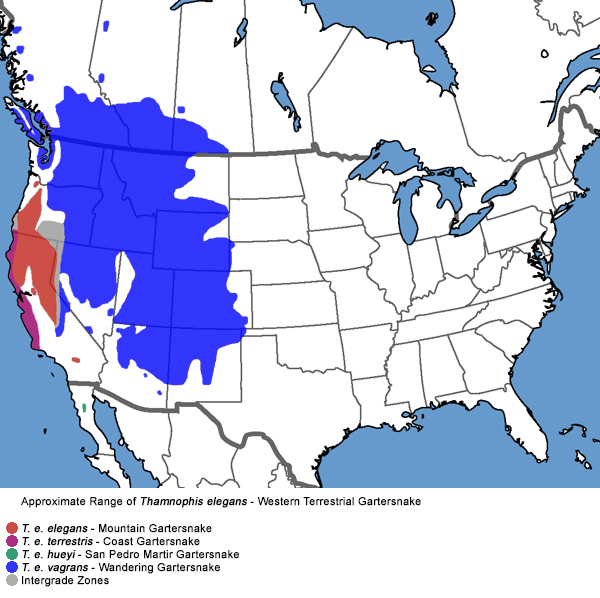

| Geographical Range |

In California, the subspecies Thamnophis elegans vagrans - Wandering Gartersnake, is found east of the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains. Intergrades occur in the far northeast corner of the state in Modoc and Eastern Siskiyou counties and possibly down the eastern side the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Overall, this subspecies has a very large range, occurring from Canada south into New Mexico, including Oregon, Washington, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado, Utah, and Arizona.

The species Thamnophis elegans - Western Terrestrial Gartersnake, ranges widely from the California coast north through most of northern California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Montana, into Canada, including Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan, and east into the states of Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Arizona and New Mexico and just barely making it into South Dakota, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. Many isolated populations exist, including those in the San Bernardino Mountains and one in Baja California Norte, Mexico (the San Pedro Martir Gartersnake.)

|

|

| Elevational Range |

In 2008, Cathryn J. Wise and others showed that the longstanding elevation record of 13,100 ft. (3,990 m) in Colorado for Thamnopis elegans, based on specimens of T. e. vagrans collected in 1960, is questionable, and that a more reliable record for the species is from 12,002 ft. (3658 m) on Humphrey's Peak in Arizona.

(Herpetological Review 39(3), 2008)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

T. e. vagrans intergrades with T. e. elegans in northeast California in Modoc and eastern Siskiyou counties and in south central Oregon (this snake was formerly classified as the subspecies Thamnophis elegans biscutatus - Klamath Gartersnake. Intergrades with T. e. elegans also occur along the southern and southeastern edge of the Sierras.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Three subspecies of Thamnophis elegans are found in California - T. e. vagrans - Wandering Gartersnake, T. e. e.egans - Mountain Gartersnake, and T. e. terrestris - Coast Gartersnake.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Rossman, Ford, and Seigel (1996) emphasize that a detailed study of geographic variation throughout the range of Thamnophis elegans is badly needed.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Bronikowski and Arnold (2001, Copeia 2001:508-513) found several clades within T. elegans that do not always follow the subspecies boundaries.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Hammerson (1999, Amphibians and Reptiles of Colorado. 2nd ed. Univ. of Colorado Press) synonymized T. e. arizonae and T. e. vascotanneri but retained three subspecies, T. e. vagrans, T. e. elegans, and T. e. terrestris.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Using genomic data, Hallas et al. (2021, Journal of Biogeography 48: 2226–2245) confirmed that T. elegans consists of three well-differentiated groups that conform to the three currently recognized subspecies."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Thamnophis elegans vagrans - Wandering Garter Snake (Stebbins 1966, 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Thamnophis elegans vagrans (Stebbins 1954)

Thamnophis ordinoides elegans - Elegant Garter Snake (Eutainia elegans; Eutainia vagrans; Eutaenia infernalis, part; Eutaenia elegans lineolata; Eutaenia elegans brunnea; Eutaenia couchii; Thamnopis infernalis, part; Tropidonotus tri-vittatus; Eutaenia elegans couchii, part; Tropidonotus ordinatus infernalis; Tropidonotus ordinatus ver. couchii; Thamnophis vagrans; Thamnophis parietalis, part; Eutaenia elegans vagrans; Eutaenia hammondi, part; Thamnophis elegans, part; Eutaenia elegans infernalis. Boyd's Garter Snake; Pacific Garter Snake; Wandering Garter Snake; Hammond's Garter Snake; Single-striped Garter Snake; Green Garter Snake;, Western Garter Snake) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Thamnophis elegans vagrans - Wandering Gartersnake (Baird and Girard, 1853)

Western garter snake

(Gray) garter snake

Great basin garter snake

Green garter snake

Large-headed striped snake

Spotted riband snake

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| This species is not known to be threatened, but gartersnakes have been negatively impacted by competition with introduced bullfrogs and non-native fish in some areas. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Colubridae |

Colubrids |

Oppel, 1811 |

| Genus |

Thamnophis |

North American Gartersnakes |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species |

elegans |

Western Terrestrial Gartersnake |

(Baird and Girard, 1853) |

Subspecies

|

vagrans |

Wandering Gartersnake |

(Baird and Girard, 1853) |

|

Original Description |

Thamnophis elegans - (Baird and Girard, 1853) - Cat. N. Amer. Rept., Pt. 1, p. 34

Thamnophis elegans vagrans - (Baird and Girard, 1853) - Cat. N. Amer. Rept., Pt. 1, p. 35

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Thamnophis - Greek - thamnos = shrub or bush + ophis = snake, serpent

elegans - Latin = fine or elegant -- "delicately carinated"

vagrans - Latin = wandering - Yarrow, 1875: "rightly called from its wide range"

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

| Other California Gartersnakes |

T. a. atratus - Santa Cruz Gartersnake

T. a. hydrophilus - Oregon Gartersnake

T. a. zaxanthus - Diablo Range Gartersnake

T. couchii - Sierra Gartersnake

T. gigas - Giant Gartersnake

T. e. elegans - Mountain Gartersnake

T. e. terrestris - Coast Gartersnake

T. hammondii - Two-striped Gartersnake

T. m. marcianus - Marcy's Checkered Gartersnake

T. ordinoides - Northwestern Gartersnake

T. s. fitchi - Valley Gartersnake

T. s. infernalis - California Red-sided Gartersnake

T. s. tetrataenia - San Francisco Gartersnake

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Rossman, Douglas A., Neil B, Ford, & Richard A. Siegel. The Garter Snakes - Evolution and Ecology. University of Oklahoma press, 1996.

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Snakes of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bartlett, R. D. & Alan Tennant. Snakes of North America - Western Region. Gulf Publishing Co., 2000.

Brown, Philip R. A Field Guide to Snakes of California. Gulf Publishing Co., 1997.

Ernst, Carl H., Evelyn M. Ernst, & Robert M. Corker. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2003.

Taylor, Emily. California Snakes and How to Find Them. Heyday, Berkeley, California. 2024.

Wright, Albert Hazen & Anna Allen Wright. Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1957.

Brown et. al. Reptiles of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society,1995.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow,

Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

St. John, Alan D. Reptiles of the Northwest: Alaska to California; Rockies to the Coast. 2nd Edition - Revised & Updated. Lone Pine Publishing, 2021.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This snake is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

Dark Blue: Range of this subspecies in California

Dark Blue: Range of this subspecies in California