Red

Red: Pacific Hawksbill Sea Turtles are occasionally

seen off the southern California coast in this area

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

|

| |

|

|

| |

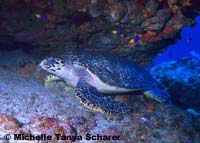

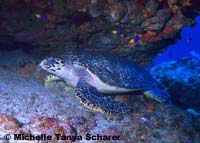

Adult, near Kona, Island of Hawai'i

© Anonymous |

|

|

|

|

| Stuffed and mounted Adult, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History |

Skeleton,

National Museum of Natural History |

Habitat in California - the Pacific Ocean

|

| |

|

|

| Atlantic Hawksbill Sea Turtle - Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata |

| Below are pictures of the Atlantic Hawksbill, which is similar in appearance to the Pacific Hawksbill, the subspecies which occurs in California. |

|

|

|

Captive rescued juvenile from the Gulf of Mexico. Sea Turtle Rescue Center, Sea Turtle Inc., South Padre Island, Texas.

|

|

|

|

| Close-up of shell of captive juvenile shown above. |

Adult, Puerto Rico,

© Michelle Tanya Scharer.

|

Hawk-shaped bill |

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 18 - 36 inches in shell length (46 - 91 cm) and 30 - 280 lbs. (Stebbins 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A small to medium-sized sea turtle with paddle-like limbs, a heart-shaped carapace with a central keel and a serrated rear edge.

The shields overlap like shingles, except in hatchlings and very old animals.

There are two pairs of prefrontal scales, and 4 costal shields on each side of the carapace.

The first costal shield does not touch the nuchal.

A long, narrow, sharp snout, like that of a hawk, gives this turtle its common name, Hawksbill. |

| Color and Pattern |

| Color is a dark greenish brown with a marbled or radiating pattern. The plastron is yellow and hinge-less. The head scales are black to chestnut brown in the center, with lighter margins. The chin and throat are yellow. |

| Male / Female Differences |

Males have a long tail that extends well past the edge of the shell and a curved nail on the front of each flipper.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Not much is known about Hawksbill behavior due to their solitary habits.

They are apparently diurnal, becoming nocturnal when nesting.

Hawksbills sleep at night on the bottom, surfacing occasionally for air.

They will readily bite to defend themselves.

Hawksbills are possibly the least migratory of sea turtles, but some tagged individuals have been recorded traveling long distances.

As with other sea turtles, the yearly activity during the breeding year of a Hawksbill includes a long period of foraging, migration to nesting beach, nesting, and migration back to the feeding grounds.

|

| Diet and Feeding |

| Omnivorous. Feeds upon many invertebrates, preferring sponges (including toxic sponges) in some areas, mollusks, jellyfish, corals, sea anemones, sea urchins, crabs, rock lobster, fish, algae, sea grasses, and mangroves. |

| Reproduction |

Hawksbills mate in shallow water off the nesting beach and nest individually, not in large groups like other sea turtles. In the Pacific, nesting has been observed in Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Mexico, and Hawaii.

Females nest every 2 - 3 years between August and November at an average of 4 - 5 times per season. Sheltered, short, steep sandy beaches are preferred, and nests are often dug in the sandy soil among vegetation instead of open sand.

A female Hawksbill emerges from the ocean at night and crawls onto the nesting beach, using all four limbs to rapidly walk over the sand, instead of using just the two forelimbs to pull herself as other sea turtles do. She scrapes out a shallow body pit, then digs a nest and lays a clutch of 50 - 200+ eggs. Her total time on the beach is 1 - 2 hours. Nests are robbed by humans, and other mammals such as dogs, raccoons, and rats. The eggs hatch in 60 - 70 days and hatchlings emerge in the morning or in the evening and begin a frantic crawl towards the water. Hatchlings trying to get to the sea are eaten by birds, crabs, and other predators, and again by fish, octopus, sharks, and others once they reach the water.

Sea Turtle Navigation

A study published in 2018 * shows that Loggerhead Sea Turtles use the earth's magnetic fields to navigate back to within about 50 miles of where they were born. They learn the magnetic signature of their natal beach through geomagnetic imprinting.

* J. Roger Brothers, Kenneth J. Lohmann. Evidence that Magnetic Navigation and Geomagnetic Imprinting Shape Spatial Genetic Variation in Sea Turtles. Current Biology Volume 28, Issue 8, 23 April 2018.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits shallow coastal waters in rocky places, coral reefs, mangrove-bordered bays, estuaries, and mud-bottomed lagoons. Sometimes found in deep water. Juveniles float on currents with patches of Sargassum weed.

|

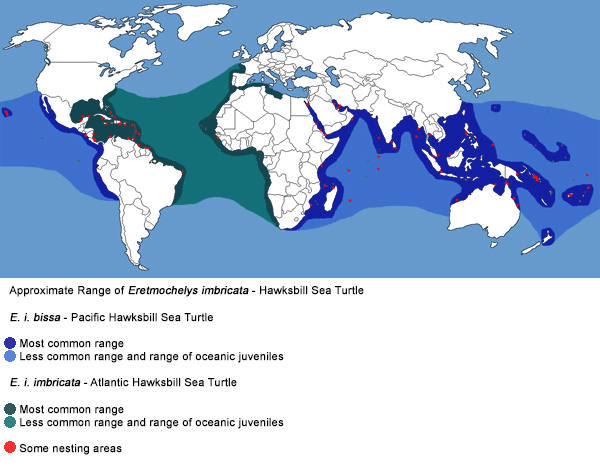

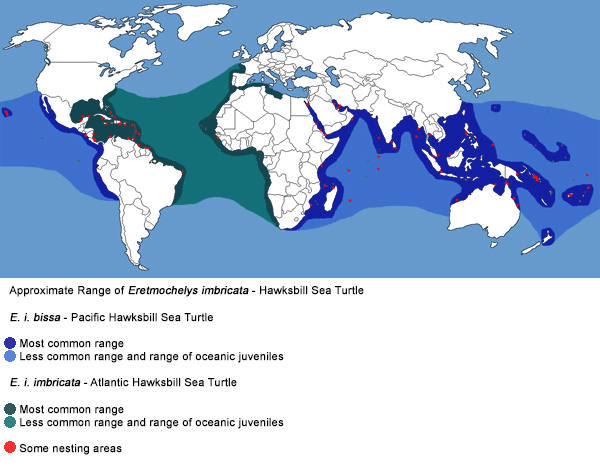

| Geographical Range |

The Hawksbill species is found in the warmer parts of the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans. In the eastern Pacific, it is found from southern California to Peru. It is found infrequently in the Mediterranean Sea.

The subspecies found in our area E. i. bissa, the Pacific Hawksbill, is found in the tropical parts of the Indian and Pacific oceans, from Madagascar to the Red Sea, east to Australia, Japan and the Hawaiian Islands, and in the eastern Pacific from Peru to Baja California. Stragglers occasionally stray north to Southern California waters, probably during El Niño years when ocean temperatures rise.

Sea turtles can show up almost anywhere on the coast of California, but most sightings are not documented.

I have not yet found any records of sightings of Pacific Hawksbill Sea Turtles in California waters. The only museum specimen from California I can find is from the Utah Museum of Natural History which is labelled as coming from the Hermosa Reptile and Wild Animal Farm, Hermosa Beach. There is no indication that the specimen was collected in California, but it probably was. Sources such as California's endangered animals list, Robert Stebbins' 2003 and 2012 field guides, and Ernst, Lovich, and Barbur (1994) state that this species has been seen in Southern California waters.

|

Click Map to Enlarge

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Two subspecies are recognized - Eretmochelys imbricata bissa - Pacific Hawksbill, and Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata - Atlantic Hawksbill.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Eretmochelys Fitzinger, 1843—Hawksbill Sea Turtles

"Hedges et al. (2019, Caribbean Herpetology (67): 1-53) used the English name to "Hawksbill Seaturtle(s)" for all members of this genus. We have followed the traditional English name usage of Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (2021, Chelonian Research Monographs (8): 1–472)."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

E. imbricata (Linnaeus, 1766)—Hawksbill Sea Turtle

"Bowen and Karl (2007, Molecular Ecology 16: 4886–4907) reviewed population genetics and phylogeography of marine turtles and while they noted mtDNA divergence between Indo-Pacific and Atlantic Eretmochelys imbricata, they recognized no taxa below the species level. Gaos et al. (2016, Ecology and Evolution 6: 1251–1264) suggested that Eastern Pacific E. imbricata are more closely related to those from the Indo-Pacific than those in the Atlantic. However, they made no taxonomic recommendations affecting the currently recognized subspecies. Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (2021, Chelonian Research Monographs (8): 1–472) recognized no subspecies, treating E. i. bissa (Rüppell, 1835) as a synonym of E. imbricata."

(Nicholson, K.

E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Eretmochelys imbricata - Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Eretmochelys imbricata - Hawksbill (Stebbins 2003)

Eretmochelys imbricata bissa - Pacific Hawksbill (Stebbins 1985)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

Endangered.

Getting accurate estimates of Hawksbill population numbers is difficult due to their behavior of nesting individually on scattered beaches. This behavior also makes assisting their reproductive success with nesting preserves ineffective.

Hawksbills have been in demand for their meat, their eggs and the translucent scutes of their shell, from which "tortoiseshell" products are made. They also suffer mortality through entanglement in fishing lines and nets, oil spills, and possibly from the development and degradation of nesting beaches, which is a worldwide problem with other species of sea turtles.

Other causes for the decline of sea turtles include the degradation of feeding habitats, ingestion of plastic garbage, especially plastic grocery bags (which look like jellyfish floating on the surface) and offshore boats moving so quickly that turtles are not able to move out of the way fast enought to avoid being killed or injured. Some authorities also question whether humans handling nesting females and doing research on nesting beaches is stressing the turtles and lowering reproduction and survivorship.

Increased warming due to global climate change might be creating too many female sea turtles.

The sex of a sea turtle is determined by the temperature of the egg when it is incubating buried in the sand. Warmer temperatures produce a higher number of females. Jensen et al * found that the increase in temperature caused by global climate change is making the sex of most of the Green Sea Turtles they studied female, including over 99% of all juveniles and subadults. It is not known how few males are required to sustain sea turtle populations. A lack of a sufficient number of males to perpetuate a population could eventually be catastrophic.

* Michael P. Jensen, Camryn D. Allen, Tomoharu Eguchi, Ian P. Bell, Erin L. LaCasella, William A. Hilton, Christine A.M. Hof, Peter H. Dutton. Environmental Warming and Feminization of One of the Largest Sea Turtle Populations in the World. Current Biology Volume 28, Issue 1, 8 January 2018.

National Geographic article, 8 January 2018. |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Cheloniidae |

Sea Turtles |

Oppel, 1811 |

| Genus |

Eretmochelys |

Hawksbill Sea Turtles |

Fitzinger 1843 |

| Species |

imbricata |

Hawksbill Sea Turtle |

(Linnaeus, 1766) |

Subspecies

|

bissa |

Pacific Hawksbill Sea Turtle |

(Rüppell, 1835) |

|

Original Description |

Eretmochelys imbricata - (Linnaeus, 1766) - Syst. Nat., 12th ed., Vol. 1, p. 350

Eretmochelys imbricata bissa -(Ruppell, 1835) - Neue Wirbelthiere zu de Fauna Von Abyssinien Gehorig, Vol. 3 , Amph., p. 4, pl. 2

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Eretmochelys - Greek - eretmo = oar + chelys = turtle - refers to the shape of the forelimb

imbricata - Latin = overlapping - probably refers to the scute pattern

bissa - Latin - bis = double, twice + -sa = refers to the concept of bissa as a second species of Caretta

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Turtles |

C. caretta - Loggerhead Sea Turtle

C. mydas - Green Sea Turtle

L. olivacea - Olive Ridley Sea Turtle

D. coriacea - Leatherback Sea Turtle

|

|

More Information and References |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - Hawksbill Sea Turtle

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

USFWS

Turtles.org

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Carr, Archie. Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Cornell University Press, 1969.

Ernst, Carl H., Roger W. Barbour, & Jeffrey E. Lovich. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution 1994.

(2nd Edition published 2009)

Range and Nesting Information has been adapted from a number of sources, including:

Sea Turtle Conservancy

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Wikipedia

Witherington, Blair E. Sea Turtles: An Extraordinary Natural History of Some Uncommon Turtles. Voyageur Press, 2006.

Spotila, James R. Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to Their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. The Johns Hopkins University Press and Oakwood Arts, 2004.

Perrine, Doug. Sea Turtles of the World. Voyageur Press, Inc., 2003.

Arnold, E. Nicholas, and Denys W. Ovenden. Reptiles and Amphibians of Europe. Princeton University Press and Oxford, 2002.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This turtle is not included on the Special Animals List, maybe because it is not considered a species that occurs in California. It is considered to be critically endangered by the World Conservation Union.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

|

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

|

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

|

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

|

|

| USDA Forest Service |

|

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|