|

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Monterey Bay © James Maughn |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Adult, Monterey Bay © James Maughn |

|

As with the turtle James Maughn saw in the photos above, many of the sightings of Leatherbacks in California waters occur from whale-watching or pelagic birding boats, where the occupants are carefully scanning the water for wildlife. Below are links to more pictures of Leatherbacks taken from boats off the California coast.

|

| Shearwater Journeys |

Monterey Bay |

Don Roberson |

| |

|

|

| Leatherbacks from outside California |

|

|

|

Adult female laying eggs on the beach and turtle researchers,

Guanacaste, Costa Rica. © William Flaxington. |

Adult female, covering her eggs, French Guiana. © 2002 Matthew Godfrey |

|

|

|

| Hatchling, © 2002 Chris Johnson |

Leatherback tracks on beach, Guanacaste, Costa Rica.

© William Flaxington. |

Habitat - the Pacific Ocean, San Mateo County, in the general area where a Leatherback was observed. |

| |

|

|

| |

Skeleton,

National Museum of Natural History |

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

The largest turtle on Earth, growing to the size of a small automobile.

Adults average 48 - 96 inches in shell length (122 - 244 cm). 600 - 1,600 lbs, possibly as much as a ton. (Stebbins 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A huge marine turtle with smooth leathery skin, a large head, paddle-like clawless limbs, no scales or claws, and an elongated, triangular carapace with 7 prominent lengthwise keels that lacks a rigid shell of horny scutes.

Many small bony platelets embedded in the skin make up the carapace which is not connected to the ribs or the backbone. |

| Color and Pattern |

| Color is dark brown, slate, or blue-black and either unmarked or with pale blotches. The skin on the head, neck, and limbs is black or dark brown with some white spotting. The plastron is gray or black, with 5 ridges |

| Male / Female Differences |

Males have a tail that is longer than the hind limbs, and a concave plastron.

Females tend to have a lot of pink on the head. |

| Young |

Young have many small scales, a rudder-like tail, and a thin, high dorsal keel. Their flippers are edged with white.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Leatherback Sea Turtles are an ancient lineage over 70 million years old that outlived the mass extinction that killed the dinosaurs. Little is known about their behavior in the wild. They are sometimes found in large groups, especially around large schools of jellyfish.

Leatherbacks are capable of diving to great depths on one breath. They are also capable of swimming and feeding in cold waters due to their ability to keep their internal temperature higher than the ambient temperature.

Leatherbacks are thoroughly aquatic and very powerful swimmers, often swimming great distances far out to sea as they follow drifting flotillas of jellyfish.

*Research since 2001 has discovered that the Leatherbacks found on the west coast of North America are part of the genetic stock as those that nest in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. The Central Coast of California, including Monterey Bay, is one stop in the seasonal migration of Leatherbacks in the Pacific as they travel across the ocean from the western Pacific to feed on jellyfish, especially brown sea nettles. Scott Benson, marine ecologist for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration at the Southwest Fisheries Science Center, has captured, tagged, and released leatherbacks in Monterey Bay and Indonesia and tracked them as they cross the ocean. He discovered that they arrive in California waters in June where they stay until mid October when they move to waters off Hawaii. They return to California the following summer, and they may repeat this journey two or three times before they are ready to swim all the way to the nesting beaches in Indonesia.

*(Source: Lily Dayton, Monterey County Herald, 7/19/2009.) |

| Diet and Feeding |

Carnivorous, eating mainly jellyfish, but also consuming some plant matter such as kelp and algae and other invertebrates and vertebrates, including sea urchins, snails, octopi, squid, crabs, and small fish.

Feeds on the surface and below. |

| Reproduction |

Leatherbacks breed in the open ocean, but where exactly is not known. It may occur off the nesting beaches after migration, or it may occur before or during migration.

Nesting along the Pacific coast takes place usually from September through March, most frequently in November and December. The main nesting beaches in the Pacific are Mexico, Costa Rica, and Indonesia, but most Leatherbacks found in California waters come from beaches in Indonesia. In the United States, nesting occurs on beaches in Florida and Georgia, and formerly in Texas.

Females return to a preferred nesting beach, most likely the beach from which they hatched. An individual female breeds every 2 - 3 years. Nesting beaches are sandy with a gradual slope and a deep water approach so the turtles can ride the waves high onto the beach.

A female leatherback climbs onto the nesting beach at night where she digs a deep nest with their hind feet and lays a clutch of 50 - 166 eggs (averaging 60 - 66 in the eastern Pacific) many of which are not viable, having no yolk. An average of 6 clutches per season is probably normal for a breeding female. She will return to the beach every 8 - 12 days to lay another clutch of eggs.

Egg mortality is high due to predation by humans and other animals. The eggs hatch in 60 - 65 days. Many young never reach the water due to attacks by predators, or they succumb to aquatic predators after they enter the water. Hatchlings emerge at night where they sometimes circle to get their bearings, then crawl quickly to the ocean where they swim continuously for the first day. After the young enter the ocean they are seldom seen along the coast.

Sea Turtle Navigation

A study published in 2018 * shows that Loggerhead Sea Turtles use the earth's magnetic fields to navigate back to within about 50 miles of where they were born. They learn the magnetic signature of their natal beach through geomagnetic imprinting.

* J. Roger Brothers, Kenneth J. Lohmann. Evidence that Magnetic Navigation and Geomagnetic Imprinting Shape Spatial Genetic Variation in Sea Turtles. Current Biology Volume 28, Issue 8, 23 April 2018.

|

| Habitat |

Pelagic, living in the open ocean and occasionally entering the shallower water of bays and estuaries.

|

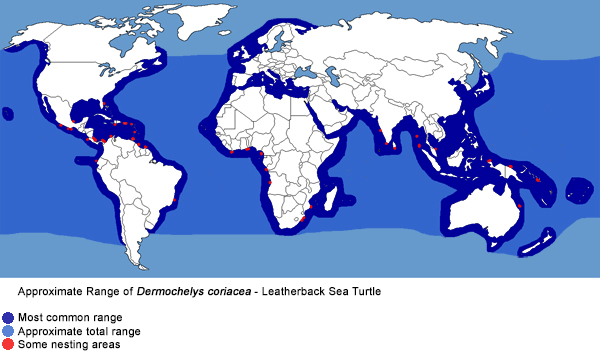

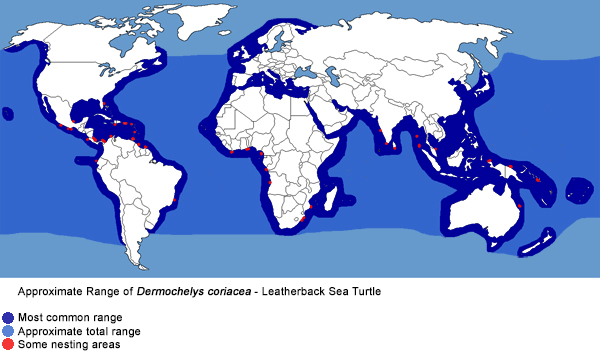

| Geographical Range |

The Leatherback is the most widely-distributed sea turtle in the world. Found mostly in tropical waters, they move into temperate waters during the summer. They have been recorded from cold waters in Norway, Iceland, and Alaska.

Sea turtles can show up almost anywhere on the coast of California, but most sightings are not documented. The locations mentioned here only represent a small percentage of sightings. Most sightings in California occur from boats out at sea. Locations where Leatherbacks have been observed in California include north of Del Mar, San Diego County, off San Clemente and Santa Rosa islands, north of Jalama Beach and south of Santa Barbara Harbor, Santa Barbara County, the mouth of the Ventura River and a mile east of Emma Wood State Beach in Ventura County, Monterey Bay, Monterey County, Cayucos, San Luis Obispo County, the north end of Pigeon Pt. Beach in San Mateo County, southeast of Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz County, and Pt. Reyes and Bolinas, in Marin County.

Also "There is a Pacific Leatherback Turtle record for Pebble Beach, Crescent City ca. 1981 at the Cal Poly Humboldt State University Natural History Museum, Arcata, CA Campus, washed up on beach in December cold storm." (Bradford R. Norman)

|

Click Map to Enlarge

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Two subspecies have been described -

Dermochelys coriacea schlegelii - Pacific Leatherback, and

Dermochelys coriacea coriacea - Atlantic Leatherback.

A third subspecies that occurs off the west coast of the Americas has also been suggested, but these races are so poorly differentiated that they are no longer accepted by many herpetologists.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dermochelys Blainville, 1816—Leatherback Sea Turtles

"Hedges et al. (2019, Caribbean Herpetology (67): 1-53) used the English name to "Leatherback Seaturtle(s)" for all members of this genus. We have followed the traditional English name usage of Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (2021, Chelonian Research Monographs (8): 1–472)."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

D. coriacea (Vandelli, 1761)—Leatherback Sea Turtle

"Molfetti et al. (2013, PLoS One 8: e58061) and Dutton et al. (2013, Conservation Genetics 14: 625–636) demonstrated genetic structure within Dermochelys coriacea in the Atlantic Ocean. They made no taxonomic recommendations."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Dermochelys coriacea - Leatherback Sea Turtle (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Dermochelys coriacea schlegeli - Pacific Leatherback (Stebbins 1966, 1985, 2003)

Dermochelys coriacea - Leather-backed Turtle (Stebbins 1954)

Dermochelys schlegelii - Pacific Leatherback Turtle (Sphargis schlegelii) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Luth

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

Critically endangered. Undergoing a rapid decline.

Some reasons for the decline include harvesting of their eggs, degradation of nesting beaches primarily through coastal development, mortality from longline, drift, and set gill-net fishing (bycatch) and discarded fishing nets. Mortality from the accidental consumption of floating plastic bags and balloons which resemble their preferred jellyfish prey is another problem. The indigestible plastic blocks the gastrointestinal tract eventually killing the turtle. (Think about that next time you consider buying and releasing a large balloon or using plastic shopping bags!) Offshore boat traffic is also a serious threat when the boats move so quickly that the turtles cannot swim out of their way in time to avoid collision.

Leatherback eggs are widely consumed, but the flesh is not generally eaten. The flesh can store toxins from jellyfish and become poisonous. Human deaths have been reported after consumption of Leatherback meat.

A 2012 study of leatherback migration led by Helen Bailey of the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science found that Pacific Ocean leatherbacks have to move faster and expend more energy to find food than Atlantic Ocean leatherbacks, most likely due to climate change patterns in the Pacific such as El Nino which create temperature variations in the ocean that make it hard for the turtles to find reliable sources of food, especially jellyfish, their main food source. This could be why the Atlantic population is stable but the Pacific population is seriously threatened.

Leatherbacks are listed as Critically Endangered globally by the IUCN. According to the February 2013 study by Tapilatu et al cited below, although some Leatherback nesting populations in the Atlantic have been increasing recently, Pacific populations have declined by over 95 percent since 1980. 75 percent of Leatherbacks in the Western Pacific nest at Bird's Head Peninsula, Papua Barat, Indonesia, on two beaches - Jamursba Medi, and Wermon Beach. The estimated annual number of nests at Jamursba Medi has declined 78.3 percent since 1984. The estimated annual number of nests at Wermon Beach has declined 62.8 percent since 2002. Collectively, this is a rate of decline of 5.9 percent per year since 1989. If this rate of decline continues, the species could be extinct in as little as 20 years.

Increased warming due to global climate change might be creating too many female sea turtles.

The sex of a sea turtle is determined by the temperature of the egg when it is incubating buried in the sand. Warmer temperatures produce a higher number of females. Jensen et al * found that the increase in temperature caused by global climate change is making the sex of most of the Green Sea Turtles they studied female, including over 99% of all juveniles and subadults. It is not known how few males are required to sustain sea turtle populations. A lack of a sufficient number of males to perpetuate a population could eventually be catastrophic.

* Michael P. Jensen, Camryn D. Allen, Tomoharu Eguchi, Ian P. Bell, Erin L. LaCasella, William A. Hilton, Christine A.M. Hof, Peter H. Dutton. Environmental Warming and Feminization of One of the Largest Sea Turtle Populations in the World. Current Biology Volume 28, Issue 1, 8 January 2018.

National Geographic article, 8 January 2018.

|

| Official California State Marine Reptile |

Established as the state marine reptile in 2012.

October 15 was designated as Pacific Leatherback Sea Turtle Conservation Day.

On that day, millions of Californians celebrate with fireworks, dancing, picnics and - - - wait, they don't?

But they will some day, I'm sure of it.

|

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Dermochelyidae |

Leatherback Sea Turtles |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Genus |

Dermochelys |

Leatherback Sea Turtle |

Blainville, 1816 |

Species

|

coriacea |

Leatherback Sea Turtle |

(Vandelli, 1761) |

|

Original Description |

Dermochelys coriacea - (Vandelli, 1761) - Epistola de Holothurio, et Testudine coriacea ad celeberrimum Carolum Linnaeum Equitum Naturae Curiosum Dioscorcidem II. Conzatti, Patavii (Padova). 12 pp.

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Dermochelys - Greek - derma = skin + chelys = turtle - refers to soft skin covering the shell

coriacea - Latin - corium = leather + -acea = having the nature or color of - refers to the leathery carapace

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Turtles |

C. caretta - Loggerhead Sea Turtle

C. mydas - Green Sea Turtle

E. i. bissa - Pacific Hawksbill Sea Turtle

L. olivacea - Olive Ridley Sea Turtle

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - Leatherback Sea Turtle

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Carr, Archie. Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Cornell University Press, 1969.

Ernst, Carl H., Roger W. Barbour, & Jeffrey E. Lovich. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution 1994.

(2nd Edition published 2009)

Lemm, Jeffrey. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of the San Diego Region (California Natural History Guides). University of California Press, 2006.

Tapilatu, R. F., P. H. Dutton, M. Tiwari, T. Wibbels, H. V. Ferdinandus, W. G. Iwanggin, and B. H. Nugroho. 2013. Long-term decline of the western Pacific leatherback, Dermochelys coriacea: a globally important sea turtle population. Ecosphere 4(2):25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1890/ES12-00348.1

Range and Nesting Information has been adapted from a number of sources, including:

Sea Turtle Conservancy

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Wikipedia

Witherington, Blair E. Sea Turtles: An Extraordinary Natural History of Some Uncommon Turtles. Voyageur Press, 2006.

Spotila, James R. Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to Their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. The Johns Hopkins University Press and Oakwood Arts, 2004.

Perrine, Doug. Sea Turtles of the World. Voyageur Press, Inc., 2003.

Arnold, E. Nicholas, and Denys W. Ovenden. Reptiles and Amphibians of Europe. Princeton University Press and Oxford, 2002.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

FE |

Endangered - 6/02/1970 |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

SCE |

Candidate for Endangered Listing 8/25/2020 |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|