|

|

|

|

| Captive rescued adult from the Gulf of Mexico at Sea Turtle Rescue Center, Sea Turtle Inc., South Padre Island, Texas |

|

|

|

| Adult underwater, Brooklyn Aquarium, New York |

|

|

|

| Adult, Greece © Johan Chevalier |

Adult © Carlos Rodriguez Munoz

|

Habitat in California - the Pacific Ocean |

| |

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

The largest hard-shelled turtle on earth.

Adults are generally 33.5 - 39 inches in shell length (85 - 100 cm) and weigh around 300 lbs. (135 kg).

The maximum known length is 7 ft. (213 cm), and turtles weighing 1,000 lbs. (453 kg.) have been reported.

(These are old records and turtles of this size probably no longer exist.)

In our area, most Loggerheads are around 8 - 36 inches in shell length (20.3 - 91 cm). (Stebbins 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A large marine turtle with a very broad head, a thick, bony, elongated heart-shaped shell, and huge paddle-like limbs.

The carapace is high in front, and contains 5 or more costal shields on each side which do not overlap.

The posterior rim is serrated.

The first shield touches the nuchal shield.

There are 2 pairs of pre-frontal scales. |

| Color and Pattern |

| The carapace is reddish or orange-brown, with yellow edging around the shields. The plastron is cream colored with some dusky clouding. The head pigmentation varies from reddish to olive brown, with many yellow-bordered scales. The flippers are rusty brown. |

| Male / Female Differences |

| Males have a wider shell, a long tail that extends well beyond the edge of the shell, a recurved claw on each forelimb, and more yellow color on the head. |

| Young |

Young have a yellowish carapace with 3 lengthwise keels.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Aquatic, sometimes found far out in the open ocean. Hatchlings float and cannot sink. Hatchlings and juveniles are usually found drifting with ocean currents and eddies associated with drifting mats of marine vegetation.

Loggerheads spend much time floating on the surface sleeping and basking, but also rest submerged on the bottom.

During a year when she reproduces, the activity of a female Loggerhead can be divided into four periods - foraging (most of the year), migration to the nesting area, nesting, and migration back to the feeding range. In other years she will probably spend all year foraging in her feeding range.

Females usually return to the beach where they were hatched to nest several times during their lives, often traveling over a thousand miles to get there. How they manage to navigate such long distances to such a specific area is a mystery. This navigation might involve a combination of light cues, sound, smell, and an ability to detect the earth's magnetic fields. |

| Diet and Feeding |

| Omnivorous. Invertebrates are the most important food group for Loggerheads. Their large head and massive jaws are adapted for crushing hard-shelled prey. Loggerheads eat sponges, crustaceans, mollusks, jellyfish, worms, cephalopods, bivalves, barnacles, shrimp, fish, and marine plants. |

| Reproduction |

Adults are sexually mature at between 10 and 30 years of age.

Females have been recorded

reproducing for at least 36 years. (Shamblin, et al,

Herpetological Review 52(1), 2021)

Unlike all other marine turtles, Loggerheads nest on beaches mostly outside of the tropics. Nesting locations include Mexico, Brazil, Japan, South Africa, Oman, Australia, and the southeastern United States, from New Jersey to Texas, mostly in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Nesting occurs generally from May to August. The average female nests every 2 or 3 years, and sometimes up to 7 years. Females nest from 1 - 7 times per season (usually 1 - 3). Egg clutches are laid at intervals of around 11 - 15 days, in-between which a female may swim to reefs or estuaries to feed.

Most nests are dug at night, but diurnal nesting does occur. Wide beaches with a moderately-steep slope are preferred. The female Loggerhead crawls onto the beach then wanders around to find a proper nesting location. Then she digs the nest, lays around 125 eggs, then crawls back into the water. The whole process takes an hour or two.

Eggs are subject to predation by many animals, including crabs, crows, armadillos, raccoons, dogs, cats, skunks, snakes, and humans. The eggs hatch in 46 - 80 days. Hatchlings emerge at night and crawl frantically to the sea, dodging many predators which are waiting to eat them, which can include crows, snakes, crabs, vultures, seabirds, raccoons and dogs.

Sea Turtle Navigation

A study published in 2018 * shows that Loggerhead Sea Turtles use the earth's magnetic fields to navigate back to within about 50 miles of where they were born. They learn the magnetic signature of their natal beach through geomagnetic imprinting.

* J. Roger Brothers, Kenneth J. Lohmann. Evidence that Magnetic Navigation and Geomagnetic Imprinting Shape Spatial Genetic Variation in Sea Turtles. Current Biology Volume 28, Issue 8, 23 April 2018.

|

| Habitat |

Pelagic, living in the open ocean and rarely coming onto land.

Enters coastal bays, lagoons, salt marshes, estuaries, creeks, and the mouths of large rivers.

|

| Geographical Range |

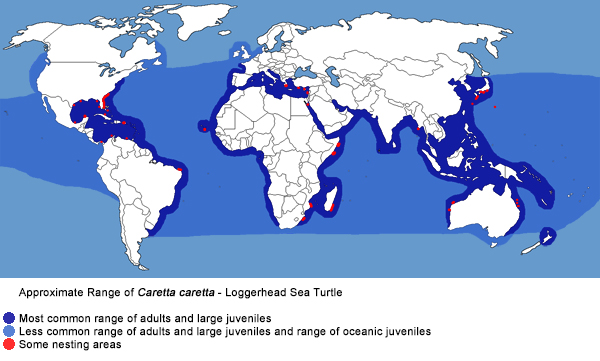

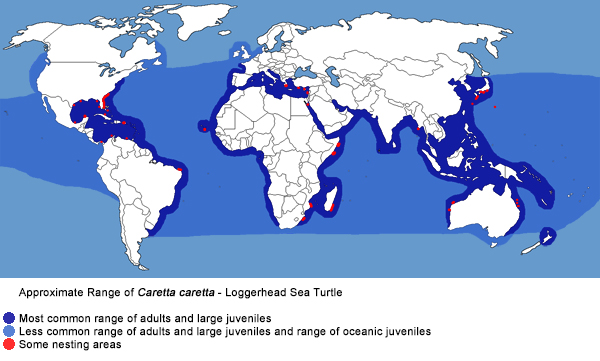

Loggerheads are found throughout temperate regions around the world in the Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic oceans, and the Mediterranean and Caribbean seas, most commonly between latitudes 40 degrees north and south.

On the Pacific coast they are found from near Santa Cruz Island south to Chile. They are occasionally seen farther north.

Sea turtles can show up almost anywhere on the coast of California, but most sightings are not documented. The locations mentioned here only represent a small percentage of sightings. California sightings are rare. Most are juveniles that have crossed Pacific Ocean after hatching on beaches in Japan (Stebbins 2003). Sightings tend to occur from July to September and but may occur much of the year during El Niño years when ocean temperatures rise. Locations where Loggerheads have been seen in California waters include deep water off Newport in Orange County, several locations off San Clemente Island, near Paradise Cove at Malibu in Los Angeles County, False Cape in Humboldt County, south of West Anacapa Island, Santa Barbara, Montecito and Jalama Beach in Santa Barbara County, and San Diego and Camp Pendleton in San Diego County.

|

Click Map to Enlarge

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Two subspecies were once recognized - Caretta caretta caretta - Atlantic Loggerhead, and

Caretta caretta gigas - Pacific Loggerhead, but these subspecies are now considered invalid.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Caretta Rafinesque, 1814—Loggerhead Sea Turtles

"Hedges et al. (2019, Caribbean Herpetology (67): 1-53) used the English name "Loggerhead Seaturtle(s)" for all members of this genus. We have followed the traditional English name usage of Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (2021, Chelonian Research Monographs (8): 1–472). "

"Shamblin et al. (2014, PLoS One 9: e85956), using samples from 42 nesting rookeries, identified 59 different mitochondrial haplotypes. They made no taxonomic recommendations."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Caretta caretta - Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Caretta caretta - Loggerhead (Stebbins 2003)

Caretta caretta gigas - Pacific Loggerhead (Stebbins 1966, 1985)

Caretta caretta - Loggerhead Turtle (Stebbins 1954)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

Endangered.

The most populous sea turtle in North American waters, but their numbers are declining.

Development and degradation of beaches and coastal islands has destroyed nesting beaches or interfered with nesting activities. Artificial lights on beaches may cause females to return to the ocean without laying eggs. Hatchlings disoriented by the lights sometimes crawl toward highways and get run over. Nesting success is decreased due an increase in nest predators such as raccoons which thrive in response to human development. Adults sometimes drown in shrimp nets or get killed by boat traffic. Floating plastic bags and balloons which resemble jellyfish are also a problem. When eaten, they block the gastrointestinal tract eventually killing the turtle. Entanglement in discarded fishing nets is also a serious threat.

Increased warming due to global climate change might be creating too many female sea turtles.

The sex of a sea turtle is determined by the temperature of the egg when it is incubating buried in the sand. Warmer temperatures produce a higher number of females. Jensen et al * found that the increase in temperature caused by global climate change is making the sex of most of the Green Sea Turtles they studied female, including over 99% of all juveniles and subadults. It is not known how few males are required to sustain sea turtle populations. A lack of a sufficient number of males to perpetuate a population could eventually be catastrophic.

* Michael P. Jensen, Camryn D. Allen, Tomoharu Eguchi, Ian P. Bell, Erin L. LaCasella, William A. Hilton, Christine A.M. Hof, Peter H. Dutton. Environmental Warming and Feminization of One of the Largest Sea Turtle Populations in the World. Current Biology Volume 28, Issue 1, 8 January 2018.

National Geographic article, 8 January 2018. |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Cheloniidae |

Sea Turtles |

Oppel, 1811 |

| Genus |

Caretta |

Loggerhead Sea Turtles |

Rafinesque, 1814 |

Species

|

caretta |

Loggerhead Sea Turtle |

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

|

Original Description |

Caretta caretta - (Linnaeus, 1758) - Syst. Nat., 10th ed., Vol. 1, p. 197

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Caretta - Spanish - carey = type of turtle + Latin -etta = little

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Turtles |

C. mydas - Green Sea Turtle

E. i. bissa - Pacific Hawksbill Sea Turtle

L. olivacea - Olive Ridley Sea Turtle

D. coriacea - Leatherback Sea Turtle

|

|

More Information and References |

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration - Loggerhead Sea Turtle

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Turtles.org

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Carr, Archie. Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Cornell University Press, 1969.

Ernst, Carl H., Roger W. Barbour, & Jeffrey E. Lovich. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution 1994.

(2nd Edition published 2009)

Lemm, Jeffrey. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of the San Diego Region (California Natural History Guides). University of California Press, 2006.

Range and Nesting Information has been adapted from a number of sources, including:

Sea Turtle Conservancy

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Wikipedia

Witherington, Blair E. Sea Turtles: An Extraordinary Natural History of Some Uncommon Turtles. Voyageur Press, 2006.

Spotila, James R. Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to Their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. The Johns Hopkins University Press and Oakwood Arts, 2004.

Perrine, Doug. Sea Turtles of the World. Voyageur Press, Inc., 2003.

Arnold, E. Nicholas, and Denys W. Ovenden. Reptiles and Amphibians of Europe. Princeton University Press and Oxford, 2002.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

None |

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

None |

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

FE

FT |

Endangered 10/24/2011

Threatened

7/28/1978

The 1978 listing was for the worldwide range of the species. The 10/24/2011 final rule is for the North Pacific DPS (north of the equator & south of 60 degrees north latitude).

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

None |

|

|

|