|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Kern County |

Adult, Kern County |

Adult, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Kingston Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Keith Condon |

Breeding adult male, Kings County

© Patrick Briggs |

Breeding adult male, Kern County

© Ryan Sikola |

Adult, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

| |

Young adult, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

|

Adult, Tulare County

© Jonathan Hakkim |

This striped adult was found in the Kingston Mountains of northeastern San Bernardino County. The side stripes extend far onto the tail as they do on a

Northwestern Skink. © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

Toothy Skinks, genus Plestiodon, have smooth shiny cycloid scales that are reinforced with bone. Plestiodon skiltonianus is shown here.

|

| |

|

|

|

| Skinks From Intergrade Areas |

|

|

|

|

| Intergrade with P. g. cancellosus, Monterey County |

Intergrade with P. g. cancellosus, Monterey County |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile, Kern County |

Juvenile, Kern County

© Brad Alexander |

Juvenile, Kern County © Kevin Shayer |

Juvenile, Granite Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Keith Condon |

|

|

|

|

| |

Tiny juvenile missing its tail, Kern County |

|

Juvenile, Kingston Mountains, San Bernardino County. © Keith Condon |

|

|

|

|

| Sub-adult, Inyo County |

Sub-adult, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

Sub-adult, coastal San Diego County

© Aaron Wells |

Juvenile with blue tail, Granite Mountains, San Bernardino County

© Jeremiah Easter |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Tail Loss Defense - Caudal Autotomy |

|

|

|

|

| Sub-adult, Kern County with a tail that broke off. |

|

|

|

|

|

Left: Sub-adult with a tail.

Right: After

it lost the tail. |

Tail parts of the skink seen to the left shortly after the tail was released -

Left: the part attached to the lizard;

Right:

the part that was dropped. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Comparison of Gilbert's Skinks with Western Skinks (Plestiodon gilberti and Plestiodon skiltonianus) |

|

|

|

|

Gilbert's Skinks usually have 8 supralabial scales.

Compare with Western Skinks which usually have 7 supralabials. |

Note that the dark stripes on the sides of the tail on juvenile Gilbert's skinks do not extend far onto the tail past the rear leg as they do on the Western Skink.

Compare the two species

More information about the differences between Gilbert's Skinks and Western Skinks. |

Comparison of juvenile skinks:

Top: P. s. skiltonianus - Modoc County

Bottom: P. gilberti rubricaudatus - Kings County

© Patrick Briggs

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Creekside habitat, Kern County |

Habitat,Tehachapi Mountains,

Kern County |

Desert riparian habitat, Inyo County

|

San Diego County coastal sage habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Creekside habitat, 1,450 ft., Kern County |

Creekside habitat, Kern County |

Montane habitat, 5,800 ft.

San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Kern County |

Habitat, Tulare County

© Jonathan Hakim |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

| A sub-adult Western Red-tailed Skink shows the quick serpentine movement of a small skink. Skinks are masters at diving into grass and disappearing. This video opens with the skink wriggled into some grass roots to hide. |

A Western Red-tailed Skink dropped its tail to distract me from trying to catch it. The trick worked - I filmed the tail and its writhing distracting motion, some of which you can see here. |

A little juvenile Western Red-tailed Skink with no tail is discovered underneath a rock. |

This unfortunate Western Red-tailed Skink was found in the wild as it was being swallowed by a California Mountain Kingsnake in Kern County

© Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

2.5 - 4.5 inches long from snout to vent (6.3 - 11.4 cm).

Tail can be up to nearly 2 times the body length.

|

| Appearance |

A large skink with a heavy body, small head, thick neck, small legs, and a smooth, shiny body with cycloid scales.

The tongue is forked, and is frequently protruded.

The long tail is easily detached.

|

| Color and Pattern |

Adult coloring is a uniform olive or light brown with darker edging around the scales, and sometimes the appearance of faded light and dark stripes.

Striping fades with age.

Older adults may develop orange coloring. |

| Male / Female Differences |

Males develop bright reddish-orange coloring on the head during the breeding season.

Females are smaller than males.

Females retain traces of juvenile striping into adulthood.

|

| Young |

Young look very much like adult P. s. skiltonianus, with distinct light and dark stripes (which fade with age) but with a pink tail. (Young in the Panamint and other desert mountains have a blue tail.) However, the dark stripe on the sides of young skinks usually extends only to near the base of the tail.

|

| Identifying Skinks in California - Differences between Western Skinks and Gilbert's Skinks (Plestiodon skiltonianus and Plestiodon gilberti) |

| |

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Rarely found moving about on the ground in the open, however, they are active in the daytime and will occasionally be seen moving in grass, among rocks, or in leaf litter. Often found under surface objects. Gilbert's Skinks are good burrowers, often constructing a shelter by burrowing under rocks and logs.

|

| Defense |

The tail is easily broken off.

When detached, it writhes back and forth to distract a predator while the lizard escapes.

The lizard will grow a new tail.

The bright pink coloring on the tail of a juvenile skink tends to distract a predator from the main body of the lizard.

More information about tail loss and regeneration.

|

| Longevity |

| Lifespan is about 6 years or more. |

| Diet and Feeding |

| Primarily eats a variety of small ground-dwelling invertebrates, but as cannibalism has been reported, small vertebrates are probably occasionally consumed. |

| Reproduction |

Adult Gilbert Skinks become reproductive in their second year of age.

Not much is known about the timing of the breeding season. It varies based on location and elevation and local conditions.

Mating probably occurs in late spring through early summer, most likely from April to June.

Females lay a single clutch of eggs per year in summer, typically from June to August, containing from 3 to 9 eggs.

The eggs are buried in loose moist soil, often under flat stones or in rotting logs.

Females are thought to stay with the eggs to guard them as female Western Skinks do. Maternal care such as this is rare in lizards.

Eggs probably hatch in late Summer, but hatchlings have also been observed as early as May.

|

| Habitat |

Grassland, chaparral, woodlands, and pine forests. Prefers areas where moisture is present nearby.

Has also been found in irrigated ares in desert flats several miles north of the Transverse Ranges.

|

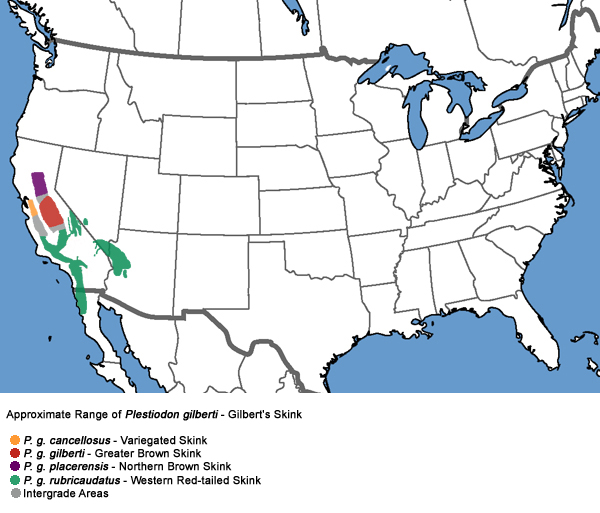

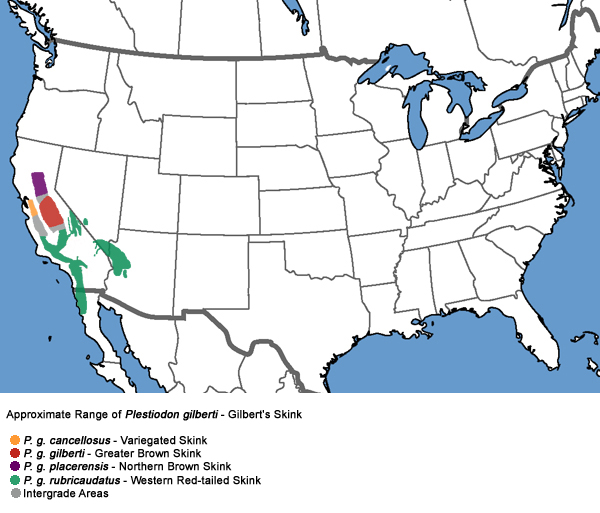

| Geographical Range |

Found from the foothills and middle elevations of the southern Sierra Nevada Mountains and South Coast ranges, south along the Transverse and Peninsular ranges into Baja California.

Isolated populations occur east of the Sierra Nevadas, including Deep Springs and Saline Valleys, and in several desert mountain ranges, including the Kingston, Clark, and Providence Mountains.

The species Plestiodon gilberti ranges from the northern Sierra Nevada foothills from south of the Yuba River through the southern Sierra Nevada, and south through the coast ranges, and the southern interior and mountains, into northern Baja California. Also found in isolated regions east of the Sierras along the Nevada border and into Nevada, and in the southern tip of Nevada into western Arizona.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

From sea level to 7,300 ft. (2.220 m).

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Four subspecies of Plestiodon gilberti are currently recognized:

P. g. cancellosus - Variegated Skink

P. g. gilberti - Greater Brown Skink

P. g. placerensis - Northern Brown Skink

P. g. rubricaudatus - Western Red-tailed Skink

P. g. arizonensis - Arizona Skink - is a fifth subspecies that was formerly recognized in Yavapai County, Arizona.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Brandley et al. (2005 Syst. Biol. 54:373-390) replaced Eumeces with Plestiodon.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles adopted the use of Plestiodon in the sixth edition of their Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America north of Mexico list.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Richmond and Reeder (2002, Evolution 56: 1498-1513) presented evidence that populations previously referred to Eumeces gilberti represent three lineages that separately evolved large body size and the loss of stripes in late ontogenetic stages. Although they considered those three lineages to merit species recognition, they did not propose specific taxonomic changes in that paper. We have placed the name "gilberti" in quotation marks to indicate that it refers to a group composed of several species."

Herpetological Review 2003, 34(3), 196-203.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Richmond and Reeder (2002, Evolution 56: 1498–1513) presented mtDNA evidence that populations previously referred to Plestiodon gilberti represent three lineages that separately evolved large body size and the loss of stripes in late ontogenetic stages. Although they considered those three lineages to merit species recognition, they did not propose speci c taxonomic changes, and subsequently Richmond and Jockusch (2007, Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond. B 274: 1701–1708) and Richmond et al. (2011, Am. Nat. 178: 320–332) have treated them as a single species based on extensive introgressive hybridization between two of the forms and the lack of prezygotic isolation between members of all pairs of them. The results of Richmond and Reeder (2002, op. cit.) contradict the recognition of P. g. arizonensis, which is not differentiated from P. g. rubricaudatus and therefore has been eliminated from this list, and indicate the existence of an unnamed and at least partially separate lineage within P. g. rubricaudatus (their Inyo clade). "

Comments under P. gilberti in the Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles SSAR Herpetological Circular No. 43, 2017.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The 2025 SSAR Names List recoginzes only three subspecies,

merging P. g. cancellosus and P. g. rubricaudatus

and P. g. gilberti and P. g. placerensis.

The new names become:

P. g. gilberti (Van Denburgh, 1896)—Sierran Skink

P. g. rubricaudatus (Taylor, 1936? “1935”)—Western Red-tailed Skink

P. g. ssp. [unnamed]—Inyo Skink

"Richmond and Reeder (2002, Evolution 56: 1498–1513) presented mtDNA evidence that populations previously referred to P. gilberti represent three lineages that separately evolved large body size and the loss of stripes in late ontogenetic stages. Although they considered those three lineages to merit species recognition, they did not propose specific taxonomic changes. Subsequently, Richmond and Jockusch (2007, Proceeding of the Royal Society of London B 274: 1701–1708) and Richmond et al. (2011, American Naturalist 178: 320–332) have treated them as a single species based on extensive introgressive hybridization between two of the forms and the lack of prezygotic isolation between members of all pairs of them. The results of Richmond and Reeder (op. cit.) contradict the recognition of P. g. arizonensis, which is not differentiated from P. g. rubricaudatus and therefore has been eliminated from this list and indicate the existence of an unnamed and at least partially separate lineage within P. g. rubricaudatus (their clade C or Inyo clade). In addition, those results suggest that the former subspecies P. g. gilberti and P. g. placerensis form a single unit (their clade I or Sierran clade), while P. g. cancellosus and P. g. rubricaudatus also form a single unit (their clade A or southwestern clade), findings that are consistent with large areas of intergradation between the pairs of forms (e.g., Jones, 1985, Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. 372.1–3). We, therefore, recognize only three subspecies corresponding to the three lineages inferred by Richmond and Reeder (op. cit.)."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Plestiodon gilberti ssp. [unnamed]—Inyo Skink (Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

Some Arizona populations of this subspecies were formerly known as E. g. arizonensis - Arizona Skink

Eumeces gilberti rubricaudatus - Western Red-tailed Skink (Smith 1946, Stebbins 1966 & 1985 & 2003)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| None |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Scincidae |

Skinks |

Gray, 1825 |

| Genus |

Plestiodon (formerly Eumeces) |

Toothy Skinks |

Duméril and Bibron, 1839 |

| Species |

gilberti |

Gilbert's Skink |

(Van Denburgh, 1896) |

Subspecies

|

rubricaudatus |

Western Red-tailed Skink |

(Taylor, 1936? “1935”) |

|

Original Description |

Eumeces gilberti - Van Denburgh, 1896 - Proc. California Acad. Sci., Ser. 2, Vol. 6, p. 350

Eumeces gilberti rubricaudatus - Taylor, 1936 - Sci. Bull. Univ. Kansas, Vol. 23, p. 446, figs. 72-73, pl. 39

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

Eponyms

First described by Van Denburgh in 1896, the specific name "Plestiodon gilberti" and the species common name "Gilbert's Skink" honor Van Denburgh's Stanford University teacher Charles Henry Gilbert (1859-1928), an American ichthyologist.

See: Biographies of Persons Honored in the Herpetological Nomenclature © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Plestiodon (Toothy Skinks) - Greek - pleistos = most + odontos = teeth

gilberti - honors Gilbert, Charles H.

rubricaudatus - Latin - rubra = red, ruddy + caudatus = bearing a tail (bearing a red tail)

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Lizards |

P. g. cancellosus - Variegated Skink

P. g. gilberti - Greater Brown Skink

P. g. placerensis - Northern Brown Skink

P. s. interparietalis - Coronado Skink

P. s. skiltonianus - Northwestern Skink

P. s. utahensis - Great Basin Skink

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Lemm, Jeffrey. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of the San Diego Region (California Natural History Guides). University of California Press, 2006.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Jones, Lawrence, Rob Lovich, editors. Lizards of the American Southwest: A Photographic Field Guide. Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2009.

Smith, Hobart M. Handbook of Lizards, Lizards of the United States and of Canada. Cornell University Press, 1946.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This animal is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|