|

|

| Adult, Modoc County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Siskiyou County |

Adult, Modoc County |

Adult, Glenn County |

Adult, Santa Clara County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult with orange breeding color on chin, Humboldt County |

Adult showing orange breeding color, February, Santa Clara County |

Underside of a breeding adult, San Bernardino County, showing the orange

breeding coloring. |

|

|

|

|

| Adult with orange breeding color, San Luis Obispo County |

Adult with long intact tail found basking on streamside rocks in Trinity County |

|

|

|

|

Adult with orange breeding color, Sutter Buttes, Sutter County. © Jackson Shedd.

Specimen courtesy of Eric Olson. |

Adult, Contra Costa County |

Adult, Ventura County, © Patrick Briggs |

Adult, Humboldt County. When this skink was discovered hiding under an object, it ran off, jumped into the water and quickly swam to get away.

© Robert Mellinger

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult with orange breeding color on head, Del Norte County © Alan Barron |

Adult found along the American River in Rancho Cordova, Sacramento County.

© Brandon Hunsberger |

Adult found near Anza,

Riverside County © Curtis Croulet |

|

|

|

|

| These adult skinks from the Palos Verdes Peninsula in Los Angeles County have a paler body color than most. This color phase has been described as common in that area by the photographer. © Andrew Louros |

This is a more typically-colored skink from the Palos Verdes Peninsula for comparison with the paler skinks to the left. © Andrew Louros |

Adult, Orange County © Tadd Kraft |

|

|

These two skinks were found under the same board in San Luis Obispo County. The one on the left was found three weeks earlier than the

one on the right, which was found the first week of March, having just developed its bright orange breeding coloring. © Joel A. Germond |

|

|

| Side and top views of an adult seen active on the ground during daylight in Contra Costa County © Yuval Helfman |

|

|

|

|

Subadult, San Luis Obispo County

© Joel A. Germond |

Adult, Santa Clara County

© Yuval Helfman |

This adult Skilton's Skink and Coast Range Fence Lizard were observed basking together frequently in a backyard garden in Marin County in April. This might represent a mate-guarding behavior by a male skink that confused the fence lizard for a female skink, or maybe they're just sharing a good basking spot, unconcerned about any threat from the other lizard. |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Santa Catalina Island,

Los Angeles County © Matthias Lemm |

Adult in breeding condition, Orange County © Cliff Peebles |

An adult Skilton's Skink and a Great Basin Fence Lizard side by side in an Orange County backyard, probably both eyeing the same insect.

© Cliff Peebles |

Adult Coronado Skink, San Diego County © Jack

You can see in this distant shot how much the blue tail on a skink stands out. The light stripes and dark background on the head and body tend to blend into the background making them less noticeable. When a skink with a blue tail is running, it can look like there is a small bright blue snake wriggling instead of a lizard. That will attract the eye of a predator. But unlike the body, the tail is expendable. If a predator grabs it, it will come off easily but it will still move as if it is alive to distract the predator while the rest of the lizard gets away unharmed. |

|

|

|

|

Toothy Skinks, genus Plestiodon, have smooth shiny cycloid scales that are reinforced with bone.

Plestiodon skiltonianus is shown here.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile, Contra Costa County |

Juvenile, Napa County |

Juvenile, Sonoma County © Lou Silva |

Comparison of juvenile skinks:

Top: P. s. skiltonianus - Modoc County

Bottom: P. gilberti - Kings County

© Patrick Briggs

|

|

|

|

|

Recently-hatched juveniles are very small as you can see

with

this one found in Riverside County © Brett Badeaux |

Juvenile, Orange County © Cliff Peebles |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Breeding Season Behavior |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

These adult skinks (presumably a male and a female) were observed in courting behavior at the edge of a trail in Santa Clara County. The male chased the female in and out of a crack in some bark, across the trail, and over various branches and logs.

© Wim de Groot |

|

|

|

|

Two male Skilton's Skinks in the breeding season apparently fighting

over a female hiding nearby in an Orange County yard. © Cliff Peebles |

|

|

| |

|

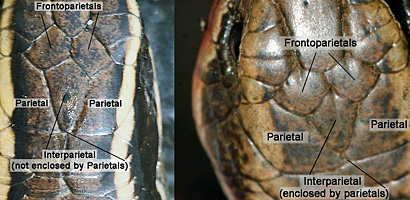

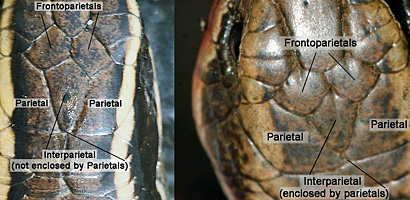

| Identification of Two Subspecies of Plestiodon skiltonianus |

|

|

|

Most Skilton's Skinks -

P. s. skiltionianus, have on the top of their head an interparietal scale that is not enclosed by the parietal scales (Tanner 19571 ).

Click on thumbnail to see a larger image. |

Most Coronado Island Skinks -

P. s. interparietalis, have on the top of their head an interparietal scale that is enclosed by the parietals scales (Tanner 19571 ). |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Comparison of Western Skinks with Gilbert's Skinks (Plestiodon skiltonianus and Plestiodon gilberti) |

|

|

|

|

Note that the dark stripes on the sides of the tail on the Western Skink extend far onto the tail past the rear legs, unlike the stripes on juvenile Gilbert's Skinks.

Compare the two species

More information about the differences between Gilbert's Skinks and Western Skinks. |

Western Skinks usually have 7 supralabial scales.

Compare with Gilbert's Skinks, which usually have 8 supralabials. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

Mixed coniferous forest habitat,

Santa Clara County

|

Rocky habitat along ridge-line in chaparral grassland in Contra Costa County |

Riparian woodland/grassland Habitat, Contra Costa County |

Rocky mixed woodland montane Habitat, Napa County

|

|

|

|

|

Habitat, coastal mixed woodlands-grasslands Monterey County

|

Habitat, forest clearing,

Humboldt County |

Mixed woodland-grassland habitat next to a reservoir, Contra Costa County |

Streamside habitat in coniferous forest, Mendocino County. An adult skink was found wintering under the bark of this downed tree next to a Wandering Salamander. |

|

|

|

|

| Montane habitat, 6,200 ft., San Bernardino County |

Habitat, 1,100 ft. Fresno County. |

Habitat, 2,600 ft., Trinity County |

|

|

|

|

Sandy coastal habitat,

San Luis Obispo County |

Habitat, San Luis Obispo County coast

© Joel A. Germond |

Habitat, Santa Catalina Island

© Matthias Lemm |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

A skink is found under a rock. It bites hard, refusing to let go, then finally runs through dry grass with typical serpentine motion.

|

A juvenile skink loses its blue tail, which writhes around on the ground. This is a defensive measure used to distract the predator which caused the tail to become detached from the rest of the lizard as it tries to escape. |

In this video you can see how the blue tail on a juvenile skink stands out when the lizard moves, especially when it uses its stripes to blend into the vegetation. A predator is more likely to go for the tail, which can detach without hurting the lizard. |

A big adult skink found under a rock in winter in Contra Costa County. |

|

|

|

|

Two male Skilton's Skinks fight over territory during the breeding season on a day in early May in Skamania County, Washington. One bites the other on the head and cannot be shaken off.

© Chris Rombough |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

2.12 - 3.4 inches long from snout to vent (5.4 - 8.6 cm) (Stebbins 2003)

Approximately 7.5 inches in total length.

|

| Appearance |

A small skink with a slim body, small head, thick neck, small legs, and a smooth, shiny body with cycloid scales.

|

| Color and Pattern |

Striped with 3 dark brown and light cream stripes:

A wide dark brown stripe, edged with black, extends from the nose to the tail down the middle of the back,

bordered by two pale stripes which extend from the nose over the eye to the tail.

Two more very dark stripes extend down each side through the eyes, to the tail, where they extend well out onto the tail.

Two more pale stripes extend below these dark side stripes.

The underside is pale or gray.

The tail is gray or dull blue on older adults. Younger adults often retain some of the bright blue coloring.

"In the breeding season reddish or orange color appears on side of head and chin and occasionally on sides, tip, and underside of tail." (Stebbins, 2003) |

| Young |

Tail is bright blue on juveniles.

The stripes on juveniles are more highly contrasted than on adults, whose juvenile colors fade as they age.

|

| Characteristics of Subspecies of Plestiodon skiltonianus (from 1 Tanner 1957) |

P. s. interparietalis - Coronado Skink

"Interparietal enclosed by the parietals in 80 per cent of the population.

Stripes of the body pattern extended onto anterior half or more of tail."

"The extension of the striped pattern on the tail is also seen in specimens of skiltonianus from the coastal ranges of California. However, specimens from north of San Diego County are generally less obviously striped on the tail and if so then with only an occasional one having the interparietal enclosed."

"Diagnosis: this form is most closely related to typical skiltonianus with which it intergrades in San Diego and Riverside counties California. It is different to all other skiltonianus in having the interparietal reduced in size and enclosed posteriorly by the parietals,

the medial and lateral dark stripes extend from the body to or beyond the middle of the tail."

P. s. skiltonianus - Skilton's Skink

"Interparietal rarely enclosed by the parietals. Usually less than 10 per cent even in Los Angeles and San Bernardino Counties; and/or stripes of body pattern not extended on more than the base of the tail."

P. s. utahensis - Great Basin Skink

"Dorsolateral stripe occupying more than half of the second scale row and being nearly one half the diameter of the dark dorsal interspace.

Dark stripe below lateral light stripe rarely present.

Diameter of the dorsolateral stripe usually greater than the length of the first nuchal."

|

| Identifying Skinks in California - Differences between Western Skinks and Gilbert's Skinks (Plestiodon skiltonianus and Plestiodon gilberti) |

| |

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Diurnal, but secretive and not typically seen active.

Occasionally seen foraging in leaf litter.

More commonly found underneath bark and surface objects, especially rocks, where it lives in extensive burrows.

Inactive in cold weather.

|

| Defense |

The tail is easily broken off.

When detached, it writhes back and forth to distract a predator while the lizard escapes.

The lizard will grow a new tail.

The bright blue coloring on the tail of a juvenile skink tends to distract a predator from the main body of the lizard.

Sometimes only the blue tail can be seen as the lizard rushes through grass or leaves.

Occasionally the blue tail is mistaken for a small blue snake.

More information about tail loss and regeneration.

|

| Diet and Feeding |

| Insects, and other small invertebrates, especially spiders and sow bugs. |

| Reproduction |

Females lay 2 - 10 eggs in June and July.

Females guard their eggs until they hatch. Maternal care such as this is rare in lizards.

Eggs hatch in late July and August.

|

| Habitat |

Grassland, woodlands, pine forests, sagebrush, chaparral, especially in open sunny areas such as clearings and the edges of creeks and rivers.

Prefers rocky areas near streams with lots of vegetation. Also found in areas away from water.

|

| Geographical Range |

In California, this subspecies is found throughout the northern part of the state, and in the northern Sierra Nevada and foothills, in the north and south coast mountain ranges, extending south to coastal San Diego County where P. s. interparietalis takes over.

It is also found in the southern Sierra Nevada on the Kern Plateau, the Greenhorn and Piute mountains, Mt. Breckenridge, Caliente Creek, and east of the Sierra Nevada in isolated locations, including the Bodie Hills, the White Mountains, and on the east slope of the Sierra Nevada at Olancha.

Not present in the southern deserts and much of the central valleys.

Also present on Santa Catalina Island. (Jones, Lawrence, Rob Lovich, 2009, shows P. s. interparietalis inhabiting Santa Catalina Island, but the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History has a specimen from the island labelled P. s. skiltonianus, and for that reason I show P. s. skiltonianus inhabiting the island instead of P. s. interparietalis.)

The species Plestiodon skiltonianus ranges beyond California north into inland British Columbia, east into Idaho, Nevada, Utah, and north-central Arizona, and south to the southern tip of Baja California.

1 Tanner 1957 describes some intergrade areas: "Intergrades skiltonianus x interparietalis; San Diego Co.: Escondido; Oceanside; Poway."

|

|

| Elevational Range |

From sea level up to around 8,300 ft. (2,530 meters).

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Several subspecies of Plestiodon skiltonianus are recognized, with three found in California: P. s. interparietalis, P. s. skiltonianus, and P. s. utahensis.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Some taxonomists do not recognize the southern California subspecies P. s. interparietalis. They group it with P. s. skiltonianus.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Brandley et al. (2005 Syst. Biol. 54:373-390) replaced Eumeces with Plestiodon.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles adopted the use of Plestiodon in the sixth edition of their Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America north of Mexico list.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Jonathan Q. Richmond, and Tod W. Reeder, in their 2002 paper * list one specimen from the San Diego State University collection (SDSU 3816) utahensis CA, Inyo Co., Independence Creek at Gray’s Meadow campsite. 36 47.2N, 118 15.2W) that comes from an area fairly far south of the Nevada border on the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains just east of Independence as E. s. utahensis, Great Basin Skink. The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley has specimens of P. skiltionianus (with no subspecies indicated) from Inyo County including Gray's Meadow and another location east of Independence the White Mountains, and the White Mountains.

It is now thought that this subspecies ranges in an isolated region east of Independence and in the White Mountains.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Because the relationships within E. skiltonianus and between E. skiltonianus and the lineages within E. gilberti are complicated (Richmond and Reeder, 2002, Evolution 56: 1498–1513) and need to be analyzed using nuclear markers, we have retained the previously recognized subspecies as legacy taxa."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"We changed the standard English name of this subspecies to make it more informative biologically and have a similar basis to the names of the other two sub- species."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

I have changed the common name to Northwestern Skink in April, 2025,, following the March. 2025 SSAR List, because I don't like possessive eponymous common names.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Plestiodon skiltonianus skiltonianus - Western Skink (The Reptile Database, April, 2025)

Plestiodon skiltonianus skiltonianus - Skilton's Skink (iNaturalist April, 2025)

Plestiodon skiltonianus skiltonianus - Skilton's Skink (Wickipeda April, 2025)

Plestiodon skiltonianus skiltonianus - Skilton's Skink (Hansen and Shedd 2025)

Plestiodon skiltonianus skiltonianus - Skilton's Skink (Stebbins and McGinnis 2018)

Plestiodon skiltonianus - Western Skink (no subspecies) (Stebbins and McGinnis 2012)

Eumeces skiltonianus skiltonianus - Skilton's Skink (Stebbins 2003)

Eumeces skiltonianus skiltonianus - Western Skink (Stebbins 1966)

Eumeces skiltonianus - Common Western Skink (Smith 1946)

Plestiodon skiltonianum - Western Skink (Eumeces quadrilineatus; Eumeces gilberti; Eumeces skiltonianus var. brevipes; Eumeces hallowellii; Eumeces skiltonianus var. amblygrammus; Eumeces skiltonianus. Blue-tailed Lizard; Skilton's Skink; Red-headed Skink; Gilbert's Skink; Blue-tailed Skink) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| None |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Scincidae |

Skinks |

Gray, 1825 |

| Genus |

Plestiodon (formerly Eumeces) |

Toothy Skinks |

Duméril and Bibron, 1839 |

| Species |

skiltonianus |

Western Skink |

Baird and Girard, 1852 |

Subspecies

|

skitonianus |

Northwestern Skink |

Baird and Girard, 1852 |

|

Original Description |

Eumeces skiltonianus - (Baird and Girard, 1852) - Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 6, p. 69

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

First described in 1952 by Baird and Girard, the specific name "skiltonianus" and the subspecies common name "Skilton's Skink" honor Dr. Avery Judd Skilton (1802-1858) an American physician and naturalist who described the Rough-skinned Newt and the Oregon Alligator Lizard.

See: Biographies of Persons Honored in the Herpetological Nomenclature © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Plestiodon (Toothy Skinks) - Greek - pleistos = most + odontos = teeth

skiltonianus - honors Skilton, Avery J. (American naturalist who sent specimens to Baird and Girard.)

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Lizards |

P. g. cancellosus - Variegated Skink

P. g. gilberti - Greater Brown Skink

P. g. placerensis - Northern Brown Skink

P. g. rubricaudatus - Western Red-tailed Skink

P. s. interparietalis - Coronado Skink

P. s. utahensis - Great Basin Skink

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

1 Tanner, Wilmer W. A taxonomic and ecological study of the western skink (Eumeces skiltonianus). Great Basin Naturalist 17:59-94 1957.

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Jones, Lawrence, Rob Lovich, editors. Lizards of the American Southwest: A Photographic Field Guide. Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2009.

Smith, Hobart M. Handbook of Lizards, Lizards of the United States and of Canada. Cornell University Press, 1946.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.Brown et. al. Reptiles of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society,1995.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow,

Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

St. John, Alan D. Reptiles of the Northwest: Alaska to California; Rockies to the Coast. 2nd Edition - Revised & Updated. Lone Pine Publishing, 2021.

Lemm, Jeffrey. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of the San Diego Region (California Natural History Guides). University of California Press, 2006.

* Jonathan Q. Richmond, and Tod W. Reeder. EVIDENCE FOR PARALLEL ECOLOGICAL SPECIATION IN SCINCID LIZARDS OF THE EUMECES SKILTONIANUS SPECIES GROUP (SQUAMATA: SCINCIDAE) Evolution, 56(7), 2002, pp. 1498–1513

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This animal is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|