|

|

|

|

| Adult male, desert side of San Bernardino Mountains, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

| Adult male, desert side of San Bernardino Mountains, San Bernardino County |

Adult male, calling at night in shallow creek in San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

Adult, San Diego County,

© Stuart Young |

Adult, San Diego County,

© Stuart Young |

Adult, San Diego County,

© Jason Jones |

|

|

|

Right after she laid her eggs in a San Diego County stream, this adult female hopped away and burrowed into the sand.

© Emily Mastrelli |

|

|

|

Adult, San Diego County,

© Paul Maier |

Adult, San Diego County,

© Paul Maier |

This enormous adult was observed in San Diego County during a dry year with no creek to breed in. © Andrew Borcher |

|

|

|

Adult, Ventura County

© Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

This Arroyo Toad was found in San Diego County inside the belly of an American Bullfrog along with a Two-striped Gartersnake, which was dead. The toad, however, was alive! When put back in the creek, it hopped away - as you can watch in the video to the right.

© Andrew Borcher

Animals captured and handled under authorization by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. |

This short video shows the amazing recovery of an Arroyo Toad that was swallowed by an American Bullfrog then cut out of its belly still alive. The toad was revived and released into the creek.

© Andrew Borcher

Animals captured and handled under authorization by the Califoirnia Department of Fish and Wildlife. |

| |

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

Juvenile, Santa Ana mountains,

Riverside County |

Juvenile, Ventura County

© Patrick Briggs |

|

|

|

| Recently-metamorphosed juveniles in early July, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

| Recently-metamorphosed juveniles in early July, San Bernardino County |

This recently-metamorphosed juvenile blends in with the sand background on which it spends its early life. |

|

|

|

Recently-metamorphosed juvenile,

San Diego County © Andrew Borcher |

Juvenile, Ventura County

© Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

| |

Juvenile, Ventura County

© Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

|

Juvenile, Ventura County

© Ryan Sikola |

|

Left: juvenile California Toad

Right: juvenile Arroyo Toad

Ventura County © Ryan Sikola |

| |

|

|

| Mating Adults in Amplexus |

|

|

|

A male Arroyo Toad in amplexus with a huge gravid female in mid May in the Palomar Mountains of Riverside County, observed in a shady location in daylight.

© Brett Badeaux. |

This gravid adult female Arroyo Toad is in a stream in San Diego County where she is waiting to find a male so she can lay her eggs and have him fertilize them. © Emily Mastrelli |

|

|

|

Adults in amplexus, Baja California

© James R. Buskirk |

Aduts in amplexus, partially

buried in sand, San Diego County

© Andrew Borcher |

Adult male Arroyo Toad in amplexus with a California Toad in San Diego County (See note below.) © Andrew Borcher |

| |

|

|

| Eggs and Tadpoles |

|

|

|

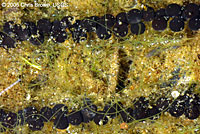

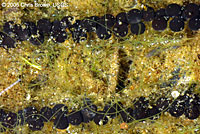

| Close-up of egg strings, San Bernardino County © 2005 Chris Brown, USGS |

Tadpole, Santa Barbara County,

© Ronn Altig |

Tadpoles, San Bernardino County

© 2005 Chris Brown, USGS |

|

|

|

| Young Tadpoles in May, San Bernardino County © Mark Gary |

| |

|

|

| |

Young Tadpoles in May, San Bernardino County © Mark Gary |

|

| |

| Herpetologist Sam Sweet has posted some outstanding descriptions of the biology of Arroyo Toads - their breeding, egg deposition, tadpoles and metamorphs, illustrated with many excellent photographs, and including comparisons with sympatric California Toads. You can see them on www.fieldherpforum.com here and here. |

| |

| Habitat |

|

|

|

| Habitat, desert side of San Bernardino Mountains, San Bernardino County |

Habitat, Mojave River north of Lancaster, Los Angeles County |

|

|

|

| Habitat, San Diego County |

Habitat, Santa Ana Mountains,

Riverside County |

|

|

|

Habitat, San Gabriel Mountains,

Los Angeles County |

Habitat, San Diego County |

Habitat, Ventura County

© Patrick Briggs |

|

|

|

Habitat, Ventura County

© Patrick Briggs |

Habitat with tadpoles in May, San Bernardino County © Mark Gary |

Habitat with recently-metamorphosed juveniles in early July, San Bernardino County © Mark Gary |

|

|

|

Los Angeles County sign,

© William Flaxington |

Arroyo Toad sign, Riverside County |

|

| |

|

|

Short Video

|

|

|

|

Two male Arroyo Toads compete for position in a breeding creek in San Diego County, wrestling with each other, then both calling at the same time. (Baja California Treefrogs can be heard calling in the background.)

© Andrew Borcher |

A male Arroyo Toad calls three times at night from the edge of a creek in San Bernardino County. The video has been edited - the original calls were about a minute apart. |

This short video shows the miraculous recovery of an Arroyo Toad that was swallowed by an American Bullfrog and cut out of its belly. The toad was revived and released into the creek.

© Andrew Borcher

Animals captured and handled under authorization by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. |

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 1.75 - 3.2 inches from snout to vent ( 4.6 - 8.6 cm). (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

|

| Appearance |

A plump and stocky toad with dry, uniformly warty skin.

No cranial crests are present.

Paratoid glands are oval, widely separated, and pale in color toward the front.

Pupils are horizontal. |

| Color and Pattern |

Greenish, gray, olive, dull brown above.

Warts set on dark blotches have brown tips on the tubercles.

No stripe is present down the middle of the back.

There is typically a light stripe or patch across the head and eyelids.

Often there is a patch of light coloring on the sacral humps (in the middle of the lower back.)

Whitish in color below, with no spots or mottling.

The throat is pale on both males and females.

|

| Young |

| Young are pale, often with no dark spots, and warts have tubercles with yellow tips. |

| Larvae (Tadpoles) |

Tadpoles grow to about 1.5 inches long (3.7 cm) before undergoing metamorphosis.

Color is forming a cryptic pattern enabling a tadpole to blend in with the sandy stream substrate.

Tadpoles begin black in color, then begin to show areas of lighter color on top of the tail white patches on their bottoms. Eventually the body coloring becomes a light cryptic shade of tan or olive or gray with black or brown mottling which renders them almost invisible in the sandy substrate.

Look here to see some great pictures of Arroyo Toad tadpoles.

|

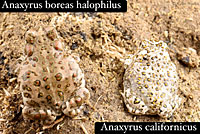

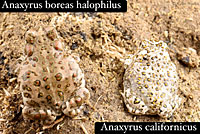

| Comparison with Sympatric Anaxyrus boreas halophilus - California Toad |

(From Sam Sweet, July 2010 online post 1 and post 2)

Adults

Arroyo toads typically have a light stripe or V across the head and eyelids which is lacking on California Toads.

Mature California Toads typically have a pale dorsolateral stripe (a pale light stripe down the middle of the back) which is lacking on Arroyo Toads.

Juveniles

Juvenile Arroyo Toads show the pale V between the eyes, pale spots on the sacral humps, yellow tubercles, and are unmarked ventrally.

Juvenile California Toads have no pale V or pale sacral hump spots, rust-colored tubercles, a pale dorsolateral stripe, and are marked with dark spots ventrally.

Juvenile Arroyo toads are typically found fully exposed in direct sunlight on the sandy banks

of the natal creek.

Juvenile California toads are typically found dug into wet sand at the edge of the creek, or in shade under vegetation.

Tadpoles

Hatchling California Toad tadpoles and Arroyo Toad tadpoles appear very dark.

As they age, Arroyo Toad tadpoles develop white markings on the top of the tail and white patches on their bottom while California Toad tadpoles remain dark.

Mature California Toad tadpoles

appear dark with light mottling.

Mature Arroyo Toad tadpoles appear light with dark mottling.

Arroyo Toad tadpoles tend to remain motionless more than California Toad tadpoles. About a quarter of a small group of California Toad tadpoles will be active at any moment, while only a few individuals in a small group of Arroyo Toad tadpoles will be moving at any moment.

Metamorphosing Arroyo Toad tadpoles show the pale V between the eyes, pale spots on the sacral humps, and yellow tubercles.

Metamorphosing California Toads are darker with no pale V or sacral hump coloring, and rust-colored tubercles.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

| Activity |

Adults are nocturnally active, remaining underground in the daytime, but occasionally seen moving about in daylight or resting at the edge of breeding pools in the breeding season.

Newly-transformed juveniles are diurnal.

Arroyo Toads are active from the first substantial rains from January to March, through August or September. |

| Movement |

| Moves by quickly hopping, instead of walking. |

| Defense |

This toad uses poison secretions from

parotoid glands and warts to deter predators.

Some predators are immune to the poison, and will consume toads. |

| Territoriality |

Toads do not seem to be territorial, but they tend to be fairly sedentary and faithful to breeding sites.

|

| Longevity |

| Life expectancy is generally four years. Females live a bit longer than males. |

| Voice (Listen) |

The advertisement call of the Arroyo Toad is a fast musical trill, about 10 seconds, rising in pitch, and ending abruptly.

This call is similar to that of Anaxyrus punctatus - Red-spotted Toad, but with a lower pitch. It can be heard at a distance. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Adults eat a wide variety of invertebrates, but mostly consume ants, especially nocturnal, trail-forming tree ants.

Juveniles feed mostly on ants and small flies.

Prey is located by vision then the toad lunges with a large sticky tongue to catch the prey and bring it into the mouth to eat.

Unlike all other California tadpoles, Arroyo Toads sift a substrate of fine sediments for food, making them extremely dependent on their unique and fragile habitat of streams with wet sandy stable shorelines. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Fertilization is external, with the male grasping the back of the female and releasing sperm as the female lays her eggs.

Amplexus is axillary - the male grabs the female around her shoulders or armpits.

The reproductive cycle is similar to that of most North American Frogs and Toads. Mature adults come into breeding condition and migrate to streams where the males call to advertise their fitness to competing males and to females. Males and females pair up in amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The adults leave the water and the eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Most males become reproductively mature in their second year, females in their third year.

Mating and egg-laying takes place at the quiet margins of shallow streams from March to July.

Breeding is not triggered by rainfall, but seems to require an increase in air and water temperature to above 11-13 degrees C. (51.8 - 55.4 degrees F.)

Males do not form large calling groups and satellite breeding behavior has not been observed. A single male will take a position at night at a good egg-laying location, typically a flat exposed stream bank with still shallow water, but always with some current flowing through it. There he makes his trilled advertisement call. Females select a male by his sound, then move toward him when they are ready to breed. The male amplexes the female grabbing her behind her forelimbs then she lays her eggs at the male's calling site. She does not typically carry him to another site.

|

Interspecific Amplexus

"Male arroyo toads have been observed in amplexus with small, late-breeding female western toads on three occasions; hybrid larvae hatch, but have massive deformities; most die by Gosner stage 25 (Sweet, 1992).

Dan C. Holland (personal communication) has also observed male arroyo toads in amplexus with large female western toads. Small male western toads are sometimes closely associated with calling male arroyo toads and will repeatedly attempt amplexus with them; male arroyo toads with an attending western toad seldom complete a call without being grasped, and this interference probably reduces mating success (Sweet, 1992)."

AmphibiaWeb. 2020. University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed 14 April 2020. |

| Eggs |

Egg-laying sites are exposed shallow flowing water without any twigs, roots, or debris to tangle the eggs.

Eggs are laid in long strings with two strands of ova, containing an average of 4,700 eggs.

Eggs are subject to mortality from water level changes, from both declines in water level, and flooding: eggs that are stranded when water level drops dry up and do not hatch; eggs that are swept into cooler deeper water are usually attacked by fungus and do not survive. |

| Tadpoles and Young |

Tadpoles hatch from the eggs after about 4 - 6 days, but they cannot swim for several days, during which time a change in the water level can wash them away or strand them.

Eggs and tadpole hatchlings are protected by toxins and are ignored by predators.

Tadpoles begin black in color, then begin to show areas of lighter color on the tails and body, eventually turning to a light cryptic shade which renders them almost invisible in the sandy substrate.

Larvae reach metamorphosis in 72 - 80 days. Most metamorphosis occurs from late May to early July. Sometimes it occurs as early as late April and as late as early October.

Newly metamorposed toads stay 3 - 5 weeks on the exposed sand and gravel bars where they forage in full sunlight in high heat. They take shelter in damp depressions in the gravel. Eventually they become nocturnal, burrowing into dry sand during daylight, and disperse farther from the stream, typically as the stream dries up.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits washes, arroyos, sandy riverbanks, riparian areas with willows, sycamores, oaks, cottonwoods.

Arroyo Toads have extremely specialized habitat needs, which include exposed sandy stream edges with stable terraces for burrowing with scattered vegetation for shelter, and areas of quiet water or pools free of predatory fishes with sandy or gravel bottoms without silt for breeding.

"Arroyo toads are closely associated with low gradient drainages from near sea level to about 1,400 m elevation [4,600 ft.] (to a maximum of 2,440 m [8,005 ft.] in Baja California del Norte), with most remaining populations residing in the 300–1,000 m range [984 - 3280 ft.] (USFWS, 1999a)." (Sweet & Sullivan in Lanoo, 2005).

|

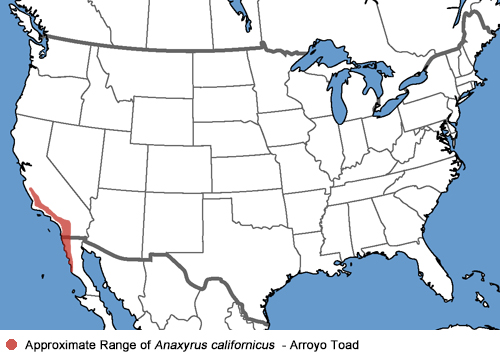

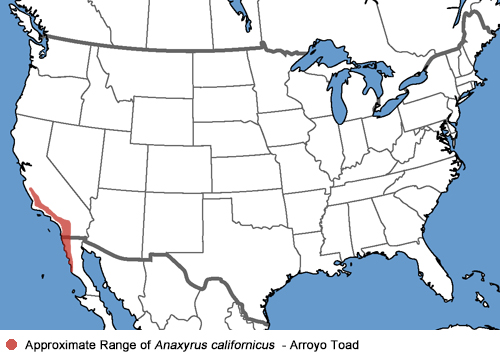

| Geographical Range |

Endemic to California and northern Baja California. Ranges mostly west of the desert in coastal areas, from the upper Salinas River system in Monterey county to northwestern coastal Baja California.

"The arroyo toad has been recorded at six locations on the desert slope (Patton and Myers 1992): the Mojave River, Little Rock Creek, Whitewater River, San Felipe Creek, Vallecito Creek, and Pinto Canyon." CDF&G

1 Ervin et al (2013) presented evidence that "the arroyo toad (Anaxyrus californicus) is not confirmed to occur within the Sonoran Desert portions of Riverside, San Diego, and Imperial counties, California. In the Mojave Desert, the species is currently known from two areas, Littlerock Creek, Los Angeles County and the Mojave River Watershed, San Bernardino County. The validity of the Banner Canyon record reported here remains in question." Records from the Whitewater River, San Felipe Creek, Vallecito Creek, and Pinto Canyon

are probably based on misidentification errors.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Found at elevations in California from near sea level to above 3,900 ft. (1190 m.)

(High elevation record from USGS surveys at Cuyamaca Rancho State Park 2003, 2005.)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

In 1998 Bufo microscaphus was split into two species, Bufo californicus, and B. microscaphus.

Some sources still list Bufo californicus as a subspecies of Bufo microscaphus, Bufo microscaphus californicus.

Formerly included in the genus Bufo. In 2006, Frost et al replaced the long-standing genus Bufo in North America with Anaxyrus, restricting Bufo to the eastern hemisphere. Bufo is still used in many existing references.

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Bufo californicus - Arroyo Toad (Stebbins 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Bufo microscaphus californicus - Arroyo Toad (Stebbins 1954, 1966, 1985)

Bufo californicus - Southern California Toad (Arroyo Toad) (Wright and Wright 1949)

Bufo cognatus californicus - Arroyo Toad (Storer 1925)

Bufo cognatus californicus - Arroyo Toad (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Bufo cognatus (Say 1823)s

|

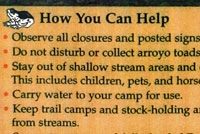

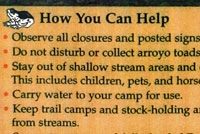

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

This toad is estimated to be absent from 65 to 76 per cent of its historic range. (Thomson, Wright, & Shaffer, 2016)

It is possible that this number is even higher because the historic estimate may be based only on remaining populations, when toads also inhabited streams in areas that were urbanized or altered before the species was known. Remaining population densities of this toad, once historically high, are now relatively low, especially at montane and foothill locations. They are a bit higher at coastal stream locations.

These remaining populations are extremely vulnerable due to isolation from other populations, and to specialized habitat needs which include fragile sandy stream edge habitat and streams that have not been heavily silted. The loss or degradation of this specialized habitat is a major problem. Causes for habitat loss include the results of mining, urban development, grazing cattle, and other sources of stream trampling such as excessive human recreational use, including campgrounds and vehicles driving across streams. Trampling sandy stream banks can crush and destroy all the juveniles, since they feed by remaining on the stream-banks. Exotic aquatic predators such as bullfrogs, fish and crayfish, also reduce toad populations. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Bufonidae |

True Toads |

Gray, 1825 |

| Genus |

Anaxyrus |

North American Toads |

Tschudi, 1845 |

| Species |

californicus |

Arroyo Toad

|

(Camp, 1915) |

|

Original Description |

Bufo californicus Camp, 1915 - Univ. California Publ. Zool., Vol. 12, p. 331

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Anaxyrus - Greek = A king or chief

Californicus - refers to belonging to the state of California - the type locality is Ventura County, California, 1912

Taken in part from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Frogs |

Anaxyrus boreas boreas

Anaxyrus boreas halophilus

Anaxyrus woodhousii

Anaxyrus canorus

Anaxyrus exsul

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

SD Natural History Museum

Pasadena Audubon Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Elliott, Lang, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. Frogs and Toads of North America, a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of California Press Berkeley, California 1925.

Wright, Albert Hazen and Anna Wright. Handbook of Frogs and Toads of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1949.

Davidson, Carlos. Booklet to the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast - Vanishing Voices. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 1995.

1 Edward L. Ervin, Kent R. Beaman, and Robert N. Fisher. Correction of Locality Records for the Endangered Arroyo Toad (Anaxyrus californicus) from the Desert Region of Southern California.

Bull. Southern California Acad. Sci.112(3), 2013, pp. 197–205 © Southern California Academy of Sciences, 2013 DOI

Robert C. Thomson, Amber N. Wright, and H. Bradley Shaffer. California Amphibian and Reptile Species of Special Concern. University of California Press, 2016.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

Special Animals List Note:

At the time of listing, arroyo toad was known as Bufo microscaphus californicus, a subspecies of southwestern toad. In 2001, it was determined to be its own species, Bufo californicus. Since then, many species in the genus Bufo were changed to the genus Anaxyrus, and now arroyo toad is known as Anaxyrus californicus.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G2G3 |

Imperiled - Vulnerable |

| NatureServe State Ranking |

S2 |

Imperiled |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

FE |

Listed as Endangered 1/17/1995 |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

SSC |

Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

EN |

Endangered |

|

|

|