|

|

|

|

| |

Adult, northern Humboldt County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, northern Humboldt County |

Adult, northern Humboldt County |

Adult, covered with dirt,

northern Humboldt County |

|

|

|

| Adult, northern Humboldt County |

Adult, Del Norte County

© Alan Barron |

|

| |

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

Juvenile, northern Humboldt County

|

Juvenile, Del Norte County

© Alan Barron

|

Juvenile, Del Norte County

© Alan Barron

|

| |

|

|

| Boreal Toads From Outside California |

|

|

|

Adult male, Thurston County, Washington, access

courtesy of Jim Lynch, Ft. Lewis Dept. of Fish and Wildlife

|

|

|

|

Adult, Vancouver Island, British Columbia. © Guntram Deichsel

|

Juvenile, Deschutes County, Oregon |

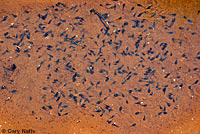

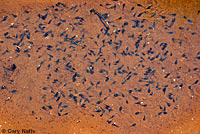

Juvenile toads arranged on rocks in a slow-moving mountain creek in summer, Deschutes County, Oregon |

|

|

|

Metamorph, Owyhee County, Idaho

© Bill Bachman |

Metamorph, Owyhee County, Idaho

© Bill Bachman |

Juvenile, Deschutes County, Oregon |

| |

|

|

| Adults in the Mating Season |

|

|

|

| Males in calling position on lake, Thurston County, Washington, access courtesy of Jim Lynch, Ft. Lewis Dept. of Fish and Wildlife |

|

|

|

| Adults in amplexus, Thurston County, Washington. Access to specimens courtesy of Jim Lynch, Ft. Lewis Dept. of Fish and Wildlife |

Nuptial pad on front foot of adult male, Thurston County, Washington. Specimen courtesy of Jim Lynch, Ft. Lewis Dept. of Fish and Wildlife |

|

| |

|

|

| Eggs and Tadpoles |

|

|

|

Adult female with eggs minutes after deposition, 7,100 ft. Siskiyou County

© Ryan Aberg

|

Eggs are laid in strings similar to those of

California Toads. |

Mass of young tadpoles,

Deschutes County, Oregon |

|

|

|

Tadpoles, Deschutes County, Oregon

Eyes are inset from the edge of the head. |

Tadpole, Deschutes County, Oregon

|

|

|

|

| Tadpole, Deschutes County, Oregon |

Mature Southern Long-toed Salamander larva eating a Boreal Toad tadpole,

5,800 ft. Shasta County © Ryan Aberg |

|

| |

|

|

| Comparisons With Larvae and Tadpoles of Sympatric Species |

| |

|

|

| |

Comparison of Treefrog Tadpole (Pseudacris regilla group) (Top)

with Toad Tadpole

(Anaxyrus boreas) (Bottom)

(Click on picture for a better view) |

|

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

| Habitat, temporary pools on coastal plain, Humboldt County |

Habitat, Humboldt County coast

|

Breeding habitat with tadpoles, Deschutes County, Oregon |

More pictures of this toad and its habitat in the Northwest are available on our Northwest Herps page.

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

| A toad gives a release call after he is picked up and gently grasped across the back. (It may sound like this toad is suffering, but it is not being harmed. This is a warning call, the same one he makes when another male toad comes into his territory or climbs onto his back and grabs him tightly with his legs.) |

An adult Boreal Toad hops around a coastal plain in Humboldt County.

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults grow to 2 - 5 inches from snout to vent ( 5.1 - 12.7 cm). (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A large and robust toad with dry, warty skin.

No cranial crests are present.

Parotoid Glands are oval and well-developed.

Pupils are horizontal.

|

| Color and Pattern |

The ground color is Greenish, tan, reddish brown, dusky gray, or yellow.

Rusty-colored warts are set on dark blotches.

There is much dark blotching above and below, becoming all dark at times.

The throat is pale on both males and females.

A light stripe is usually present on the middle of the back. |

| Male/Female Differences |

Males are usually less blotched than females and have smoother skin.

Females are larger than males and more stout.

During the breeding season, males have

dark nuptial pads on the thumbs and the inner two digits of the hands. |

| Young |

Young have no dorsal stripe immediately after transformation.

The bottoms of their feet is bright orange or yellow.

|

| Larvae (Tadpoles) |

Tadpoles are dark brown with eyes inset from the edges of the head.

The tip of the tail is rounded.

They grow to about 2.25 inches (5.6 cm) in length before undergoing metamorphosis.

|

| Comparison with A. b. halophilus - California Toad |

A. b. boreas:

"Considerable dark blotching both above and below. Sometimes almost all dark above..."

A. b. halophilus

"Generally less dark blotching than in Boreal Toad. Head wider, eyes larger (less distance between upper eyelids), and feet smaller."

(Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Life History and Behavior |

| Activity |

Diurnal and nocturnal. Often diurnal after winter emergence, becoming nocturnal in the summer after breeding.

|

| Movement |

| Slow moving, often with a walking or crawling motion along with short hops. |

| Defense |

| This toad uses poison secretions from

parotoid glands and warts to deter predators. Some predators are immune to the poison, and will consume toads. Still other predators such as ravens have learned to avoid the poisons by eating only their viscera through the stomach. |

Territoriality

|

| Male Western Toads are not territorial except when breeding. Amplexing males will kick away other males, and males may briefly fight other males at breeding sites. |

| Longevity |

| Western Toads have been reported living at least 9 years. |

| Voice (Listen) |

Most male Boreal Toads do not have a pronounced vocal sac in which sound can resonate, so the volume of its calls is very low, which makes them not useful for attracting female toads at any great distance from the calling site. The calls are faint when compared to the loud calls of the sympatric Pacific Treefrog which gernally share the breeding pond. But male toads do make a call during breeding aggregations. The call has been described as a high-pitched plinking

sound, like the peeping of a chick, repeated several times. The sound of a group of males calling has been compared to the sound of a distant

flock of geese.

Most male Boreal Toads do not have a pronounced vocal sac. The lack of a large pouch in which sound can resonate accounts for the low volume of the calls. The calls are so low they are not useful for attracting female toads at any great distance from the calling site. The call is not very loud when compared to the call of the sympatric Pacific Treefrog. But male toads do make a call during breeding aggregations. The call has been described as a high-pitched plinking

sound, like the peeping of a chick, repeated several times. The sound of a group of males calling has been compared to the sound of a distant

flock of geese. Some Boreal Toads have been found to make advertisement calls with a pronounced vocal sac. (See Zachary Long's findings below.)

Calls are produced at night and during the day during the short breeding season. Males make their call primarily when they are in close

contact with other males. Rather than being advertisement calls made to attract females, these calls are generally considered encounter or aggressive calls, or release calls, which serve to maintain territory and spacing between males. The calls may also serve other purposes - a lone

male toad has been observed calling.1 It could also be possible that female toads are attracted to the sounds of male encounter calls, and can judge a male's condition by his call, similar to the function of an advertisement call.

Unreceptive females may also produce a release call when grasped on the back by a male. Males and females sometimes make a release call when grabbed across the back by a human hand. (See video above.)

On his website, and in his note in Herp Review (Zachary Long, Herpetological Review 41(3), 2010.), Zachary Long presents video and audio evidence of Boreal Toads making advertisement vocalizations in a wetland south of Whitecourt, Alberta, Canada. In his videos, you can clearly see that the toad has a vocal sack. When compared with the calls I have recorded in Washington State, you can easily hear the difference between them. You can listen to his recordings and watch his videos here.

|

| Diet and Feeding |

Diet consists of a wide variety of invertebrates, including worms, spiders, moths, beetles, and ants.

The prey is located by vision, then the toad lunges and quickly extends its large sticky tongue to catch the prey and bring it into the mouth to eat.

Tadpoles consume algae and detritus, including the scavenged carrion of fish and other tadpoles. |

| Reproduction |

Breeding is aquatic.

Fertilization is external, with the male grasping the back of the female and releasing sperm as the female lays her eggs.

Amplexus is axillary - the male grabs the female around her shoulders or armpits.

The reproductive cycle is similar to that of most North American Frogs and Toads. Mature adults (4 - 6 years old) come into breeding condition and migrate to ponds or ditches. Males and females pair up in axillary amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The adults leave the water and the eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Breeding can occur any time from January to early July, depending on the elevation, winter snow levels, or rainfall amounts, taking place shortly after toads emerge from their hibernation sites and migrate to the breeding wetlands. Scent cues are used to find the way to the breeding site.

In some areas, breeding occurs after snowmelt when breeding ponds refill with water. Amplexus and egg-laying takes place in still or barely moving waters of seasonal pools, ponds, streams, and small lakes. |

| Eggs |

Eggs are laid in long strings with double rows, averaging 5,200 eggs in a clutch.

Fresh eggs contain some of the toad's toxin to protect them from predation, but this poison decreases over time.

Eggs hatch in 3 to 10 days, often longer in the colder waters of higher elevations. |

| Tadpoles and Young |

Tadpoles are dark brown and grow to about 2.25 inches (5.6 cm) in length before undergoing metamorphosis.

Large schools of tadpoles often feed together in shallow water.

Tadpoles enter metamorphosis in 30 - 45 days, usually in summer or early fall, depending on water temperature - colder water delays metamorphosis. In years of extreme winter weather, especially at higher elevations, metamorphosis might be only a few weeks before snow begins to accumulate again.

When in the process of metamorphosis, many tadpoles are often seen in aggregations at the edge of a pond in various stages of metamorphosis. After most tadpoles undergo metamorphosis, large numbers of newly-transformed toads are often seen hopping around the edges of the water. They may stay and spend the winter at the border of their natal wetland, or they may disperse to nearby sites away from the pond.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits a variety of habitats, including marshes, springs, creeks, small lakes, meadows, woodlands, forests, and desert riparian areas.

In the spring and early summer, toads are often found at the edge of water, sometimes basking on rocks and logs. At other times of the year they are also found farther from the water where they spend much of their time in moist terrestrial habitats.

Toads use rodent holes, rock chambers, and root system hollow as refuges from heat and cold.

|

| Geographical Range |

The species Anaxyrus boreas is found in most of California, northern Baja Caifornia, Nevada, Idaho, western Montana, northern and central Utah, western and south central Wyoming, central Colorado, and extreme north central New Mexico, most of Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, western Alberta, and extreme southeastern Alaska. Toads found in the Rocky Mountains have undergone a severe decline.

The subspecies Anaxyrus boreas boreas is found across the northern tip of California, east through Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming, and north through western Oregon and Washington, through British Columbia, all the way to southern Alaska.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Anaxyrus boreas is found from sea level to over 11,800 ft. (3,600 m.) (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Formerly included in the genus Bufo, and Bufo is still used in many existing references.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 2006, Frost et al replaced the long-standing genus Bufo in North America with Anaxyrus, restricting Bufo to the eastern hemisphere.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Two subspecies of Anaxyrus boreas are traditionally recognized in California - Anaxyrus boreas halophilus, and Anaxyrus boreas boreas.

(Anaxyrus nelsoni has also been treated as a subspecies of Anaxyrus boreas: A. b. nelsoni, but this is controversial.)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List does not recognize subspecies of Anaxyrus boreas:

"The English name of Boreal Toad is sometimes used broadly for this taxon, especially for populations sometimes referred to A. b. boreas (Baird and Girard, 1852), and refer Western Toad to A. b. halophilus. Two subspecies (A. b. boreas, A. b. halophilus) have been inconsistently recognized historically and we do not recognize them here given the substantial need for additional taxonomic work on this complex. The A. boreas group generally is considered to include a number of isolated populations that appear to be diagnosable as species. Some have been recognized as species and/or subspecies and others have no history of taxonomic recognition. From this complex, A. canorus, A. exsul, and A. nelsoni are now generally accepted, and three additional allopatric populations have been named as species (A. monfontanus, A. nevadensis, and A. williamsi) recently have been described. Nevertheless, issues raised in older works by Cook (1983, Publications in Natural Sciences. National Museum of Canada: 89), Goebel (2005, in Lannoo, M. [editor], Amphibian Declines, University California Press: 210–211), Pauly (2008, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Texas at Austin), and Goebel et al. (2009, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 50: 209–225), using genetics, morphology, and advertisement calls, suggest that additional diversity remains unrecognized. The published genetic data used to investigate this group has been restricted to mitochondrial sequences, which have proven to be problematic in general (Dufresnes and Jablonski, 2022, Science 377: 127), and this complex is no exception. In such approaches, for example, the mitochondrial network and phylogenetic analyses of by Gordon et al. (2017, Zootaxa 4290: 123–139) found A. boreas to be paraphyletic with respect to A. canorus, A. exsul, and A. nelsoni. Their work also suggests that the subspecies A. b. boreas and A. b. halophilus may be valid species, but Goebel et al. (op. cit.) found A. b. halophilus to be polyphyletic within the broader A. boreas group. A comprehensive review of the A. boreas group that includes nuclear DNA and dense geographic sampling is needed and likely will reveal a complex evolutionary history, and corresponding taxonomy, for this group that spans a considerably large and complex geographic region."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------The SSAR 2017 names list does not recognize subpsecies of Anaxyrus boreas:

"Two nominal subspecies are generally recognized, although Goebel (2005, in Lannoo, M. J. [ed.], Amphibian Declines: the Conservation Status of United States Species. Univ. of California Press: 210–211) discussed geographic variation and phylogenetics of the A. boreas (as the Bufo boreas) group (i.e., A. boreas, A. canorus, A. exsul, and A. nelsoni), and noted other unnamed populations of nominal A. boreas that may be species.

Populations in Alberta, Canada, assigned to A. boreas have a distinct breeding call and vocal sacs (Cook, 1983, Publ. Nat. Sci. Natl. Mus. Canada 3; Pauly 2008, PhD Dissertation, Univ. Texas at Austin); the taxonomic implications of this warrant investigation. Goebel et al. (2009, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 50: 209–225) suggested on the basis of molecular evidence that nominal Anaxyrus boreas is a complex of species (as suggested previously by Bogert, 1960, The influence of sound on the behavior of amphibians and reptiles. Washington DC: American Institute of Biological Sciences 179) that do not conform to the traditional limits of taxonomic species and subspecies (and which we do not recognize here for this reason) and that some populations assigned to this taxon may actually be more closely related to Anaxyrus canorus and A. nelsoni—a problem that calls for additional elucidation. Reviewed by Muths and Nanjappa (2005, in Lannoo, M. J. [ed.], Amphibian Declines: the Conservation Status of United States Species. Univ. of California Press: 392–396) and Dodd (2013, Frogs of the United States and Canada, John Hopkins Univ. Press: 47–65). "

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The SSAR 2012 names list no longer recognized this or any subspecies of A. boreas:

"Goebel et al. (2009, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 50: 209-225) suggested on the basis of molecular evidence that nominal Anaxyrus boreas is a complex of species (as suggested previously by Bogert, 1960, Animal Sounds Commun.: 179) that do not conform to the traditional limits of taxonomic species and subspecies (and which we do not recognize here for this reason) and that some populations assigned to this taxon may actually be more closely related to Anaxyrus canorus and A. nelsoni - a problem that calls for additional elucidation."

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In 2017, a new species was discovered within A. boreas in Nevada and named A. williamsi.

(Michelle R. Gordon, Eric T. Simandle & C. Richard Tracy. A diamond in the rough desert shrublands of the Great Basin in the Western United States: A new cryptic toad species (Amphibia: Bufonidae: Bufo (Anaxyrus)) discovered in Northern Nevada. Zootaxa 4290 (1): 123-139 © 2017 Magnolia Press.)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Anaxyrus boreas [no subspecies] (Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

Bufo boreas boreas - Boreal Toad (Stebbins 1954, 1966, 1985, 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Bufo boreas halophilus - Northwestern Toad

(Baird's Toad, Mountain Toad, Columbian Toad, Small-spaded Toad, Northern Toad, Western Toad) (Wright and Wright 1933-1949)

Bufo boreas halophilus - Northwestern Toad (Storer 1925)

Bufo boreas halophilus - Northwestern Toad - Baird's Toad, Small-spaded Toad (Bufo columbiensis, part; Bufo halophilus, part; Bufo microscaphus) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Bufo columbiensis (Cope 1889)

Bufo halophila (Baird and Girard 1853)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| Anaxyrus boreas is becoming uncommon in many areas of the Pacific Northwest, the Rocky Mountains and other areas, probably due to environmental changes caused by habitat loss, especially loss of wetlands, and chemical contamination of wetlands. Toads are also slow-moving and are frequently run over by traffic as they cross roads at night during their breeding migrations, which could also contribute to their loss. |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Bufonidae |

True Toads |

Gray, 1825 |

| Genus |

Anaxyrus |

North American Toads |

Tschudi, 1845 |

| Species |

boreas |

Western Toad |

(Baird and Girard, 1852) |

| Subspecies |

boreas |

Boreal Toad

|

(Baird and Girard, 1852) |

|

Original Description |

Bufo boreas Baird and Girard, 1852 - Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 6, p. 174

Bufo boreas boreas Baird and Girard, 1852 Boreal Toad

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Anaxyrus - Greek = A king or chief

Boreas - Greek = north wind or northern - which refers to the northern range

Taken in part from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Frogs |

Anaxyrus boreas halophilus

Anaxyrus californicus

Anaxyrus woodhousii

Anaxyrus canorus

Anaxyrus exsul

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

1 Davidson, Carlos. Booklet to the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast - Vanishing Voices. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 1995

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Corkran, Charlotte & Chris Thoms. Amphibians of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, 1996.

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

Leonard et. al. Amphibians of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, 1993.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Elliott, Lang, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. Frogs and Toads of North America, a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of California Press Berkeley, California 1925.

Wright, Albert Hazen and Anna Wright. Handbook of Frogs and Toads of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1949.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This toad is not on the Special Animals List. There are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|