Northwestern Pond Turtle - Actinemys marmorata

(Baird and Girard, 1852)= Northern Western Pond Turtle / Western Pond Turtle / Pacific Pond Turtle

= Emys marmorata marmorata / Actinemys marmorata marmorata / Clemmys marmorata marmorata

Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

Red: range of this species in California

Actinemys marmorata - Northwestern Pond Turtle

Orange: range of similar species

Actinemys pallida - Southwestern Pond Turtle

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

Volunteer to monitor Marin County Pond Turtles.

Training session, March 1st, 2025 with Marin Water:

https://www.marinwater.org/VolunteerPrograms

| Adults | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult female, Butte County © Jackson Shedd |

Adult female, Solano County © Adam Clause. Animal captured and handled under state Scientific Collecting Permit and released at point of capture. |

Adult male, Kings County © Patrick Briggs |

Adult male in a Madera County mountain creek © Brian Hubbs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, El Dorado County © John Bailey |

Adult male pond turtle on right, Red-eared slider on left, El Dorado County © John Bailey |

Note the white throat characteristic of an adult male © John Bailey |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult female, Mendocino County | Adult, Fresno County © James R. Buskirk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Napa County (showing inguinals on right) © James R. Buskirk | Adult, Mendocino county | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Del Norte County near Crescent City. © Alan Barron | Adult, Colusa County © Kinji Hayashi |

Adult, Napa County © James R. Buskirk |

Adults, Modoc County © James R. Buskirk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult female, Fresno County © Patrick Briggs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, El Dorado County © Brandon Huntsberger |

Adult on left with juvenile on the right, Sacramento County. © Brandon Huntsberger |

Adult, Kings County © Patrick Briggs | Adult, Sacramento County © Noah Morales |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This small male was photographed as it was being helped across the busy road it was trying to cross in August in Trinity County © Grayson B. Sandy |

Kings County © Brian Hubbs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult Northwestern Pond Turtle with two non-native Red-eared Sliders on each side of it, El Dorado County © John Bailey | Adult male, Glenn County © Grayson B. Sandy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, El Dorado County © John Bailey "We watched the muskrat swim to the board where the turtle was sunning. He climbed on without disturbing the turtle, slowly advanced asserting his dominance. The turtle tucked in his head then backing up he dropped off the edge." RB |

Basking adults, Shasta County © James R. Buskirk |

Adult male on left, adult female on right Lake County, © Brian Hubbs |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, southern Del Norte County © Bradford R. Norman |

Adult female, Modoc County © Max Roberts |

Adult male, Modoc County © Max Roberts |

Basking adults, Solano County © Zachary Cava |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pond turtles in Marin County © Brian Hubbs |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Piebald Males From the San Joaquin Valley | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

"Large old males from San Joaquin Valley, Calif. may be marked with large areas of beige and pinkish beige." (Stebbins, 2003) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult male, Fresno County © Patrick Briggs | Adult male, Kings County, (showing piebald melanism which is characteristic of males in the San Juaquin Valley.) © Patrick Briggs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Piebald adult males, Fresno County © Brian Hubbs |

Adult male from near Oakley on the eastern edge of Contra Costa County (This is where the range of A. marmorata meets A. pallida but since it's near the delta and the Central Valley, I'm going to assume it's A. marmorata.) © Grayson Sandy |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Differences Between Males and Females (genus Actinemys) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Females usually have a pale throat mottled with dark markings. |

Adult female with mottled throat © Grayson Sandy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Males usually have a pale throat with no dark markings. |

Males have raised areas towards the rear of the head, as you can see on this male from Santa Clara County. © Brian Hubbs |

Males have a slightly concave plastron Left: Male Right: Female © Pierre Fidenci |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juveniles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hatchling, Mendocino county | Hatchling, Fresno County © Patrick Briggs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

These 2 turtles are neonate A. pallida. Both were found in early May, in different years in Alameda County. |

A "tiny juvenile" A. marmorata found in mid-June, San Mateo County. |

Hathling A. pallida, 7 May 2005, Alameda County. The shell shows the granular character of the natal scutes, or areolae, typical among hard-shelled turtles of all families, but only present on tiny juveniles during the spring months. © James R. Buskirk |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Siskiyou County © Kinji Hayashi |

Juvenile from Northern California © Brian Hubbs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pond Turtle Tracking |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| These are Santa Clara County turtles with transmitters attached to their shells. An antenna with a radio receiver that can find these transmitters is used to find the turtles and track their movement in order to study their behavior. Transmitters on females like the one on the far left are placed on the side of the shell to prevent obstacles to males during breeding. The transmitters are removed without damaging the shells when research is completed. © Neil Keung |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This Santa Clara County turtle travelled away from a dry creek in Summer to bury itself in an upland location above the creek in oak woodland habitat. It will stay there until the following Spring when it returns to the creek. The turtle was found by tracking a transmitter which you can see was attached to its shell. © Neil Keung |

Find the turtles. Both of these adult pond turtles were tracked with radio receivers to where they were hiding in shallow creeks in Santa Clara County. Both are very well camouflaged and could easily be overlooked. © Neil Keung |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Comparison With Red-eared Sliders - Trachemys scripta elegans | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The head, neck, and throat of the female Western Pond Turtle is mottled, with no red stripe behind the eye. | The head of the male Western Pond Turtle is dark with no red stripe behind the eye, and the throat is white. © Grayson B. Sandy |

There is usually a prominent red stripe behind the eye of the Red-eared Slider. | Some older or melanistic adult Red-eared Sliders do not have a red stripe behind the eye. © Will Kohn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

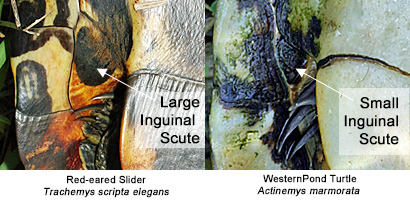

| A useful way to differentiate Western Pond Turtles from Red-eared Sliders, according to wildlife biologist Brandon Stidum, "...is to look at the marginal scutes 8-12 (...the scutes above the tail, or back scutes). Sliders have bifid or slightly forked scutes, where Western Pond Turtles do not; theirs are all smooth and do not split (except for traumatic injuries, but it’s usually only one or a few, not all scutes). The forking in the tail gives red-eared sliders the appearance that the tail is serrated or split in appearance. While looking for the presence and size of inguinal and axillary scutes is the best way to differentiate between the 2 once you have them in hand, a good way to do it from a distance is to look at the back scutes of the turtles." | Two adult Red-eared Sliders (left) compared with a much smaller adult Pacific Pond Turtle (right). © Jeff Ahrens. Animal capture and handling authorized under SCP or specific authorization from CDFW. |

Ventral view of four adult Red-eared Sliders, with a much smaller adult Pacific Pond Turtle in the middle. © Jeff Ahrens. Animal capture and handling authorized under SCP or specific authorization from CDFW. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Potential Identification Confusion with Melanistic Red-eared Sliders | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melanistic adult Red-eared slider - Trachemys scripta elegans Riverside County. © Bob Parkard |

Melanistic adult Red-eared slider, (without red on the head) Riverside County © Bob Parkard |

Melanistic adult Red-eared with no red marks behind the eyes © Will Kohn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult Pond Turtle, Mendocino county | Adult female Pond Turtle © Grayson Sandy |

Adult male Pond Turtle | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Click to enlarge |

Introduced melanistic sliders and old sliders whose red "ears" have faded, are often difficult to distinguish from the California native Western Pond Turtle, especially at a distance in the field, and even in hand. According to Bob Packard, with the Western Riverside County MSHCP Biological Monitoring Program, his organization confirms the identification of these turtles based on the presence of large inguinal and axillary scutes on the sliders, which are absent on the pond turtles (see illustration to the left) and by an interesting behavioral clue: the majority of sliders tend to be aggressive, biting readily, while pond turtles are far more reluctant to bite. You can also use the information described above about differentiating the two species from a distance by observing the rear marginal scutes, or back scutes. More pictures of melanistic sliders can be seen above. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western Pond Turtle Eggs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Western Pond Turtle Eggs, © Patrick Briggs |

Western Pond Turtle Life Cycle: Adult, Juvenile, and Egg, Butte County. © The Chico Turtle Lab |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, river, Mendocino County | Habitat, large pond, Marin County | Habitat, forest creek, Mendocino County | Habitat with turtle, San Joaquin County © James R. Buskirk |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, large lake, Sacramento County | Habitat, meadow in Siskiyou County © Kinji Hayashi |

Habitat, Napa County © James R. Buskirk |

Habitat, Tulare County © Patrick Briggs |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| River habitat, Sacramento County © Noah Morales |

Habitat, Del Norte County near Crescent City. © Alan Barron |

Habitat, southern Del Norte County © Bradford R. Norman |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos of the Similar Southwestern Pond Turtle Species | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Southwestern Pond Turtles compete for limited basking space on a small pond. | Southwestern Pond Turtles basking in the sun. |

Southwestern Pond Turtles in an Alameda County pond. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. The Special Animals List recognizes western pond turtles as one full species - Emys marmorata - Western Pond Turtle. It does not track the species by the two formerly recognized subspecies nor does it recognize the 2014 two species of pond turtles theory (as this site does.) Special Animals List Notes 7/23: western pond turtle 1) CNDDB tracks western pond turtle at the full species level, based on the determination that the previous subspecies split was not warranted (Spinks, P.Q. and Shaffer, H.B. 2005. Range-wide molecular analysis of the western pond turtle (Emys marmorata): cryptic variation, isolation by distance, and their conservation implications. Molecular Ecology 14(7):2047- 2064). 2) Genus was updated to Emys based on findings in: Spinks, P.Q. and Shaffer, H.B. 2009. Conflicting mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies for the widely disjunct Emys (Testudines: Emydidae) species complex, and what they tell us about biogeography and hybridization. Systematic Biology. 58(1):1-20. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | G3G4 | Vulnerable - Apparently Secure |

| NatureServe State Ranking | S3 |

Vulnerable |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | PT | Proposed for ESA listing as Threatened |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | None | |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | SSC | Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management | S | Sensitive |

| USDA Forest Service | S | Sensitive |

| IUCN | VU | Vulnerable |

|

|

||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -