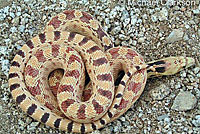

Gophersnake - Pituophis catenifer

Great Basin Gophersnake - Pituophis catenifer deserticola

Stejneger, 1893(= Great Basin Gopher Snake)

Description • Taxonomy • Species Description • Scientific Name • Alt. Names • Similar Herps • References • Conservation Status

Pituophis catenifer deserticola - Great Basin Gophersnake

Range of other subspecies in California:

Purple: Pituophis catenifer affinis - Sonoran Gophersnake

Orange: Pituophis catenifer annectens - San Diego Gophersnake

Red: Pituophis catenifer catenifer - Pacific Gophersnake

Light Green: Pituophis catenifer pumilus -

Santa Cruz Island Gophersnake

Gray: General area of intergradation

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

Listen to a Gophersnake

hissing defensively

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Inyo County © Sean Fekete | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Inyo County | Inyo County adult with its head flattened defensively into a triangular shape. | Adult, San Bernardino County © Michael Clarkson |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Inyo County | Adult, Inyo County | Adult, Inyo County © Grigory Heaton | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Bernardino County © John Worden |

Adult, Victorville, San Bernardino County © 2004 Roxanne Ward | Adult, Kern County © Patrick Briggs |

Adult, Kern County © Brad Alexander |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Mono County © Noah Morales The snake is in a high defensive pose in the picture on the right, ready to strike. |

Adult, Kern County © Todd Battey | Underside of adult, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Inyo County © Patrick Briggs | Adult, Inyo County © Patrick Briggs | Adult, Inyo County © Patrick Briggs | Adult, Inyo County © Patrick Briggs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Inyo County © Patrick Briggs | Underside of adult, Kittitas County, Washington |

Adult, Kern County © Patrick Briggs | Adult, Kern County © Patrick Briggs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Inyo County | Adult, San Bernardino County © Guntram Deichsel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, San Bernardino County © Terry Goyan |

Adult, Inyo County. Gophersnakes are often seen basking while stretched out on a sunny road with lots of kinks in the body that break up the shape of the body to make it look less like a potential meal to any predatory bird flying above. Sometimes they will stop moving and assume this position when they have been spotted as they are crossing a road. |

This Great Basin Gophersnake is a resident of a Kern County desert property. It has been observed living under the garage, engaged in mating activity with two other snakes, and climbing the deck over a front door to get on the roof. © Garth Weals |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Interesting or Unusual Great Basin Gophersnakes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This patternless striped adult snake was found dead in Morongo Valley in San Bernardino County. © Adya Black | Hypomelanistic adult, Kern County © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juveniles | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile in defensive stance, Inyo County | Apparently axanthic juvenile with no brown, tan, or yellow coloring. Found in Lassen County east of Susanville. © Don Cain |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Snakes From Intergrade Areas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult from Kern County intergrade area where P. c. catenifer intergrades with P. c. deserticola © Patrick Briggs |

Adult from Kern County intergrade area where P. c. catenifer intergrades with P. c. deserticola © Patrick Briggs |

Adult from Kern County intergrade area where P. c. catenifer intergrades with P. c. deserticola © Patrick Briggs |

Adult from Lassen County intergrade area where P. c. catenifer intergrades with P. c. deserticola. © Debra Frost |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult from Los Angeles County intergrade area where P. c. annectens intergrades with P. c. deserticola. © Patrick Briggs | Adult from Lassen County intergrade area where P. c. catenifer intergrades with P. c. deserticola. © Debra Frost |

Adult from Lassen County intergrade area where P. c. catenifer intergrades with P. c. deserticola. © Debra Frost |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, from Tule Lake, Siskiyou county, where P. c. deserticola intergrades with P. c. catenifer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, from Tule Lake, Siskiyou county, where P. c. deserticola intergrades with P. c. catenifer. | This pink-sided adult is from the area in Los Angeles County where San Diego and Great Basin Gophersnakes interbreed. © Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, from Tule Lake, Siskiyou county, where P. c. catenifer intergrades with P. c. deserticola. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult, Modoc County © Max Roberts | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breeding | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A pair of mating adults from Lassen County © Debbie Frost | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gophersnakes Feeding | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Debbie Frost relocated the breeding pair shown above, and one of them crawled down a hole, quickly coming back up with a kangaroo rat. The snake then crawled into the shade made by Debbie's shadow and ate while she watched. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Juvenile Pacific Gophersnake, Mariposa County, eating a Western Fence Lizard © Daniel Harris |

This dead juvenile Pacific Gophersnake was found in Sutter County. It appears to have a leg, but on closer inspection, it is the leg of what is probably an alligator lizard that broke through the snake's side after the snake swallowed it. © Kevin Bryant |

Adult Pacific Gophersnake, Kings County, preparing to eat its namesake mammal - a gopher. © Patrick Briggs | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adult Pacific Gophersnake in a bird's nest eating a duck egg, Kings County, © Patrick Briggs |

A juvenile Pacific Gophersnake eating a Coast Range Fence Lizard in Sonoma County © Gérard Menut | Matt Maxon and Johanna Turner were hiking in Big Tujunga Canyon in Los Angeles County when they discovered a large dead rodent that appeared to have been partially swallowed and spit out. (Left) On returning to the same spot about two hours later, they noticed the rodent was gone, and soon discovered a San Diego Gophersnake swallowing it. (Right) Did the snake kill the rodent, attempt to eat it, then spit it out and return later to try again, or was more than one predator involved? We'll never know, but that sure is more than a mouthful. © Matt Maxon and Johanna Turner. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gophersnake Predation | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A California Kingsnake killing a Pacific Gophersnake for dinner in Contra Costa County. © Tim Dayton |

Gophersnakes are sometimes preyed upon by birds of prey, or raptors. Here, a San Diego Gophersnake is carried off by a Red-tailed Hawk in San Luis Obispo County. © Joel A. Germond | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| California Kingsnakes are powerful predators capable of eating other snakes almost as large as they are. Here you can see one eating a Pacific Gophersnake. © Patrick Brigg |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Danger of Plastic Netting to Snakes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Suzanne Camejo found this San Diego Gophersnake in an apricot tree which it had climbed probably trying to raid a Mockingbird nest. The snake was entangled in synthetic netting used to protect the fruit from birds. Suzanne and her friends cut the netting, which had dug into the snake's skin, to free the snake. They were repaid with the hissing and striking of a very stressed-out snake, but one that was now free to crawl away and continue to rid the garden of rodents and rabbits. Although netting is used as a natural method to deter agricultural pests, as well as for erosion control, it can be a great hazard to some animals, especially snakes. Photos © Suzanne Camejo |

This San Diego Gophersnake was found entangled in synthetic "wildlife netting" used as a barrier to rodents and other pests. After freeing two snakes that were found entangled in the netting, the property owner removed the netting to protect the snakes. © Osa Barbani |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This San Diego Gophersnake found in Orange County, was rescued after it was trapped in a tarp with small mesh that was used to cover backyard stuff. Snakes will try to crawl through any open mesh, not just that used in plastic netting. © Stacy Schenkel |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How to Tell the Difference Between Gophersnakes and Rattlesnakes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Harmless and beneficial gophersnakes are sometimes mistaken for dangerous rattlesnakes. Gophersnakes are often killed unnecessarily because of this confusion. (It's also not necessary to kill every rattlesnake.) It is easy to avoid this mistake by learning to tell the difference between the two families of snakes. The informational signs shown above can help to educate you about these differences. (Click to enlarge). If you can't see enough detail on a snake to be sure it is not a rattlesnake or if you have any doubt that it is harmless, leave it alone. You should never handle a snake unless you are absolutely sure that it is not dangerous. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Follow these links to see more pictures of this subspecies from the Northwest and from the Southwest. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, 6,000 ft. Inyo County mountains | Habitat, San Bernardino County desert | Habitat, Siskiyou County | Habitat, San Bernardino County desert | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, 6,000 ft. Inyo County mountains |

Habitat, Lassen County desert | Habitat, San Bernardino County desert | Habitat, Inyo County desert | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Habitat, Owens Valley, Inyo County | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Short Videos | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A Great Basin Gophersnake crawls across a road and into the grass in the Owens Valley. | A large gophersnake crawls off a road in a Mojave desert canyon. | A distressed Pacific Gophersnake shakes its tail rapidly, which makes a buzzing sound as the tail touches the ground. This behavior might be a mimic of a rattlesnake's rattlng, or it could be a similar behavior that helps to warn off an animal that could be a threat to the gopher snake. | A Great Basin Gophersnake crawls across a dirt road in Okanagan County, Washington. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Here's a little taste of roadcruising (edited down from a much longer drive) - driving, driving, driving, then finally a snake is spotted on the road. This one is an intergrade gopher snake from the sagebrush desert of eastern Siskiyou County. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists: https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals. A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page. If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings. Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website. This snake is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California. |

||

| Organization | Status Listing | Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking | ||

| NatureServe State Ranking | ||

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) | None | |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) | None | |

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife | None | |

| Bureau of Land Management | None | |

| USDA Forest Service | None | |

| IUCN | ||

|

|

||

Return to the Top

© 2000 -