|

|

| Adult, coastal San Diego County © Linda Morgan |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Inyo County desert |

Adult, Riverside County desert |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, coastal Riverside County |

Adult, coastal Riverside County |

Adult, coastal San Diego County

© Linda Morgan |

|

|

|

Adult, eastern San Emigdio Mountains, L.A. County © Patrick Briggs

(This snake shows reddish coloring on the front half and tan coloring on the back half of its body.)

|

Adult, Imperial County desert

© Paul Maier |

|

|

|

|

Adult, San Bernardino County

Photos by Patrick H. Briggs, courtesy Tom Moisi |

Adult, Kern County desert

© Brad Alexander |

Adult, coastal San Diego County

© Paul Maier |

|

|

|

|

Underside of adult, Tehachapi mountains, Kern County

© Todd Battey |

Adult, San Diego County near the Orange County border

© Stacy Schenkel |

Adult with a lot of black on the front,

San Diego County.

© TexturePop.com |

Adult, about 5,000 ft. elevation in Mono County © Megan McManama |

|

|

|

|

This adult coachwhip was photographed for about 20 minutes as it poked its head in and out then slowly emerged from a hole barely larger than itself in

San Diego County © Douglas S. Brown |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, northern San Diego County near the Orange County border © Stacy Schenkel |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Riverside County

© Brody Trent

Somewhat forward-facing eyes and good eyesight help coachwhips find prey. |

An adult periscoping, probably to search for prey, in Riverside County

© Steven Elliott |

This Imperial County adult has a very light-colored tail. © Ryan Craig |

Adult, coastal Los Angeles County

© Gregory Litiatco |

|

|

|

|

The species Coachwhip gets its name from the appearance of the scales

on the tail which were thought to look like a braided leather whip. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Adult Red Racers From Outside of California |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Yuma County, Arizona |

Tracks on a sandy road.

A large racer crossed part of this road in Arizona. When I startled the snake, it quickly doubled back the way it came.

|

|

|

|

|

Adult, Nye County, Nevada

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

| This juvenile snake, about 15 inches in length, wandered into a house in Orange County. © Kiahna Garcia |

Juvenile, San Diego County |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Breeding Behavior |

|

|

|

|

Two Red Coachwhips mating in late May in Orange County. © Mark Pugs

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Red Coachwhips Feeding and Drinking and Predation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jay Snow took this series (left to right, top to bottom) of a Red Coachwhip trying to eat a live Southern Desert Horned Lizard over a period of 44 minutes. The snake failed to swallow the lizard and crawled away. In the last picture you can see that the lizard lay prone for several minutes after the coachwhip left then took up to 15 minutes to clean the saliva off its face before slowly walking away, no doubt thankful for the row of horns behind its head.

© Jay Snow

|

|

|

|

| Adult Red Coachwhip eating a juvenile Northern Mohave Rattlesnake, San Bernardino County © Yvette Watson |

A Red Coachwhip eats a juvenile Southern Pacific Rattlesnake in Riverside County © Steven Elliott |

|

|

|

|

Coachwhips are excellent climbers. This large adult is eating a

dove high in a tree in Maricopa County, Arizona. © Darrell Roberts |

Adult Red Coachwhip eating a San Diego Alligator Lizard, Ventura County.

© Samantha Zahringer.

Samantha Zahringer watched this coachwhip eat the lizard by her back door. Her kids saw the snake raise its neck, sway for a moment, then strike quickly. Two other lizards nearby froze while the snake swallowed. When the snake finished, the lizards finally moved away.

|

|

|

This adult coachwhip was observed drinking at a water feature in the Kern County desert. It was not interested in the large grasshoppers found nearby, only in the water.

© Garth Weals |

|

|

|

|

| Though they are not mainly snake-eaters, Coachwhips will eat whatever they can find and overpower, including snakes. Darrel Roberts found this one eating a young Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake in his Phoenix driveway one morning. © Darrel Roberts |

This Red Coachwhip became prey to a red-shouldered hawk in San Diego County.

© Dennis Rudloff |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Plastic Landscaping Netting Can Be Hazardous to Snakes |

|

|

|

|

This Red Coachwhip was found dead, entangled in mesh laid on the ground as part of an abandoned landscaping project on a highway in Palmdale, Los Angeles County.

© Paul J. Burke

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, coastal Riverside County |

Habitat, San Diego County

desert riparian |

Habitat, early spring, San Gorgonio

Pass desert, Riverside County |

Habitat, Inyo County desert |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, San Bernardino

County desert |

Habitat, Riverside County desert |

Habitat, San Diego County desert |

Habitat, desert flats, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, Los Angeles County desert

|

Habitat, desert on the CA Border,

Nye County, Nevada

|

Habitat, San Diego County

desert mountains |

Habitat, San Diego County

desert mountains |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, coastal San Diego County |

Coastal habitat, San Diego County |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

I saw this Red Coachwhip foraging in the desert in San Diego County before it saw me. After turning in my direction, it saw me, raised its head off the ground in a state of alert, wiggled its neck back and forth while holding its head still, then turned around and raced away over the rocks into a bush.

|

A juvenile Red Coachwhip ready to shed its skin is found under a board in Riverside County then races away into the grass. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

Not Dangerous - This snake does not have venom that can cause death or serious illness or injury in most humans.

Commonly described as "harmless" or "not poisonous" to indicate that its bite is not dangerous, but "not venomous" is more accurate. (A poisonous snake can hurt you if you eat it. A venomous snake can hurt you if it bites you.)

|

| Length |

Adults are 36 - 66 inches long (91 - 167 cm.) (Stebbins & McGinnis, 2012)

The only longer snake in California is the Gophersnake.

Hatchlings are about 13 inches long.

|

| Appearance |

A slender fast-moving snake with smooth scales, a large head, somewhat forward-facing eyes with round pupils, a thin neck, and a long thin tail.

(There is no well-defined stripe lengthwise on the body in this species.)

Large scales above the eyes.

17 rows of scales at midbody.

The braided appearance of scales on the tail (like a whip) gives this species its common name. |

| Color and Pattern |

Color is variable; light brown, pink or reddish above.

The dark coloring is interspersed with light coloring creating a banded or saddled appearance, with dark coloring surrounding the light scales.

Dark (often black) blotches across the top of the neck, sometimes with white, sometimes with body color, in-between.

(Sometimes the neck and much of the head are solid black.)

Color typically changes to a solid tan or reddish coloring along the length of the long thin tail.

Black and yellow phases of this subspecies are found outside of California.

|

| Young |

Young have blotches or cross-bands with dark brown or black on a light brown or tan background.

Black markings on the neck may be faint or not present.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Active in the daytime. Able to tolerate high temperatures.

Moves very quickly.

Coachwhips are good climbers, able to climb bushes and trees to hunt for bird nests and pursue arboreal lizards.

Often seen moving quickly even on hot sunny days, but often seen basking on roads in early morning or resting underneath boards or other surface objects.

Frequently run over by vehicles and found dead on the road, partly due to the tendency of this snake to stop and eat small road-killed animals.

|

| Defense |

| Often strikes aggressively when threatened or handled. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats small mammals including bats, nestling and adult birds, bird eggs, lizards, snakes, amphibians, and carrion.

Hatchlings and juveniles will eat large invertebrates.

The ability to tolerate high temperatures enables

this snake to hunt heat-dependent lizards when they are active. High speed allows it to run down the fast-moving

lizards.

Hunts crawling with head the held high above the ground, occasionally moving it from side to side to aid in binocular vision and depth perception.

The prey is overcome and crushed with the jaws or crushed beneath loops of the body then eaten without constriction.

An adult Red Racer was observed swallowing the head and neck of a live Southern Pacific Rattlesnake that it had pinned to the ground with its body.

(Herpetological Review 45(2) 2014)

|

| Lifespan |

The lifespan of a Coachwhip is approximately 13 years in the wild, and 20 years in captivity.

(Stewart, H. 2018. Animal Diversity Web.) |

| Reproduction |

Presumably mates in May.

Females are oviparous laying a clutch of 4 - 20 eggs in early Summer (June - July). (Stebbins, 2003)

Eggs hatch in 45 - 70 days.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits open areas of desert, grassland, scrub, and sagebrush, including rocky, sandy, flat, and hilly ground.

Avoids dense vegetation where it cannot move quickly, but will climb trees.

Takes refuge in rodent burrows, under shaded vegetation, and under surface objects.

|

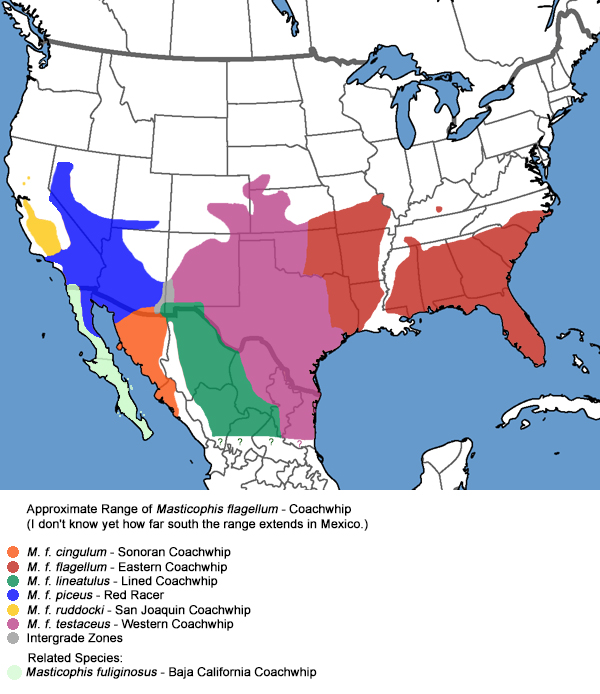

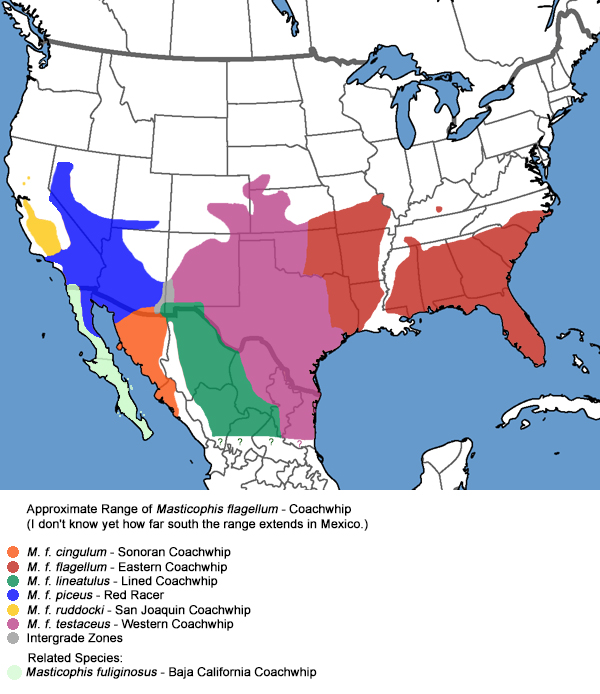

| Geographical Range |

Coachwhip

The species Masticophis flagellum - Coachwhip, occurs very widely across the southern half of the U.S. from southern California east to Florida, and far south into Mexico, including northeast Baja California.

Red Coachwhip

The subspecies covered on this page, Masticophis flagellum piceus - Red Coachwhip (Red Racer), is found throughout southern California from Ventura county to the Baja California border and north around the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada Mountains though the Great Basin desert into northwestern Nevada, and south through Nevada and much of Arizona to part of Sonora and Baja California. It apparently intergrades with C. f. ruddocki in eastern Kem County. It is missing from much of the urbanized coastal portion of Los Angeles County due to land development.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

The species is found from below sea level in the desert to around 8,250 ft. (2,515 m). (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

In a study published in 2017, Myers et al found that the genus Masticophis is monophyletic with respect to Coluber. Following this taxonomy Coluber constrictor mormon will remain but the species previously placed in the genus Masticophis on this website have been returned to that genus:

Coluber flagellum - is now Masticophis flagellum

Coluber fuloginosus - is now Masticophis fuliginosus

Coluber lateralis - is now Masticophis lateralis

Coluber taeniatus - is now Masticophis taeniatus

(Edward A. Myers, Jamie L. Burgoon, Julie M. Ray, Juan E. Martinez-Gomez, Noemi Matias-Ferrer, Daniel G. Mulcahy, and Frank T. Burbrink.

Coalescent Species Tree Inference of Coluber and Masticophis. Copeia 105, No. 4, 2017, 642–650)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(Some researchers recognize Masticophis fuliginosus - Baja Coachwhip, which also occurs in California, as a subspecies of M. flagellum - M f. fuliginosus.)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Former Taxonomy Used Here

North American snakes formerly placed in the genus Masticophis were changed to the genus Coluber based on a 2004 paper * by Nagy et al. Utiger et al. (2005, Russian Journal of Herpetology 12:39-60) supported Nagy et al. and synonymized Masticophis with Coluber. This has not been universally accepted. The most recent SSAR list has hinted that the genus Masticophis might be re-instated: "Burbrink (pers. comm.) has data to reject Nagy et al.’s hypothesis but we await publication of these data before reconsidering the status of Masticophis."

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Myers et al. (2017, Copeia 2017: 642–650), using combined mtDNA and nDNA data, demonstrated that C. constrictor and Masticophis spp. were sister taxa. Therefore, we recognize Masticophis as a genus. The standard English name was changed to reflect this. Myers et al (2024, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlae018) did not find strong support for some of these subspecies but further research is required to clarify species delineations."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Mastiophis piceus piceus - Red Racer (Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

Masticophis flagellum piceus - Red Racer (Hansen and Shedd 2025)

Coluber flagellum piceus (Nagy et al 2004)

Coluber flagellum piceus - Red Racer (Stebbins & McGinnis 2018)

Masticophis flagellum piceus - Red Racer (Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Masticophis flagellum piceus - Red Racer (Stebbins 2003)

Masticophis flagellum piceus - Red Coachwhip (Red Racer) (Stebbins 1985)

Masticophis flagellum piceus - Red Racer (Wright & Wright 1957, Stebbins 1966)

Masticophis flagellum piceus - ssp. of Common Whipsnake (Stebbins 1954)

Coluber flagellum frenatus - Red Racer (Bascanion flagellum frenatum; Zamensis flagellum flagellum; Zamenis flagellum; Zameis flagelliformis frenatus; Bascanion flagellum frenatum; Bascanium flagelliforme; Bascanium flagelliforme testaceum, part; Bascanium testaceum; Bascanium flagelliforme piceum; Herpetodryas flavigularis; Drymobius testaceus. Western Whip Snake; Yellow Coach-whip Snake, part; Arizona Coach-whip Snake; Coppery Whip Snake) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

Masticophis flagellum piceus - Western Whip Snake (Van Denburgh 1897)

Masticophis flagellum piceus (Cope 1892)

Masticophis flagellum (Shaw 1802)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| None |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Colubridae |

Colubrids |

Oppel, 1811 |

| Genus |

Masticophis |

Coachwhips and Whipsnakes |

Baird & Girard, 1853 |

| Species |

flagellum |

Coachwhip |

Shaw, 1802 |

Subspecies

|

piceus |

Red Racer (or Red Coachwhip) |

(Cope, 1892) |

| Original Description |

Masticophis flagellum - (Shaw, 1802) - Gen. Zool., Vol. 3, p. 475

Masticophis flagellum piceus - (Cope, 1892) - Proc. U.S. Natl. Mus., Vol. 14, p. 625

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

| Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Masticophis - Greek - mastix = whip + ophis = referring to the body shape and braided appearance of the tail

flagellum - Latin = whip - refers to the body shape and braided look of tail

piceus - Latin = pitch black - refers to the black coloring often present on the head and neck

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

| Alternate Names |

Red Racer

Coluber flagellum piceus

|

| Related or Similar California Snakes |

M. f. ruddocki - San Joaquin Coachwhip

M. fuliginosus - Baja California Coachwhip

S. h. hexalepis - Desert Patch-nosed Snake

S. h. mojavensis - Mohave Patch-nosed Snake

S. h. virgultea - Coast Patch-nosed Snake

|

| More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Snakes of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bartlett, R. D. & Alan Tennant. Snakes of North America - Western Region. Gulf Publishing Co., 2000.

Brown, Philip R. A Field Guide to Snakes of California. Gulf Publishing Co., 1997.

Ernst, Carl H., Evelyn M. Ernst, & Robert M. Corker. Snakes of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution Press, 2003.

Taylor, Emily. California Snakes and How to Find Them. Heyday, Berkeley, California. 2024.

Wright, Albert Hazen & Anna Allen Wright. Handbook of Snakes of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1957.

* Z. T. Nagy, Robin Lawson, U. Joger and M. Wink. Molecular systematics of Racers, Whipsnakes and relatives (Reptilia: Colubridae) using Mitochondrial and Nuclear Markers. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research (Volume 42 pages 223–233). 2004

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This snake is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|