Red dots: some of the areas where populations of non-native Red dots: some of the areas where populations of non-native

Ambystoma mavortium have been found in California.

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

List of Non-Native Reptiles and Amphibians

Established in California

|

This species has been introduced into California. It is not a native species.

|

It is unlawful to import, transport, or possess this species in California

except under permit issued by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

(California Code of Regulations, Title 14, Excerpts, Section 671)

|

| Ambystoma mavortium - Western Tiger Salamander - found in California, subspecies not known. |

|

|

|

| Blotched adult, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County © Alan Barron |

Blotched adult, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County © Alan Barron |

Blotched adult, 11.5 inches long, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County © Alan Barron |

|

|

|

| Greenish adult, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County © Alan Barron |

Spotted adult, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County © Alan Barron |

Blotched adult, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County © Alan Barron |

|

|

|

| Adult with remnant gills, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County © Alan Barron |

Adult, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County

© Alan Barron |

Variously patterned adults, Grass Lake, Siskiyou County © Alan Barron |

|

|

|

| Adult, Kern County © William Flaxington |

Adult male, Mono County © Adam Clause |

| |

|

|

| |

Adult, Mono County © Noah Morales |

|

| |

|

|

| Ambystoma mavortium x Ambystoma Californiense Hybrids |

|

|

|

Monterey County adult hybrid of A. t. mavortium - Barred Tiger Salamander and

A. californiense. © Gary Nafis.

Specimen courtesy of Brad Shaffer & Dylan Dietrich-Reed, UC Davis.

|

|

Herpetologist Sam Sweet has made a fascinating public forum post regarding introduced tiger salamanders hybridizing with California Tiger Salamanders in Santa Barbara County which you can see along with the ensuing discussion here.

|

| Ambystoma mavortium melanostictum - Blotched Tiger Salamander |

| |

|

| Adults |

|

|

|

| Adult, Idaho © John Huffman |

|

| |

|

| Aquatic Larvae |

|

|

| Large larva in water, 7,000 ft. Wyoming |

|

|

Large larva, removed from water temporarily to show color.

|

Large larva in water, 7,000 ft. Wyoming |

| |

|

|

Ambystoma mavortium mavortium - Barred Tiger Salamander

|

|

|

|

| Adult, found during a November rain in San Diego County © Sean Kelly |

Adult, Cochise County, Arizona |

|

|

|

| Adult, Lake County. Courtesy of Brad Shaffer & Dylan Dietrich-Reed, UC Davis |

Adult, Cochise County, Arizona |

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Cochise County, Arizona |

|

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Cochise County, Arizona |

|

| |

|

|

| |

More Pictures |

|

| |

|

|

| Ambystoma mavortium nebulosum - Arizona Tiger Salamander |

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Coconino County, Arizona |

|

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Coconino County, Arizona |

|

|

|

|

Aquatic larvae,

Coconino County Arizona |

Aquatic larvae,

Coconino County, Arizona

|

More Pictures |

| |

|

|

| Habitat in California |

|

|

|

Habitat, Grass Lake, 5,000 ft.

Siskiyou County |

CalTrans sign, Grass Lake

Siskiyou County

|

Habitat, Grass Lake, 5,000 ft.

Siskiyou County

|

| |

|

|

| |

Habitat, Black Lake, Mono County

© Noah Morales |

|

| |

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

A Barred Tiger Salamander crosses a wet road on an August night in the grasslands of Southeast Arizona.

|

An Arizona Tiger Salamander crosses a road in the mountains of Arizona on a

rainy summer night, moving away from a breeding pond and back into the woods. |

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Ambystoma mavortium is the second largest terrestrial salamander in North America, after Dicamptodon (the Giant Salamanders.)

Adults measure from 3 - 6.5 inches long (7.6 - 16.5 cm) from snout to vent.

|

| Appearance |

A large thick-bodied lunged salamander with small protuberant eyes, and a wide, round snout.

Tubercles are present on the underside of the feet.

Four morphs of A. mavortium are known:

Typical metamorphosed adults,

Cannibalistic metamorphosed adults,

Typical gilled adults,

Cannibalistic gilled adults |

| Color and Pattern |

Bacground is yellowish - greenish with large dark bars across the upper body.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

A member of the Mole Salamander family (Ambystomatidae) whose members are medium to large in size with heavy, stocky bodies.

Ambystomatid salamanders have two distinct life phases:

- Larvae hatch from eggs laid in water where they swim using an enlarged tail fin and breathe with filamentous external gills. - Aquatic larvae transform into four-legged salamanders that live on the ground and breathe air with lungs.

In some cases adults do not transform from the aquatic larval stage to a terrestrial form, instead they stay in the water throughout their lives where they grow legs, reach adult size and breed, but retain their gills and finned tails.

This retention of juvenile features in an adult is called either paedomorphosis (also spelled pedomorphosis) or neoteny.

Adults are paedomorphic or paedomorphs, or neotenic adults and they are facultative paedomorphs - meaning that some individuals metamorphose while others do not. (There are some Ambystomatid species elsewhere where individuals never undergo metamorphosis. These are called obligate paedomorphs.

|

| Activity |

Adults spend much of their lives underground, often utilizing the tunnels of burrowing mammals such as moles and ground squirrels.

Adults spend most of their time burrowing underground, emerging occasionally on rainy nights and during migration to breeding ponds, which occurs on rainy nights.

Large neotenic adults are sometimes found.

Some adults in permanent wetlands without fish are neotenic (paedomorphic). Terrestrial adults burrow into the soil using their forelimbs, or use mammal burrows. During freezing conditions, terrestrial adults burrow below the frost line, while neotenic adults overwinter underwater.Males tend to be slightly smaller than females.

|

| Longevity |

| Captive neotenic adults live as long as 25 years while captive terrestrial adults have lived as long as 16 years. |

| Defense |

| Terrestrial adults assume a defensive pose when threatened, raising up on their hind legs, arching the tail and waving it, and releasing sticky noxious secretions from skin glands along the top of the tail. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Terrestrial adults feed on anything they can catch and overcome, mainly a variety of invertebrates, including insects and insect larvae and worms, along with some small vertebrates including lizards and mice and even small snakes.

Larvae feed on a wide range of invertebrates including insects and insect larvae, mollusks, leeches, crayfish, tadpoles, small fishes, and salamander larvae. Prey size increases as larvae grow larger. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Fertilization is external with a male passing a spermatophore to a female.

Breeding occurs in seasonal wetlands and permanent wetlands without fish, including lakes, slow streams, cattle tanks, quarry ponds, and flooded ditches.

Adults migrate from overwintering sites to wetlands used for breeding.

Migration is usually triggered by warm spring rains a few weeks after ice melts in northern climates.

In California, this would typically be in November or in the late winter and spring, but it appears that in some areas they breed year-round. The Grass Lake population's breeding migration apparently occurs during heavy Fall rains when they fall before the first freeze.

Males migrate before females, sometimes several weeks before, and stay longer at the breeding site where they usually outnumber the females.

Adults remain in the water for a short period - possibly up to a month.

California A. mavortium have been observed metamorphosing typically after they are 8 or 9 inches in length, with some adults remaining neotenic, sometimes exceeding 12 inches in length, as long as their pond doesn't dry out. (Sweet, 2010) |

| Eggs |

Females lay an average of 38 - 59 eggs.

Depending on the subspecies, eggs are laid either singly, in clusters, or in strings, and are attached to submerged twigs and branches.

Eggs hatch in 8 - 9 days. |

| Young |

Temperature, food supply, predation, and the persistence of water in the breeding wetlands all determine the length of the larval period, which is 10 weeks or more.

Larvae may overwinter, transforming the following year, or even later.

On rainy nights, newly-metamorphosed salamanders move overland from the breeding wetlands to upland sites which can be near the wetlands or some distance away.

|

| Habitat |

Throughout their natural range, Western Tiger Salamanders inhabit ponds, lakes, reservoirs, ditches, cattle ponds, temporary pools, and streams in a variety of types of vegetation - deserts, sagebrush, grassland, meadows, and forests.

|

| Geographical Range |

Natural Distribution

Ambystoma mavortium is the most widespread species of salamander in North America, ranging along the Atlantic coast from Long Island south to Florida, and west as far as eastern Washington and Oregon, north into Canada, and south into Mexico. Within this range, some populations are introduced and some historical populations have been extirpated.

Tiger Salamanders introducted into California are variable in appearance. To illustrate some of the variety in the apparance of this species, several different subspecies from California and other western states are shown here.

The subspecies A. m. mavortium occurs naturally in parts of Texas, eastern New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, and eastern Wyoming, and Colorado, and has been introduced into a large area of Southern Arizona.

The subspecies A. m. melanostictum occurs natually in Washington, Idaho, Montana, Colorado, the Dakotas, and barely into Oregon, Nebraska, Colorado and Utah, and north into British Columbia.

The subspecies A. m. nebulosum occurs natually in much of Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado, extending into small areas of Idaho, Wyoming, Nevada, and south into Mexico.

Distribution in California

There may be one native population in the state, but most likely the species has been introduced into several isolated locations in California as a result of "bait-bucket" release.

At one time

The Grass Lake population of A. m. melanostictum was thought to be natural, but they were apparently established from larvae used as fishbait that were obtained from the Great Plains region.

There is one population in California at MacDoel near the Oregon border, which, along with two other nearby populations in southern Oregon, are genetically similar to natural populations found in Washington and Oregon. These salamanders might represent either a natural or human-assisted expansion of salamanders from native populations in Washington and Oregon, or they might be native populations remnant from a large meta-population of A. mavortium that was isolated when the deserts formed after the glaciers receded during the Pleistocene era, approximately 14,000 years ago. (Johnson et al., 2010)

There has been so much interbreeding between different forms of alien tiger salamanders in California that it is not possible to know their exact origin and subspecies. Using genetic analysis of A. mavortium from many locations in the West, Johnson et al, 2010, determined that they have originated from multiple sources in the Great Plains region, "...introduced as a by-product of the sport fishing bait industry."

|

|

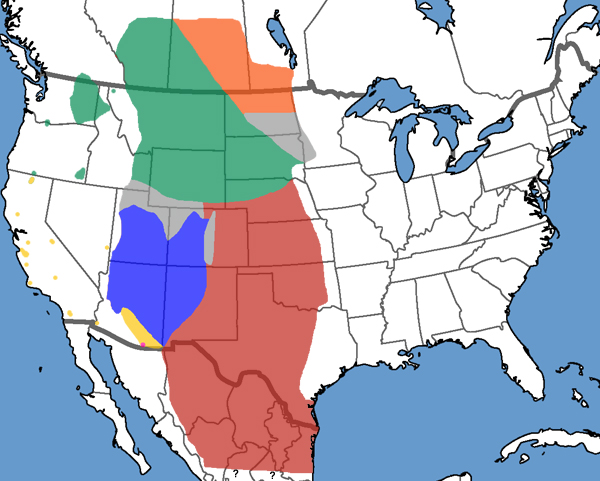

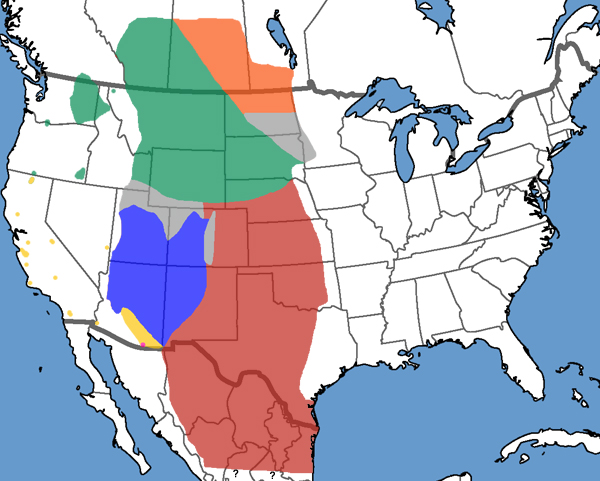

Approximate Range of Ambystoma mavortium - Western Tiger Salamander

Orange = A. m. diaboli - Gray Tiger Salamander

Red = A. m. mavortium - Barred Tiger Salamander

Green = A. m. melanostictum - Blotched Tiger Salamander

Blue = A. m. nebulosum - Arizona Tiger Salamander

Fuchsia = A. m. stebbinsi - Sonoran Tiger Salamander

Gray = Intergrade Range

Yellow = Range of introduced or unknown subspecies

(Complete range and subspecies information in Mexico not known.)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Since alien A. mavortium larvae originated from more than one location and have hybridized with A. californiense in some locations, A. mavortium found in California are most likely genetically mixed and do not correspond to any particular subspecies.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Some researchers have abandoned the recognition of subspecies of Ambystoma mavortium due to information on genetic variations in the species which may not support the traditionally-recognized subspecies. Others have split Ambystoma. tigrinum into two species - the eastern tiger salamanders are Ambystoma tigrinum, and the western populations are Ambystoma mavortium. The lack of uncertainy concerning the systematics of the group has also caused others to continue to use the traditional classification Ambystoma tigrinum.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Everson et al. (2021, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118: e2014719118) conducted rangewide sampling and presented genetic evidence from numerous nuclear loci that there are only two major lineages within this species. One of them corresponds to A. m. nebulosum, while limited evidence was found for the validity of the other described subspecies. They did not recommend taxonomic changes and Raffaëlli (2022, Salamanders & Newts of the World. Plumelec, Penclen) recognized all five subspecies, which we follow here."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Ambystoma tigrinum - Tiger Salamander (with subspecies)(Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Ambystoma tigrinum - Tiger Salamander (no subspecies) (Stebbins 2003)

Ambystoma tigrinum - Tiger Salamander (with subspecies) (Bishop 1943, Stebbins 1954, 1966, 1985)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

Exotic species such as A. mavortium can dramatically disrupt native species, including fish and California Tiger Salamanders.

This species has been introduced into isolated locations in California as the result of escaped or intentionally released larvae that were used as sport fishing bait. Selling Tiger Salamander larvae for fish bait is now illegal in California. Expanding irrigation in arid areas has aided their spread and it is likely that the salamanders have also wandered and inhabited new wetlands.

Ambystoma mavortium hybridizes with the California Tiger Salamander. This represents another very serious threat to that species which is already threatened by habitat loss, and introduced predators. Tiger Salamanders in the Salinas Valley are mostly hybrids that derived from intentional introductions of A. mavortium by the sport fishing bait industry. (Johnson et al., 2010)

All species of tiger salamanders are at threat from the continued alteration and destruction of wetlands, including introduced fishes. Deforestation and acidification of wetlands are also problems for some populations.

It is against the law to capture, move, possess, collect, or distribute this invasive species in California.

See: California Department of Fish and Game Restricted Species Regulations

|

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Ambystomatidae |

Mole Salamanders |

Gray, 1850 |

| Genus |

Ambystoma |

Mole Salamanders |

Tschudi, 1838 |

Species

|

mavortium |

Western Tiger Salamander |

Baird, 1850 “1849” |

|

Original Description |

Baird, 1850 - Journ. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Ser. 2, No. 1, p. 284 and p. 292

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Ambystoma - Greek - amblys = blunt + stoma = mouth

mavortium - Latin = war-like, referring to Mars, Roman god of war

(melanostictum - Greek = black spotted, referring to light spotting on dark dorsum)

(nebulosum - Latin = cloudy)

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Salamanders |

California Tiger Salamander

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Bishop, Sherman C. Handbook of Salamanders. Cornell University Press, 1943.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Petranka, James W. Salamanders of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution, 1998.

Jarrett R. Johnson, Robert C. Thomson, Steven J. Micheletti, H. Bradley Shaffer. The origin of tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) populations in California, Oregon, and Nevada: introductions or relicts? Conservation Genetics. Received: 19 November 2009 / Accepted: 19 September 2010.

Sam Sweet. SoCal Endangered species herping, part 2. FieldHerpForum. 2010

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

It is against the law to capture, move, possess, collect, or distribute this invasive species.

See: California Department of Fish and Game Restricted Species Regulations

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|

Red dots: some of the areas where populations of non-native

Red dots: some of the areas where populations of non-native