|

|

| Adult male, Trinity County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Calaveras County |

Adult female, Trinity County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male from Tule Lake, Siskiyou County |

Adult female, Siskiyou County |

Adult female, Siskiyou County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, El Dorado County |

Adult male, Siskiyou County |

Adult male, Siskiyou County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Humboldt County |

Adult female, Solano County |

Recent hatchling, August, Maury Island, King County, Washington

© Steven Caldwell

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Butte County |

Juvenile, Sierra County |

Adult, Lake County © Gary Beach |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Solano County |

Adult, Sonoma County |

Adult male, Tulare County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Merced County |

Del Norte County, © Alan Barron |

Adult female, Sutter County

© Jackson Shedd |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Siskiyou mountains, Siskiyou County |

Adult male, Sutter Buttes, Sutter County.

© Jackson Shedd.

Specimen courtesy of Eric Olson. |

Adult male, Sutter County

© Jackson Shedd |

|

|

|

|

| Dark phase adult male, Del Norte County |

Adult male, Trinity County |

|

|

|

|

Adult, in dark phase before warming up, Humboldt County © Dylan Gross

Sometimes fence lizards are very dark before they have warmed up in the sun. They can look like they're completely black at a distance.

|

Adult male, Sonoma County |

Adult male, Butte County,

defecating.

|

Juveniles, Stanislaus County © Joe Lovell |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Stanislaus County © Joe Lovell |

Adult female, Siskiyou County |

Adult female, Siskiyou County |

|

|

|

|

| This adult male intergrade or hybrid from Yosemite Valley in Mariposa County is extremely blue. © John Aylward, www.GreatOutdoorImages.com |

Adult female, Siskiyou County |

Two adult males squared off and showing each other their colors and bodies in a territorial dispute in Lake County. © Kathleen Scavone |

This adult male Northwestern Fence Lizard and adult male Greater Brown Skink were photographed basking together in Placer County in late April

© Rod |

|

|

|

|

| Adult female, Stanislaus County © Joe Lovell |

Western Fence Lizards have overlapping keeled scales with spines on them over much of their body. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Predation and Parasites |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile fence lizards are preyed upon by many other animals, including the black widow spider. © Rory Doolin |

Sean Kelly © shot this series of a California Striped Racer eating a male Great Basin Fence lizard in San Diego County. |

|

|

|

|

| California Striped Racers eat mostly lizards. This one is swallowing a Western Fence Lizard while holding the front third of its body straight up off the ground. This racer usually hunts with its head in this elevated position. |

Juvenile Pacific Gopher Snake eating a Western Fence Lizard © Daniel Harris |

A California Striped Racer swallows a male Northwestern Fence Lizard in

El Dorado County © Jim Bennett |

|

|

|

|

Adult male with ticks on the side of his head.

In California, western black-legged ticks (deer ticks) are the primary carriers of Lyme disease. Very tiny nymphal deer ticks are more likely to carry the disease than adults. A protein in the blood of Western Fence Lizards kills the bacterium in these nymphal ticks when they attach themselves to a lizard and ingest the lizard's blood. This could explain why Lyme disease is less common in California than it is in some areas such as the Northeastern states, where it is epidemic.

More Information

|

Sean Kelly found this juvenile Southwestern Speckled Rattlesnake eating a Great Basin Fence Lizard behind his garbage can one afternoon in San Diego County.

© Sean Kelly |

|

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Mendocino County |

Habitat, El Dorado County |

Habitat, Calaveras County |

Habitat, Shasta County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Smith River, Del Norte County |

Habitat, lava beds, Siskiyou County |

Habitat, Butte County |

Habitat, Trinity County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Solono County |

Habitat, Siskiyou County |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

A California Western Fence Lizard Travels to Germany

|

|

|

|

|

The lizard shown directly above was found in a freight container containing only metal boxes at the BMW plant in Dingolfing / Bavaria / Germany on Oct 17, 2006. The container was shipped from Stockton CA on Sep 14, 2006. The lizard survived a 33 day voyage without food and water. The container was placed most likely on the top deck of the vessel and hence cooled down considerably at night which explains the good condition of the animal upon arrival.

Photos © Jochen Späth

Information: Guntram Deichsel

Many species of plants and animals have been introduced into areas of the planet where they did not naturally evolve. The journey of this lizard illustrates one way animals can spread around the globe: If the lizard was a gravid female who found conditions favorable to her survival once she arrived, laid her eggs, and eventually the offspring began reproducing, or if other lizards arrived at the same location and bred with her, then an established breeding population could develop. |

| |

| Short Videos of Northwestern Fence Lizards |

|

|

|

|

| A male Northwestern Fence Lizard defecates off the side of a Butte County fence, wipes himself off, then does a territorial push-up display. |

I'm not going out of my way trying to film this behavior - I can only take what I get - so here we see another Northwestern Fence Lizard doing his business for the camera. It's like they're trying to tell me something. |

These two videos show a Placer County Northwestern Fence Lizard appearing to taunt a garter snake (a Mountain Gartersnake is my guess, because it lacks red.) The lizard keeps moving down towards the snake but when the snake moves towards the lizard, apparently trying to catch it for dinner, the lizard runs up the wall away from the snake. © Rod |

|

|

|

|

| A male Northwestern Fence Lizard fights with a female in Placer County. © Rod |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos of Other Subspecies of Western Fence Lizard |

|

|

|

|

| Sierra Fence lizards run around a rocky area in the woods 8,000 ft. high in the Sierra Nevada mountains. |

A Sierra Fence Lizard, or intergrade, runs around rocks in the forest up at 5,600 ft. in Tuolumne County. |

A male fence lizard in Inyo County defensively showing his throat color and doing push-ups. |

San Joaquin Fence Lizards on trees along a river in early spring. |

|

|

|

|

| A few fence lizards in Contra Costa County. |

A male fence lizard on a tree in Alameda County. |

Several juvenile fence lizards come out to bask in the sun on a cool and windy morning in early March. |

Two Coast Range Fence Lizards, Sceloporus occidentalis bocourtii, are observed during the breeding season in early May in San Benito County. The first lizard, a female, has moved from her perch on a rock to a nearby rock in order to get away from the photographer. She begins a territorial push-up display when a male comes up the side of the rock and begins to pursue her. She arches her back and hops away in order to reject him. She may have already mated and is bearing eggs, or maybe he is not her type. He finally stops and does a push-up display, possibly to continue trying to entice her, or possibly to warn the photographer that this is his territory.

|

|

|

|

|

| A female fence lizard runs across a wall in Riverside County and encounters a male who pursues her. She rejects him and he runs to an open spot on top of the wall and does a push-up display. |

Large, dark phase Great Basin Fence Lizards bask and eat ants off rocks in Inyo County.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

2.25 - 3.5 inches long from snout to vent (5.7 - 8.9 cm). (Stebbins 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A fairly small lizard with large overlapping keeled scales with spines on them on the back and sides.

Scales on the backs of the thighs are mostly keeled. |

| Color and Pattern |

Color is brown, gray, or black with blotches.

Sometimes light markings on the sides of the backs form stripes or irregular lines, and sometimes dark blotching may form irregular bands.

The rear of the limbs is yellow or orange.

The base color of the throat and underside are typically pale to dark gray and sometimes black. |

| Male / Female Differences |

Males have blue markings on the sides of the belly edged in black, two blue patches on the throat, often connected with a light band, enlarged post-anals,

enlarged femoral pores, and a swollen tail base.

On some males the throat and dorsal coloring around the bright blue can be very dark.

Some scales on a male's back and tail become blue or greenish when he is in the light phase.

Females have faint or absent blue markings on the belly, no blue or green color on the upper surfaces, and dark bars or crescents on the back. |

| Young |

Juveniles have little or no blue on the throat and faint blue belly markings or none at all.

|

| |

| Differences Between the Western Fence Lizard and the Similar Sagebrush Lizard in California |

| |

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Diurnal.

Often seen basking in the sun on rocks, downed logs, trees, fences, and walls.

Prefers open sunny areas.

Active when temperatures are warm, becomes inactive during periods of extreme heat or cold, when they shelter in crevices and burrows, or under rocks, boards, tree bark, etc.

Common and easily encountered in the right habitat.

This is probably the species of lizard most often seen in the state due to its abundance in and near populated areas and its conspicuous behavior.

|

| Territoriality |

Males establish and defend a territory containing elevated perches where they can observe mates and potential rival males.

Males defend their territory and try to attract females with head-bobbing and a push-up display that exposes the blue throat and ventral colors. Territories are ultimately defended by physical combat with other males. |

| Defense |

The tail can break off easily, but it will grow back.

The detached tail wriggles on the ground which can distract a predator from the body of the lizard allowing it time to escape.

More information about tail loss and regeneration. |

| Diet and Feeding |

| Eats small, mostly terrestrial, invertebrates such as crickets, spiders, ticks, and scorpions, and occasionally eats small lizards including its own species. |

| Reproduction |

Adults breed in the spring of their second year.

Courtship and mating take place from late April to early June.

Egg laying occurs 2 - 4 weeks after copulation, usually from June to July.

Females lay 1-3 clutches of

3 - 17 eggs (averaging 8) in a season.

Females dig small pits in loose damp soil (often at night) where they lay the eggs.

Eggs have white leathery shells and measure 8 by 14 mm.

Eggs hatch in about 60 days, usually from July to September.

(Stebbins, 2003; Nussbaum et al, 1983)

|

| Western Fence Lizards and Lyme Disease |

In California, western black-legged ticks (deer ticks) are the primary carriers of Lyme disease. Very tiny nymphal deer ticks are more likely to carry the disease than adults. A protein in the blood of Western Fence Lizards kills the bacterium in these nymphal ticks when they attach themselves to a lizard and ingest the lizard's blood. This could explain why Lyme disease is less common in California than it is in some areas such as the Northeastern states, where it is epidemic.

More Information: (Berkeleyan April 1998)

In an interesting twist, UC Berkeley researchers have found that when fence lizards are removed from an area, the population of Lyme disease-carrying ticks plummets. Up to 90 percent of juvenile Western black-legged ticks, the species that carries the Lyme disease bacteria, feed on Western Fence Lizards. When lizards are no longer available, 95 percent of the ticks fail to find another host to feed on.

More Information: (Berkeley News February 2011)

|

| Habitat |

Found in a wide variety of open, sunny habitats, including woodlands, grasslands, scrub, chparral, forests, along waterways, suburban dwellings, where there are suitable basking and perching sites, including fences, walls, woodpiles, piles of rocks and rocky outcrops, dead and downed trees, wood rat nests, road berms, and open trail edges.

|

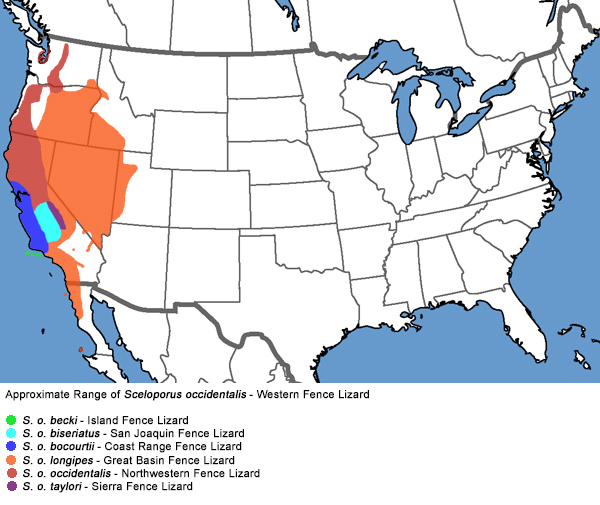

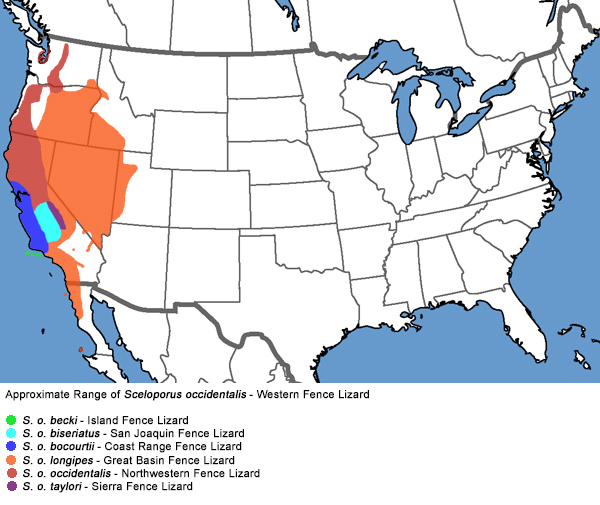

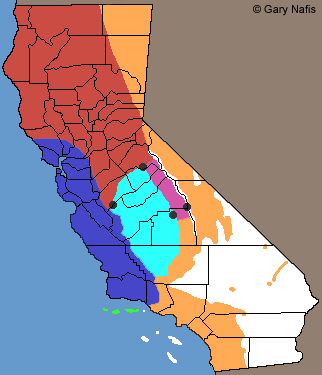

| Geographical Range |

This subspecies ranges from north and east of the San Francisco Bay Area north into Oregon, and Washington.

The species Sceloporus occidentalis ranges from northern Baja California north to Washington and east to Idaho, Nevada and Utah.

Several Western Fence Lizards have been found in British Columbia. They could have been transported by human activity or they could be escaped pets, but their proximity to native populations in northwest Washington State could also indicate a natural origin.

* (Farrell, R., G. Hanke, and D. Veljacic. 2020. First verified sighting of a Western Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis) in British Columbia, Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 134(3): 210–212. https://doi.org/10.22621/cfn.v134i3.2571)

The ranges of subspecies shown on the range map above are based mostly on Ryan Calsbeek's distribution map.

|

|

An alternate interpretation of the ranges of S. o. longipes and S. o. occidentalis showing S. o. occidentalis present in northeastern California and central Oregon instead of S. o. longipes can be seen here.

|

| Elevational Range |

The species Sceloporus occidentalis - Western Fence Lizard, is found at elevations from sea level to around 10,800 ft.

(3,300 m.) (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

The taxonomy of Sceloporus occidentalis needs to be studied further. Six subspecies have been traditionally recognized based on geographic variation in morphology, but molecular studies have identified four major clades and eleven different genetic groups in California (James Archie, Cal State University Long Beach). The current taxonomy does not correspond with the ongoing research, so it is certain that in the future the current subspecies and their ranges will be completely revised, probably with several new species described. For this reason some experts no longer recognize any subspecies of S. occidentalis pending further studies.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The 2017 SSAR Names List removed the subspecies S. o. taylori and now shows only five subspecies, but many authorities have already accepted research that concludes that S. o. becki, the Island Fence Lizard, is a unique species - Sceloporus becki (Wiens & Reeder, 1997) (Bell, 2001) which would leave only four subspecies of S. occidentalis.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The 2025 SSAR Names List recognizes 4 subspecies of S. occidentalis and recognizes S. becki as a full species. But they don't give scientific or common names to two of the subspecies, so once again the choices are to leave the four subspecies as they have been for a long time, or to stop recognizing subspecies, which does not show the diversity within the species, so I choose to leave things as they are. For now.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"Bouzid et al. (2022, Molecular Ecology 31: 620–631) used RADseq data to characterize genetic structure and gene flow throughout the range of S. occidentalis. They found evidence for four or five populations inhabiting different geographic regions with admixture at the boundaries between them. They inferred long-term stability in the southern portions of the range and northward expansion followed by secondary contact in the north and suggested that S. occidentalis constitutes an ephemeral ring species. The authors did not address taxonomy, but their results indicate that the current subspecies taxonomy (e.g., Bell and Price, 1996, Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 631.1) needs revision.

S. o. occidentalis corresponds approximately to the Pacific Northwest population.

S. o. biseriatus and S. o. bocourti are part of a single population (central California west of the Sierra Nevada), for which the name S. o. biseriatus has priority.

The former S. o. longipes is composed of an eastern Sierra Nevada population and a Great Basin population, which were sometimes inferred to form a single population and a separate Southern California population.

We here treat the combined Great Basin and eastern Sierra Nevada population as one subspecies and the Southern California population as another; however, this creates nomenclatural complications because specimens from near the type locality of S. o. longipes are not assigned to any of these populations, and it is unclear if there are any available names for them (e.g., S. smaragdinus Cope, in Yarrow, 1875 is based on specimens from the Great Basin but is unavailable as a junior primary homonym of S. smaragdinus Bocourt, 1873 [Bell et al., 2003, Acta Zoológica Mexicana. 90: 103–174]; S. biseriatus nigroventris Bocourt, 1874 is based on one or more specimens from “Californie”, whose precise collection locality is currently unknown). The taxonomy of S. occidentalis needs further study."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Commonly called: Bluebelly, Blue-bellied Lizard, Fence Lizard, Swift, Fence Swift

Sceloporus occidentalis - Western Fence Lizard (no subspecies recognized) (Stebbins 2003, 2012, 2018)

Sceloporus occidentalis occidentalis - Northwestern Fence Lizard (Stebbins 1966, 1985)

Sceloporus occidentalis occidentalis - Pacific Fence Lizard (Smith 1946)

Scelopoorus occidentalis occidentalis - Pacific Blue-bellied Lizard (Sceloporus undulatus var. bocourtii, part; Sceloporus frontalis; Sceloporus undulatus occidentalis, part; Scelopus undulatus undulatus, part; Sceloporus undulatus thayeri, part. Western Fence Lizard; Western Alligator Lizard, part; Pacific Swift; Thayer's Alligator Lizard; Alligator Lizard, part.) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| None |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Phrynosomatidae |

Zebra-tailed, Earless, Fringe-toed, Spiny, Tree, Side-blotched, and Horned Lizards |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Genus |

Sceloporus |

Spiny Lizards |

Wiegmann, 1828 |

| Species |

occidentalis |

Western Fence Lizard |

Baird and Girard, 1852 |

Subspecies

|

occidentalis |

Northwestern Fence Lizard |

Baird and Girard, 1852 |

|

Original Description |

Sceloporus occidentalis - Baird and Girard, 1852 - Prox. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 6, p. 175

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Sceloporus - Greek - skelos = leg + porus = pore or opening - refers to the femoral pores on hind legs

occidentalis - Latin = western - refers to its distribution in western North America.

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Lizards |

Western Fence Lizards:

Sceloporus becki - Island Fence Lizard

Sceloporus occidentalis biseriatus - San Joaquin Fence Lizard

Sceloporus occidentalis bocourtii - Coast Range Fence Lizard

Sceloporus occidentalis longipes - Great Basin Fence Lizard

Sceloporus occidentalis taylori - Sierra Fence Lizard

Sagegrush Lizards:

S. graciosus graciosus - Northern Sagebrush Lizard

S. graciosus gracilis - Western Sagebrush Lizard

S. vandenburgianus - Southern Sagebrush Lizard

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Jones, Lawrence, Rob Lovich, editors. Lizards of the American Southwest: A Photographic Field Guide. Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2009.

Smith, Hobart M. Handbook of Lizards, Lizards of the United States and of Canada. Cornell University Press, 1946.

Brown et. al. Reptiles of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society,1995.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow,

Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

St. John, Alan D. Reptiles of the Northwest: Alaska to California; Rockies to the Coast. 2nd Edition - Revised & Updated. Lone Pine Publishing, 2021.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

Wiens & Reeder (1997 Herpetological Monographs 11: 1-101)

Bell (2001 Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 37(4): 137-142)

S. Morey. Western Fence Lizard Family: Phrynosomatidae R022. California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Game. Originally published in Zeiner, D.C., W.F.Laudenslayer, Jr., K.E. Mayer, and M. White, eds. 1988-1990.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This animal is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

Red: Range of this subspecies in California

Red: Range of this subspecies in California