|

|

|

|

| Adult, Inyo County |

Adult, Inyo County |

Adult, Inyo County |

|

|

|

| Adult, Inyo County © Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

Adult, Mono County.

© Ceal Klingler |

Adult, Mono County, using nictitating membrane to moisten eyes.

© Ceal Klingler

|

Adult female (left) & Adult male (right) Inyo County © Adam Clause |

|

|

|

| Adult male, Inyo County © Adam Clause |

Adult male, Mono County

© Adam Clause |

A small hardened black "spade" on each rear foot helps with digging and gives the "spadefoot" family of frogs its name. |

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Mono County © Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Mono County © Ryan Sikola |

Adult male, Inyo County

© Richard Porter |

|

| |

|

|

| Great Basin Spadefoots From Outside California |

|

|

|

| |

Adult, Franklin County, Washington |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Franklin County, Washington |

Adult, Franklin County, Washington |

Adult, Franklin County, Washington

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Mineral County, Nevada |

Underside of adult,

Franklin County, Washington |

Adult, Franklin County, Washington |

| |

|

|

| Reproduction, Eggs, Tadpoles, and Young |

|

|

|

Male calling at night,

Grant County, Washington |

Male calling at night,

Grant County, Washington |

Male calling at night,

Grant County, Washington |

|

|

|

| Two mature eggs attached to a stick which was found submerged in shallow water in an irrigation ditch. |

Mature tadpole |

Recently-transformed juvenile |

More pictures of developing Great Basin Spadefoot tadpoles.

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

Habitat, dry wash, Deep Springs Valley, Inyo County (early June 2003)

One night in early July of 1999, this dry desert wash was full of water from recent rains and Great Basin Spadefoots were calling from the water and moving about on the valley floor. |

Habitat, Inyo County |

Breeding pond,

Grant County, Washington |

| |

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

| One night while searching for spadefoot choruses to record, we discovered a spadefoot crossing a gravel road. After we picked it up and moved it to the sand for photographs, it began to slowly bury itself. It took about 5 minutes to completely bury itself, but that has been cut down to about a minute here. |

Male spadefoots call at night from a shallow stagnant pool in central Washington.

(Short Version) |

Male spadefoots call at night from a shallow stagnant pool in central Washington.

(Long Version) |

| |

|

|

| |

As they sat around their campsite in the Nevada desert, a group of herpetology students suddenly saw this spadefoot dig itself out of the sand. Maybe the vibrations on the ground from the people moving about felt like a sudden heavy rain and stimulated it to emerge. This short movie shows the spadefoot digging back into the sandy soil and burying itself. © Julie Nelson |

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 1.5 - 2.5 inches long from snout to vent (3.8 - 6.3 cm).

|

| Appearance |

A small stout-bodied toad with short legs and warty skin.

There is a glandular bump between the eyes and a dark spot on each eyelid.

A glossy black spade shaped like a wedge is present on each hind foot.

Parotoid glands are not present.

|

| Color and Pattern |

Gray-green to olive above, with light stripes on the sides on the back,

and brownish or reddish spots at the tips of skin tubercles.

Whitish below.

Eyes are gold with vertical pupils. |

| Larvae (Tadpoles) |

Tadpoles are dark brown - black above, golden below, with the eyes set in from the margin of the head, and grow up to 2.75 inches long (7 cm.)

|

| Life History and Behavior |

| Activity |

Nocturnal. Juveniles may feed during the day.

Almost completely terrestrial, entering water only to breed.

Spends 7 - 8 months of its life buried underground in deep burrows during the winter cold and in shallow burrows curing summer dry periods.

Spades on hind feet assist in digging burrows in the soil.

Mammal are also used for refuge.

Great Basin Spadefoots are active on the surface at night after rains or during periods of agricultural irrigation. |

| Defense |

| Noxious skin secretions probaby repulse predators, and can cause burning and allergic-type reactions in humans. |

Territoriality

|

| There is little evidence of territorial behavior. |

| Longevity |

| Unknown. Tinsley and Tocque (1995) estimated that females live about 13 years and males about 11 years in the wild. |

| Voice (Listen) |

Calls are made at night.

The call is a loud short 1-3 note duck-like snoring sound, which has been compared to the sound of a flock of ducks slowed down. |

| Diet and Feeding |

| Diet consists of a wide variety of invertebrates, much of which is ants. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Fertilization is external, with the male grasping the back of the female and releasing sperm as the female lays her eggs.

The reproductive cycle is similar to that of most North American Frogs and Toads. Mature adults come into breeding condition and the males call to advertise their fitness to competing males and to females. Males and females pair up in amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Males probably become reproductively mature the first or second year after metamorphosis, and females in the second year.

Breeding takes place spring through summer (mostly April through July) depending on the location, in permanent and temporary pools, lakeshores, ponds, stock tanks, at the edges of agricultural fields, and irrigation ditches. East of the Sierra Nevada, where there is little rainfall or snowmelt to create temporary pools, breeding occurs in overflow pools of permanent streams and in springs.

Adults move from winter refuges to breeding sites when temperatures warm up, typically beginning in April, and it has been estimated they can travel as far as 5 km.

Rainfall can stimulate breeding, but it is not always necessary. Irrigation waters can stimulate breeding also.

Breeding does not necessarily occur at the same time each year at a location.

Breeding pools must remain filled for at least 40 days in order for larvae to successfully transform.

|

| Eggs |

Females lay anywhere from 300 to 1000 eggs in small grape to plum-sized clusters of 20 - 40 eggs, which are attached to floating sticks and underwater vegetation.

Eggs hatch after 2 - 4 days. |

| Tadpoles and Young |

Tadpoles transform in about 47 days, ranging from 36 - 60 days.

Transformed juveniles move onto land temporarily before their tail has been fully absorbed.

Once metamorphosis is complete, they remain at the breeding site for a few days to several weeks before they travel away from the site.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits arid regions of sagebrush flats, bunch grass prairie, arid shrublands, and open forests with sandy soil.

|

| Geographical Range |

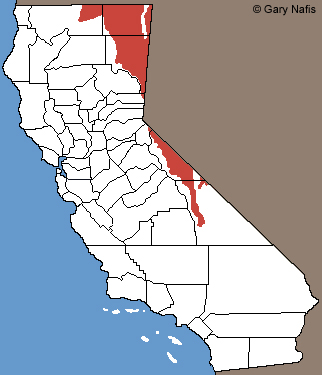

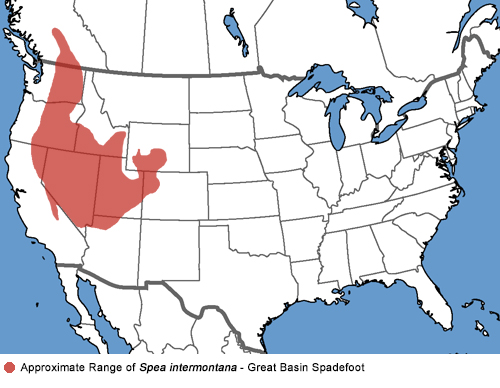

In California this spadefoot is found in the Great Basin region east of the Sierras from the northern Owens Valley, north through the northeast corner of the state.

The species is found to the north of California, east of the Cascades mountains, through Oregon and Washington, into southern British Columbia, and east of California through southern Idaho and Wyoming, Utah, northeast Colorado, most of Nevada, and northwest Arizona.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Up to 9,200 ft. (2800 m).

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Before being assigned to the genus Spea, this spadefoot was known as Scaphiopus intermontana.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List comments:

"There is considerable inconsistency in the older literature regarding this taxon and both S. multiplicata and S. hammondii.

"Neal et al., 2018 (Conservation Genet- ics 19: 937–946), using nDNA and mtDNA recovered two distinct clades (“Oregon” and “California”), with the “Oregon” clade being sister to S. bombifrons and support for the California clade recovered as sister to the Southern clade of S. hammondii."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Spea intermontana - Great Basin Spadefoot (Stebbins 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012))

Scaphiopus intermontanus - Great Basin Spadefoot (Stebbins 1966, 1985)

Scaphiopus hammondii intermontanus - Great Basin Spadefoot Toad (Western Spadefoot Toad) (Wright & Wright 1949)

Scaphiopus hammondii - Western Spadefoot Toad (Storer 1925)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| While Great Basin Spadefoots are extirpated in areas where agriculture and urbanization have destroyed their habitat, they have also colonized new areas where artificial water sources create new breeding sites. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Pelobatidae |

Spadefoot Toads and Relatives |

Cope, 1865 |

| Genus |

Spea |

Western Spadefoots |

Cope, 1866 |

| Species |

intermontana |

Great Basin Spadefoot

|

(Cope, 1883) |

|

Original Description |

(Cope, 1883) - Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 35, p. 15

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Spea - Greek - speos = cave, cavern

intermontana - refers to the Great Basin locality (the area between the mountains):

Latin - inter = between

Latin -

montis = mountain

Latin - anus = belonging to

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Frogs |

Scaphiopus couchii

Spea hammondii

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Degenhardt, William G., Charles W. Painter, & Andrew H. Price. Amphibians and Reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

Williamson, Michael A., Paul W. Hyder, & John S. Applegarth. Snakes, Lizards, Turtles, Frogs, Toads & Salamanders of New Mexico. Sunstone Press, 1994.

Corkran, Charlotte & Chris Thoms. Amphibians of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, 1996.

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

Leonard et. al. Amphibians of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, 1993.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Elliott, Lang, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. Frogs and Toads of North America, a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of California Press Berkeley, California 1925.

Wright, Albert Hazen and Anna Wright. Handbook of Frogs and Toads of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1949.

Davidson, Carlos. Booklet to the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast - Vanishing Voices. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 1995.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This Spadefoot is not included on the Special Animals List, meaning there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California according to the California Department of Fish and Game.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

|

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

|

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

|

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

|

|

| USDA Forest Service |

|

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|

|