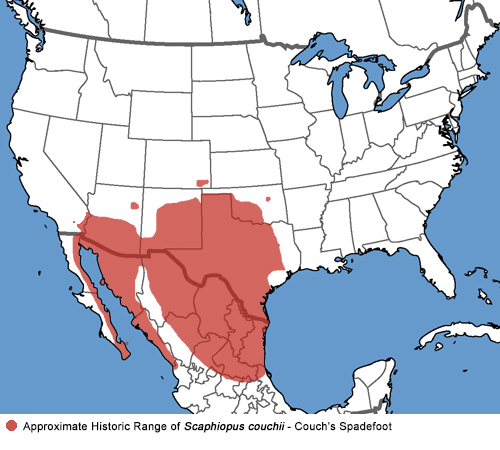

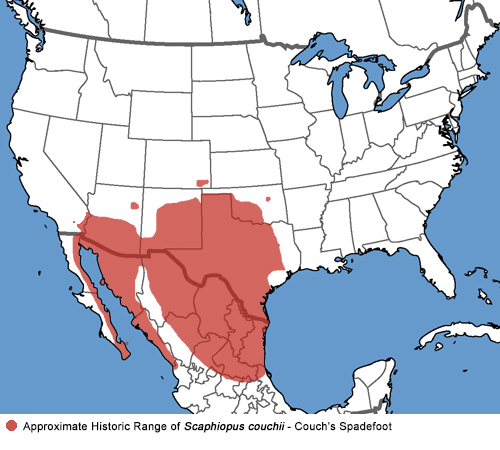

Red:

Red: Range in California

(Distribution is fragmented within the red areas.)

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

Listen to this spadefoot:

A short example

|

| Couch's Spadefoots From California |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Imperial County

© August 2004 William Flaxington

|

Adult, Imperial County

© August 2004 William Flaxington |

Adult, Imperial County © Julie Stout

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Riverside County desert,

active after tropical storm Hillary dumped record amounts of rain on the desert in August 2023 © Ryan Sikola |

Juvenile, Riverside County desert,

active after tropical storm Hillary dumped record amounts of rain on the desert in August 2023 © Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Riverside County

© Zachary Cava |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

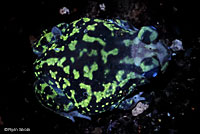

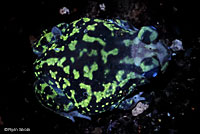

| Couch's Spadefoot photographed in ultraviolet light at night |

|

|

|

|

Top - Adult in normal light

Bottom - Adult in untraviolet light

Riverside County, 8/23 © Ryan Sikola |

Adult, Riverside County desert, 8/23 © Ryan Sikola |

| |

|

|

|

| Couch's Spadefoots From Outside California |

|

|

|

|

| Adult female, Pima County, Arizona |

Adult male, Yuma County, Arizona |

Adult, Pima County, Arizona

|

|

|

|

|

| Digging spade on hind foot |

A small hardened black "spade" on each rear foot helps with digging and gives the "spadefoot" family of frogs its name. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Mating Adults |

|

|

|

|

Adult Male (top) in amplexus with Adult Female (bottom), Brewster County, Texas.

In these spadefoots, amplexus is inguinal - the male clasps the female around her pelvis, unlike most of our frogs which use axial amplexus - the male grasps the female around her forelimbs. |

Adult males calling at night while floating on water, Brewster County, Texas |

|

|

|

|

Adult male calling at night,

Brewster County, Texas |

Male and female in amplexus, and a solo male, Pima County, Arizona |

Male and female in amplexus,

Pima County, Arizona |

Male and female in amplexus,

Pima County, Arizona |

|

|

|

|

Male at night in breeding pond,

Pima County, Arizona |

Male at night in breeding pond,

Pima County, Arizona |

Male at night in breeding pond,

Pima County, Arizona |

|

| |

|

|

|

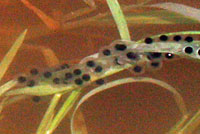

| Eggs and Tadpoles |

|

|

|

|

| Eggs laid on grass in shallow water |

Recently-hatched tadpole,

Yuma County, Arizona |

Recently-hatched tadpole, Yuma County, Arizona |

| |

|

|

|

| California Habitat |

|

|

|

|

Agricultural habitat, Riverside County

© August 2004 William Flaxington

|

Habitat, rain pool in desert wash, Imperial County © August 2004

William Flaxington |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Habitat Outside California |

|

|

|

|

| A breeding pool in a flooded wash, Pima County, Arizona. The night before this picture was taken, dozens of calling male Couch's Spadefoots lined the banks. |

A breeding pool in a flooded wash, Pima County, Arizona |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, pools adjacent to an agricultural field, Yuma County, Arizona |

Breeding Habitat,

Brewster County, Texas |

Breeding habitat, Brewster County,Texas

This rain pool formed quickly one afternoon during a heavy thunderstorm. Several Couch's Spadefoots quickly appeared in it and began calling. |

|

| |

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

Male spadefoots call at night from a temporary rain pool.

|

Male and female spadefoots in amplexus in a temporary rain pool. |

A group of adult males at night in a breeding pond in Arizona swim around harassing each other. Other male Couch's Spadefoots are calling in the background along with some Lowland Burrowing Treefrogs. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 2.25 - 3.6 inches long from snout to vent (5.7 - 9.1 cm).

|

| Appearance |

A small stout-bodied toad with short legs and warty skin.

The eyes are wide-set with no boss in-between.

Pupils are vertical.

A hard black sharp-edged spade shaped like a sickle is found on each hind foot.

Parotoid glands are not present. |

| Color and Pattern |

Variable in color and pattern, from greenish or brownish yellow to bright green above, with a network of irregular dark markings, or black flecking.

Whitish below. |

| Male/Female Differences |

Males tend to be greener than females with fewer

markings. |

| Larvae (Tadpoles) |

Tadpoles are an iridescent coppery bronze with golden spots or sheen.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

| Activity |

Nocturnal. Newly-transformed juveniles are also active in daylight.

Terrestrial - spending most of its life (around 8 - 10 months each year) buried in the ground, and emerging briefly only during spring and summer rains. Low frequency sounds and vibrations caused by rainfall and thunder apparently stimulate emergence from the soil, rather than soil saturation. The location of refuge burrows is not known, but it is not thought to be in soil underneath dried up breeding pools.

S. couchii is more adapted to extremely dry conditions than any other North American amphibian, remaining underground without emerging for as many as two rainless summers.

During the summer, when rain allows surface activity, adults spend days and dry nights in shallow burrows that they dig themselves.

An individual spadefoot digs backwards into the soil using the spades on the hind feet. |

| Defense |

| S. couchii releases irritating skin secretions which probably deters predators. These secretions can cause sneezing, running nose, and watery eyes in humans, and extreme irritation if rubbed into the nose or eyes. (After handling a spadefoot then barely touching my eye, the eye swelled up and the other eye watered so badly I was unable to see well for about an hour. Wash your hands very well after handling this spadefoot!) |

Territoriality

|

| There is little evidence of territorial behavior. |

| Longevity |

| Longevity is estimated to be up to 11 years for males and 13 years for females. |

| Voice (Listen) |

A loud nasal groan descending in pitch similar to a lamb bleating.

Calls are made at night from the edge of temporary ponds. |

| Diet and Feeding |

| Eats a variety of invertebrates, many of which are winged and larval termites which also emerge during rains. Beetles, ants, grasshoppers, spiders, and crickets are also eaten. S. couchii can consume up to 55 percent of their body weight, which can be enough food to last a full year. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Fertilization is external, with the male grasping the back of the female and releasing sperm as the female lays her eggs.

The reproductive cycle is similar to that of most North American Frogs and Toads. Mature adults come into breeding condition and the males call to advertise their fitness to competing males and to females. Males and females pair up in amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Breeding adults are estimated to be from 2 - 10 years old.

Couch's Spadefoots breed explosively during times when scarce desert rainfall creates temporary pools from May through September. Most breeding occurs during the first night after pools form. Adults move up from underground hiding places and travel to the pool where males begin calling while floating on the water. Temporary pools are often in rocky streambeds, washes, at the edges of agricultural fields, in depressions beside roads and railroad tracks, and cattle tanks. In order for the eggs to hatch and larvae to successfully transform, the water needs to remain for a minimum of 7 - 8 days.

(One late afternoon in June in Alpine Texas, as a heavy thunderstorm moved through the area, I watched a dry grassy spot that looked like it had not see rain in months slowly fill with rainwater. In less than an hour after the heavy rain began, when it was still daylight, several male Couch's Spadefoots had emerged and were calling loudly from the shallow water. They called throughout the night. By the morning they were silent.) |

| Eggs |

Females lay a clutch of more than 3,000 eggs, which hatch in less than a day, and tadpoles transform faster than any other North American anurans - in about 7 or 8 days. The duration can depend on the duration of the pool and the food source. Tadpoles will sometimes remain in long-lasting pools, growing very large before they transform.

In California, larvae have been observed entering metamorphosis in 7.5 - 8.5 days.

At a location in West Texas, larvae transformed in 8-16 days.

|

| Tadpoles and Young |

Metamorphosed juveniles remain at the breeding pool for a few days, then move into nearby vegetation until the soil dries up, when they burrow into the ground or take refuge in cracks or holes. They emerge, along with adults on rainy nights, to feed, until they enter a permanent refuge for the dry season.

|

| Habitat |

Desert and arid regions of grassland, prairie, mesquite, creosote bush, thorn forest, sandy washes, agricultural ditches.

|

| Geographical Range |

In California, this spadefoot occurs in scattered populations east of the Algodones sand dunes in Imperial county, north into San Bernardino county at Chemihuevi Wash, and near the Salton Sea.

Overall, the species occurs from central Texas and southwest Oklahoma, west through north-central New Mexico and south-central Arizona, to extreme southeast California, and south to the southern tip of the Baja peninsula.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

From sea level to 5900 ft. elevation (1800 m).

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Scaphiopus couchii - Couch's Spadefoot (Stebbins 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Scaphiopus couchii - Couch Spadefoot (Stebbins 1985)

Scaphiopus couchi - Couch's Spadefoot (Stebbins 1954, 1966)

Scaphiopus couchii - Couch's Spadefoot (Southern Spadefoot, Rain Toad, Sonoran Spadefoot, Sonora Spadefoot, Cape St. Lucas Spadefoot) (Wright & Wright 1949)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

A California Species of Special Concern.

Protected from take with a sport fishing license in 2013.

Couch's Spadefoot toads are absent from former habitat which has been urbanized or converted to agriculture. But they persist throughout their small range in California. Road and railroad construction and probably agricultural irrigation have increased the number of temporary pools that can be used.

"The relatively fragmented nature of this species' California distribution and the physiological conditions under which it lives make it susceptible to localized extirpations due to habitat modification that destroys temporary pools and due to the effets of climate change."

"Off-highway vehicle usage in the Algodones Dunes has degraded habitat in many areas."

"Temporary and permanent anthropogenic water sources associated with livestock (cattle ponds) and perhaps agriculture may help to provide suitable breeding habitat that is important to the persistence of this species."

(Thompson et al, California Amphibian and Reptile Species of Special Concern, 2016.)

|

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Pelobatidae |

Spadefoot Toads and Relatives |

Cope, 1865 |

| Genus |

Scaphiopus |

North American Spadefoots |

Holbrook, 1836 |

| Species |

couchii |

Couch's Spadefoot

|

Baird, 1854 |

|

Original Description |

Baird, 1854 - Proc. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Vol. 7, p. 62

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

Eponyms

First described by Baird in 1854, the specific name "Scaphiopus couchii" and the common name "Couch's Spadefoot" honor Darius Nash Couch (1822-1897), an American soldier, businessman, and naturalist who collected the first specimen in northern Mexico.

See: Biographies of Persons Honored in the Herpetological Nomenclature © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Scaphiopus - Greek - skaphis = shovel or spade + Greek - pous = foot -- refers to the shape and adaptation of hind foot with a hard black spade used for digging

couchii - honors Couch, Darius N.

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Frogs |

Spea hammondii

Spea intermontana

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Degenhardt, William G., Charles W. Painter, & Andrew H. Price. Amphibians and Reptiles of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, 1996.

Williamson, Michael A., Paul W. Hyder, & John S. Applegarth. Snakes, Lizards, Turtles, Frogs, Toads & Salamanders of New Mexico. Sunstone Press, 1994.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Elliott, Lang, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. Frogs and Toads of North America, a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of California Press Berkeley, California 1925.

Wright, Albert Hazen and Anna Wright. Handbook of Frogs and Toads of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1949.

Davidson, Carlos. Booklet to the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast - Vanishing Voices. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 1995.

Robert C. Thompson, Amber N. Wright, and H. Bradley Shaffer. California Amphibian and Reptile Species of Special Concern. California Department of Fish and Wildlife. University of California Press, 2016.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G5 |

Secure—Common; widespread and abundant. |

| NatureServe State Ranking |

S2 |

Imperiled in the state because of rarity due to very restricted range, very few populations (often 20 or fewer), steep declines, or other factors making it very vulnerable to extirpation from the state.

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

SSC |

California Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management |

S |

Sensitive |

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

LC |

Least Concern |

|

|

|