|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, San Bernardino County |

Sub-adult, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult crossing a road in the late afternoon, San Bernardino County |

Old adult out on a trail in the afternoon, Riverside County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, San Bernardino County, in defensive pose. |

Adult, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

|

| Captive adult © Gary Nafis Specimen courtesy of Ed Pirog (S.T.F.U.) |

|

|

|

|

| Adult in burrow, San Bernardino County © Jeff Ahrens |

Adult in burrow, San Bernardino County © Jeff Ahrens |

Adult in burrow, San Bernardino County © Jeff Ahrens |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, Kern County © Lou Silva |

Adult male emerging from burrow,

Kern County © Lou Silva |

Adult male, Kern County © Lou Silva |

Adult, San Bernardino County

© Bill Ford |

|

|

|

|

| Adult eating, Riverside County © Emily Mastrelli |

This San Bernardino County adult tortoise was found stuck on some small rocks. It could not touch the ground with its front legs or push off with its back legs, though it probably would have worked itself free eventually. When a rock was removed, it was able to continue on its way. © Jeff Ahrens |

|

|

|

|

Dry shells from expired tortoises, San Bernardino County © Jeff Ahrens

|

|

|

|

|

Adult, Riverside County

© Terry Goyan |

Adult, Riverside County

© Terry Goyan |

Adult from the introduced population in Anza-Borrego State Park, San Diego County. © Jeff Nordland |

Adult, San Bernardino County

© Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

|

|

|

|

© Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg

This Riverside County adult is a longterm (wild) study animal that USGS researchers have named "Shirley." She has been observed traveling between a burrow in a wash and a burrow 1000 feet higher up a cliff, in less than a day.

|

Ravens are known to prey on hatchling Desert Tortoises. The birds are natural desert residents, but their numbers have been increasing due the increased amount of food available in the garbage from the human settlements which have steadily encroached onto tortoise habitat. The spikes placed on top of these fence poles illustrate one of the methods used to discourage ravens from roosting near protected tortoise habitat. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

This San Bernardino County hatchling is barely an inch and a half wide.

© Kenny Paul |

Captive juvenile © Gary Nafis Specimen courtesy of Ed Pirog (S.T.F.U.) |

|

|

|

|

| Hatchling, rescued from raven predation, San Bernardino County © Bill Ford |

Hatchling with U.S. quarter dollar coin for size comparison, San Bernardino County © Aaron Wells |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Mating Season |

|

|

|

|

| Mating male and female in San Bernardino County © Emily Mastrelli |

|

|

|

|

| Mating male and female in San Bernardino County © Emily Mastrelli |

This is the same San Bernardino County mating female seen above after mating and after the male has left the scene. You can see semen and marks in the sand from the encounter.

© Emily Mastrelli |

Mating male and female in Riverside County © Emily Mastrelli |

| |

|

|

|

| Desert Tortoise Scat |

|

|

|

|

Tortoise scat © Arthur Davenport

|

Tortoise scat © Michelle Tollett |

A handful of tortoise scat © Jeff Ahrens |

Adult in burrow with scat, San Bernardino County © Jeff Ahrens |

|

|

|

|

A desert tortoise burrow with lots of scat and some egshell fragments

© Jeff Ahrens |

Desert Tortoise scat © Jeff Ahrens |

Desert Tortoise scat © Jeff Ahrens |

Burrow and scat, San Bernardino County © Jeff Ahrens |

| |

|

|

|

| Habitat and Burrows |

|

|

|

|

| Entrance to burrow, Kern County |

Entrance to burrow, Kern County |

Habitat in spring during a wet year,

San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, desert flats, Kern County |

Habitat, San Bernardino County |

Habitat, San Bernardino County |

Tortoise in habitat, Riverside County |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, San Bernardino County

© Jeff Ahrens |

Burrow, San Bernardino County

© Jeff Ahrens |

Habitat, San Bernardino County

© Jeff Ahrens |

Tortoise in the mouth of a burrow, San Bernardino County © Kate Britsch |

|

|

|

|

| Tortoise burrows © Michelle Tollett |

Habitat in Spring, Kern County

© Lou Silva |

| |

|

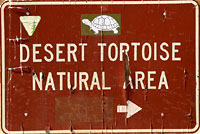

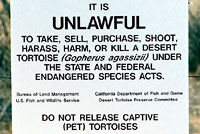

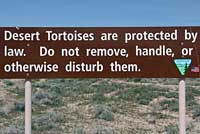

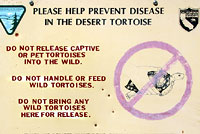

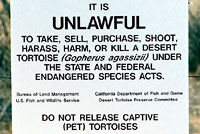

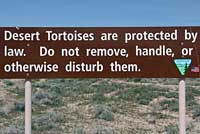

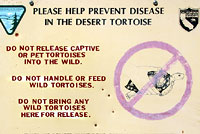

| Signs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

| A young Desert Tortoise walks along a rocky wash in the Mohave desert. |

Kicking dirt out behind it, an adult Desert Tortoise crawls back into its summer burrow. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

The Desert Tortoise has been the official reptile of the state of California since 1972.

|

| Size |

8 - 15 inches in shell length (20.3 - 38.1 cm). (Stebbins 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A large, slow-moving, terrestrial desert turtle with a high domed shell composed of large scutes marked with many growth lines, large elephantine rear feet, and stocky forelimbs covered with large conical scales.

The carapace is un-keeled, with a serrated rear rim.

A nuchal scute is present on the carapace (the scute directly behind the head). |

| Color and Pattern |

Color is tan, brown, grayish brown, to blackish and usually without any pattern.

The scutes may brownish or orange centers, particularly on young individuals.

Skin on the limbs and head is brownish, and the limb sockets and neck skin are yellowish. The plastron is unhinged and yellow or brownish in color. |

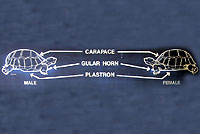

| Male / Female Differences |

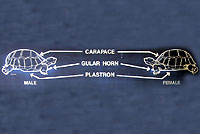

Males are larger than females with a concave plastron, a longer, thicker tail, and massive claws.

The

chin glands on each side of the lower jaw are larger on males.

The gular shields (throat shields - on the front of the shell below the head) are longer on males.

|

| Young |

Young have a flexible shell, long sharp nails, and a lighter carapace than adults.

Color is dull yellow to light brown with dark borders around the shields.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Terrestrial, spending most of its life in underground burrows.

This tortoise can live up to 50 years, possibly as long as 80 years.

The feeding and activity period of this species is very short, and mostly restricted to spring.

Most active during the day in spring, early summer, and during summer rains, becoming more active in early morning and late afternoon as seasonal temperatures increase. There may be another period of activity in the early fall as new sprouts germinate.

Winter hibernation begins from October to November, and often occurs in a communal den.

During the cold of winter, the heat of summer, or very dry years, a tortoise remains in a underground burrow which provides it with a more constant temperature and higher humidity. Tortoises dig the burrows in dry gravelly, or sandy soil often at the base of a bush. The burrows are she shape of a half circle, and typically measure 3 - 9 feet long, but have been measured at 30 feet long in the colder part of its range. Different burrows are constructed for different purposes. Spring burrows are shallow. During spring tortoises may simply rest under a shaded bush. Summer burrows are typically shorter and dug on flat ground, while wintering dens are longer and often dug at the top of a steep bank.

Desert tortoises are subject to dehydration due to loss of water through evaporation and urination. Tortoises will drink water when it is available during infrequent rains, but when water is not available, they rely on water stored in the bladder. When frightened, especially when picked up, a Desert Tortoise will often void the contents of its bladder, putting it at risk of dehydration.

Desert Tortoises exhibit some interesting social behaviors, including head bobbing when two tortoises meet, male combat and other territorial behavior, including vocal sounds and hissing.

A Desert Tortoise may live as long as 150 years. Adults become sexually mature at 15 - 20 years.

Native Americans used Desert Tortoises for food. A tortoise was placed on its back on a fire. When the shell cracked, the tortoise was ready to eat. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Herbivorous.

Eats plant material such as grass, cactus, herbs, flowers, and legumes. Non-native plants are rarely eaten. The most important plants in the diet are annual plants, which have a life span of only about a month, and are only available from April to June.

The annual feeding period may last only last from 6 - 12 weeks in a good year, and good years only occur on an average of one in five years. |

| Reproduction |

Courtship and breeding occur soon after emergence from hibernation in March and April. Males combat each other for access to females, using their enlarged gular horns to ram and possibly overturn another tortoise.

A tortoise that cannot right itself, is in danger of dying from overexposure to the sun.

Females lay a clutch of 1 - 12 eggs from May to July, usually at the opening of or just inside a burrow.

1 - 3 clutches might be laid in favorable years.

The eggs hatch from mid August to October.

|

| Habitat |

A desert species that needs firm ground in order to dig burrows, or rocks to shelter among.

In California it is found in arid sandy or gravelly locations along riverbanks, washes, sandy dunes, alluvial fans, canyon bottoms, desert oases, rocky hillsides, creosote flats and hillsides.

|

| Geographical Range |

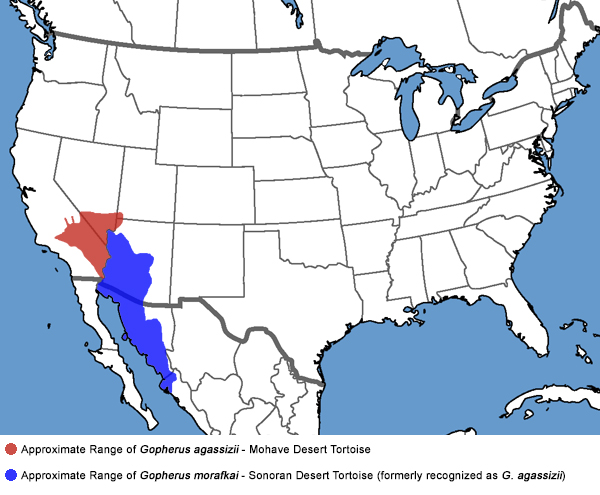

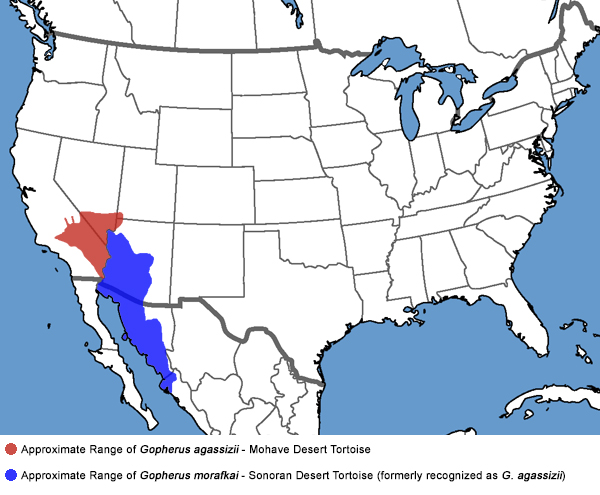

The species previously known as Gopherus agassizii was split into two species:

Gopherus agassizii - occurs only in California, extreme southern Nevada, extreme southwest Utah, and extreme northwest Arizona;

Gopherus morakfai - occurs from the Colorado River in extreme Southern Nevada south and east through much of western Arizona, and farther south along the Pacific Coast of Mexico to northern Sinaloa.

Range In California

The Mohave Desert Tortoise is found throughout the Mojave Desert and south along the Colorado river and along the east side of the Salton Basin in Sonoran Desert. Absent from the Coachella Valley.

Introduced Populations

There is an introduced population

of Desert Tortoises in Anza-Borrego State Park, San Diego County. (There is a picture of one above.) I have not yet found anything in print that explains their presence there. According to comments by Jeff Lemm in his field guide to reptiles and amphibians in San Diego County (2006) the Desert Tortoise "...is rarely seen in San Diego County. Specimens in San Diego County are believed to be introduced once-captive animals and their offspring (K. Berry, pers. comm.)"

On a March 2015 flickr page naturalist Donald Endicott, co-author of 50 Best Short Hikes San Diego, posts a picture of a tortoise he photographed at Anza-Borrego State Park and writes that pet tortoises were intentionally released into the area in 1970 and 1971 to repatriate them and to establish a reserve for the species in a suitable habitat, but he does not provide a source for the information.

Stebbins & McGinness (2012) comment that the Desert Tortoise "...is absent from the Coachella Valley except from the Boyd Deep Canyon Research Center area. The historical situation in this valley may be confusing because of escaped or released pet tortoises."

|

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

'The spelling of the word "Mojave" or "Mohave" has been a subject of debate. Lowe in the preface to his "Venomous Reptiles of Arizona" (1986) argued for "Mohave" as did Campbell and Lamar (2004, "The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere"). According to linguistics experts on Native American languages, either spelling is correct, but using either the "j" or "h" is based on whether the word is used in a Spanish or English context. Given that this is an English names list, we use the "h" spelling (P. Munro, Linguistics, UCLA, pers. comm.).'

(Taxon Notes to Crotalus scutulatus, SSAR Herpetological Circular no 39, published August 2012, John J. Moriarty, Editor.)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Robert W. Murphy, Kristin H. Berry, Taylor Edwards, Alan E. Leviton, Amy Lathrop, and J. Daren Riedle, in a June 2011 publication * found that the original publication date for the description of Xerobates agassizii, Agassiz Land-Tortoise, which was given as 1863, was actually 1861 and that the specimen was from California, not Arizona.

Citing significant differences in DNA and morphological, physiological, and ecological characteristics, they determined that Gopherus agasizii consists of two species, which they name Gopherus agassizii and Gopherus morafkai. G. morafkai represents the tortoises formerly classified as G. agassizii occurring east and south of the Colorado River in Arizona, and western Mexico. G. agasizii represents those tortoises occurring west and north of the Colorado River, in California, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona. They suggested the common names Agassiz's Desert Tortoise for G. agassizii, and Morafka's Desert Tortoise for G. morafkai, but the SSAR wisely decided to support the recognition of the traditional geographic standard names - Mohave Desert Tortoise, and Sonoran Desert Tortoise.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gopherus Rafinesque, 1832—North American Tortoises

"Standard English name changed from Gopher Tortoises to better reflect the content of Gopherus."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Gopherus agassizii - Desert Tortoise (Stebbins 1985, 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Gopherus agassizi - Desert Tortoise (Stebbins 1954, 1966)

Testudo agassizii - Desert Tortoise (Gopherus agassizii; Xerobates berlandieri. Agassiz's Gopher, Western Gopher, Agassiz's Tortoise, Agassiz's Land Tortoise) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

Listed for years as a threatened species by the state and federal governments, in April, 2024 the California Fish and Game Commission voted unanimously to list the Mohave Desert Tortoise as endangered under the California Endangered Species Act.

The Desert Tortoise population has declined significantly due to human activity in the desert. Military land development, urban development, off-road vehicle use, mining, overgrazing, agricultural development, intrusion of non-native plants, and Upper Respiratory Tract Disease have all been pointed out as probable causes for this decline. In addition, urban development of the desert leads to an increase in sources of food and water, including garbage, that are used by native ravens, allowing them to increase their numbers. The Desert Tortoise suffers with this population increase because ravens prey on young tortoises. Release of captive pet Desert Tortoises has also been considered detrimental.

The discovery that the desert tortoise actually consists of two unique species reduces the geographic range of G. agassizii to around 30 per cent of its former range which heightens the need for the conservation of the species.

According to the group Defenders of Wildlife, the tortoise population in the western Mojave Desert has declined by 90 percent since the early 1980s. Military bases in the area with healthy tortoise populations

have been charged with protecting the tortoises by monitoring their health and conducting training exercises away from tortoise-heavy areas. Large-scale tortoise relocation efforts have also been attempted, and more have been planned, but after it was learned that more than 30 percent of tortoises relocated died in a 2008 relocation project at Fort Irwin, the effectiveness of relocation has been debated. A study conducted by Federal officials blamed a drought for the tortoise deaths, claiming that 30 percent of non-relocated tortoises also died in the drought, but Environmental groups disputed the finding. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist Brian Croft, who has dealt with the problems of relocating tortoises, says that as long as translocation is planned properly, it can be successful. (Washington Post 6/28/16)

|

| Official California State Reptile |

The legislation was proposed by students at the Benjamin Bubb School in Mountain View and sponsored by Assemblyman Richard D. Hayden of Sunnyvale.

It was made law in 1972. Being an official state reptile still doesn't protect you from bulldozers, so I'm not sure what good it is. |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Testudinidae |

Land Tortoises |

Gray, 1825 |

| Genus |

Gopherus |

Gopher Tortoises

(North American Tortoises) |

Rafinesque, 1832 |

Species

|

agassizii |

Mohave Desert Tortoise |

(Cooper, 1863) |

|

Original Description |

Gopherus agassizii - (Cooper, 1863) - Proc. California Acad. Sci., Vol. 2, p. 120

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Gopherus - French - gaufre = small burrowing animal - probably referring to its burrowing habits.

agassizii - honors Agassiz, Jean Louis R.

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

According to James R. Buskirk, the meaning of the word "gaufre" in French is honeycomb, not a small burrowing animal. "The word may thus refer to the anastomosing tunnels of these fossorial chelonians," or an "alternative explanation for the origin of Gopherus is that it is derived from a West African word for chelonian, mungofa."

|

|

Related or Similar California Turtles |

A. m. pallida - Southern Pacific Pond Turtle

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Desert Tortoise Preserve Committee

Center for Biological Diversity

* Murphy RW, Berry KH, Edwards T, Leviton AE, Lathrop A, Riedle JD (2011) The dazed and confused identity of Agassiz’s land tortoise, Gopherus agassizii (Testudines, Testudinidae) with the description of a new species, and its consequences for conservation. ZooKeys 113: 39–71. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.113.1353

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Carr, Archie. Handbook of Turtles: The Turtles of the United States, Canada, and Baja California. Cornell University Press, 1969.

Ernst, Carl H., Roger W. Barbour, & Jeffrey E. Lovich. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Smithsonian Institution 1994.

(2nd Edition published 2009)

Lemm, Jeffrey. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of the San Diego Region (California Natural History Guides). University of California Press, 2006.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G3 |

Vulnerable |

| NatureServe State Ranking |

S2S3 |

Imperiled - Vulnerable |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

FT |

Listed as Threatened 4/02/1990 |

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

ST

Endangered |

Listed as Threatened 8/03/1989

Candidate for Endangered Species 10/19/2020.

In April, 2024 the California Fish and Game Commission voted unanimously to list the Mohave Desert Tortoise as endangered.

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

VU |

Vulnerable |

|

SCE 2020/10/19

|

|