|

|

| Adult male, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

| |

Adult male, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult male, San Bernardino County |

Closed eye showing fringed eyelids |

Adult male, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

| Adult male, San Bernardino County |

Adult, San Bernardino County

© Brad Alexander |

Adult, San Bernardino County

© Jeremiah Easter |

|

|

|

Adult, San Bernardino County

© Zachary Cava |

Pale adult female, San Bernardino County sand dunes

© Zeev Nitzan Ginsburg |

Adult, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

| Adult, San Bernardino County |

Adult, San Bernardino County |

Adult buried in the sand, Riverside County © Zachary Cava |

|

|

| Adult, Riverside County © Zachary Cava |

|

|

|

| Black blotches on the back do not merge - there are no broken lengthwise lines |

Dark lines on the lower throat form crescent-shaped markings |

Underside has a black mark

on the lower sides |

|

|

|

Fringes on toes of rear foot.

These fringes give the lizard genus its common name. They give the toes more surface area to keep them from sinking as the lizard moves over fine wind-blown sand. |

Footprints left by the lizard shown above in the top row as it quickly ran away.

|

The Fringe-toed Lizards, genus Uma, have soft and smooth skin with granular scales.

|

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

Habitat, low, wind-blown sandy wash, San Bernardino County

|

Habitat, low dunes,

San Bernardino County |

Distant view of wind-blown sand dunes habitat, San Bernardino County |

|

|

|

Habitat, massive sand dunes,

San Bernardino County

|

Close-up of part of the dunes shown to the left, San Bernardino County

|

Habitat, massive sand dunes,

San Bernardino County

|

|

|

|

Habitat, San Bernardino County

|

Sign, San Bernardino County |

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

Watch a lizard bury itself in the sand to hide. This lizard was captive and sluggish and buries itself slowly and incompletely. In the wild a fringe-toed lizard will run quickly then disappear in a flash as it dives into the sand.

|

Watch this llizard run quickly over the sand to escape. It almost escaped the camera... |

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

2 3/4 to 4 1/5 inches long from snout to vent (7 - 11.4 cm). (Stebbins 2003)

The tail is about the same length as the body.

|

| Appearance |

A medium-sized, flat-bodied, smooth-skinned lizard that inhabits areas of loose sand.

|

| Color and Pattern |

Color is white or grayish, with a contrasting pattern of black blotches and eye-like spots.

Black blotches on back do not form broken lengthwise lines, unlike on other species of fringe-toed lizards in California.

The color and pattern create a successful camouflage which allows a lizard to blend into its sandy habitat.

The underside is pale with black bars on the underside of the tail and a black mark on the lower sides.

Dark crescent-shaped lines on the throat differentiate this from other species of fringe-toed lizards in California. |

| Male / Female Differences |

Males have two enlarged post-anal scales, distinct femoral pores, a hemipenal bulge at the base of the tail, and a greenish wash on the belly with pink on the sides of the body during the breeding season.

Females have a more pronounced pink coloring on the sides during the breeding season.

|

| Comparison With Similar Species |

Comparison of the three species of Fringe-toed Lizards found in California.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Diurnal.

Adapted to living in areas with fine windblown sand.

Goes underground in the sand or in a burrow in November, and emerges in February.

Young lizards may go under later and emerge earlier.

Takes cover in the sand to avoid extreme temperatures.

Commonly sleeps in the sand under a bush at night.

A fringe of scales on the sides of the toes help this lizard run quickly over fine sand, preventing them from sinking, similar to the effect of wearing snowshoes.

Scales are granular and very small, which helps a lizard bury itself quickly in fine sand.

A countersunk lower jaw, eyelids that overlap, flaps over the ears, and nostrils and nasal passages which work like valves, all prevent sand from getting into a lizard's orifices and lungs.

The parietal eye, an eye-like structure on top of the head, is thought to help this lizard monitor the amount of solar radiation it receives to help it avoid too much or too little heat.

On waking in the morning, a lizard often basks with just the head above the sand until its body temperature warms sufficiently to allow it to unbury the entire body and continue basking or begin activity. |

| Defense |

| When scared, this lizard will run very quickly on its hind legs to the opposite side of a bush or a small sand hill, and run into a burrow or dive into the sand. Sometimes they will stop and freeze underneath a bush. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats primarily small invertebrates such as ants, beetles, and grasshoppers, along with occasional blossoms, leaves, and seeds. The consumption of plant material may inadvertently occur when a lizard is eating insects.

Adults will also eat lizard hatchlings. |

| Reproduction |

Lays 1 - 5 eggs from May to July.

|

| Habitat |

Sparsely-vegetated arid areas with fine wind-blown sand, including dunes, flats with sandy hummocks formed around the bases of vegetation, washes, and the banks of rivers. Needs fine, loose sand for burrowing.

|

| Geographical Range |

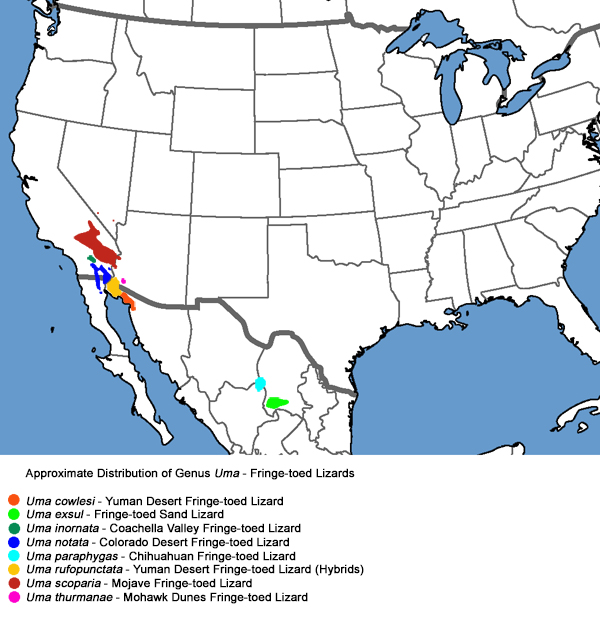

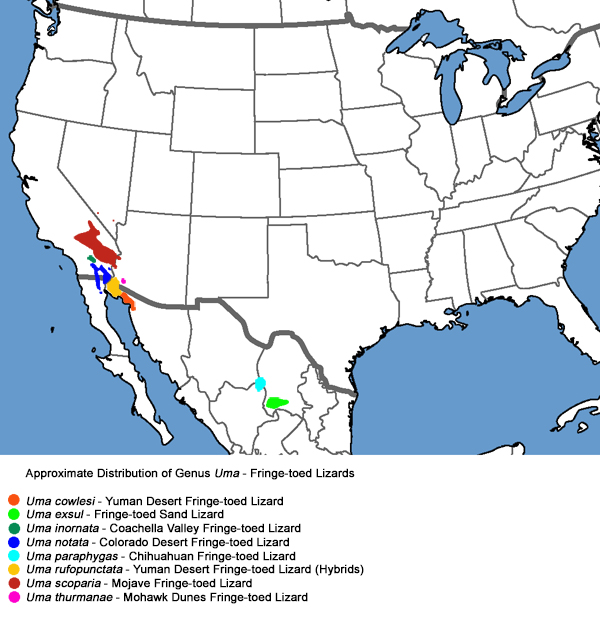

Inhabits areas of fine windblown sand in the Mohave Desert from the southern end of Death Valley south to the Colorado River around Blythe, and into extreme western Arizona.

In 2016 a juvenile fringe-toed lizard was collected at the Amargosa Sand Dunes in Nye County, Nevada, about 70 miles north of their former northernmost documented locations at the Ibex and Dumont Dunes in California.

In 2019 fringe-toed lizards were vouchered from the Apex Dunes northeast of Las Vegas, 154 kilometers northeast of the nearest known records at east Soda Dry Lake

in the Mojave National Preserve.

(Herp Review, June 2022)

Fringe-toed Lizards, genus Uma, can be found in Arizona, California, Nevada, and in Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuilla, and Durango, Mexico.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

From about 300 ft. to 3,000 ft. (90 - 910 m). (Stebbins 2003)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

'The spelling of the word "Mojave" or "Mohave" has been a subject of debate. Lowe in the preface to his "Venomous Reptiles of Arizona" (1986) argued for "Mohave" as did Campbell and Lamar (2004, "The Venomous Reptiles of the Western Hemisphere"). According to linguistics experts on Native American languages, either spelling is correct, but using either the "j" or "h" is based on whether the word is used in a Spanish or English context. Given that this is an English names list, we use the "h" spelling (P. Munro, Linguistics, UCLA, pers. comm.).'

(Taxon Notes to Crotalus scutulatus, SSAR Herpetological Circular no 39, published August 2012, John J. Moriarty, Editor.)

Tre´panier and Murphy (2001) determined that 5 species of Uma inhabit the U.S.:

Uma scoparia,

Uma inornata,

Uma notata,

Uma rufopunctata,

and an unnamed species from the Mohawk Dunes in Arizona.

In 2020 Uma rufopunctata was shown to represent a hybrid population between Uma notata and Uma cowlesi.

The population in the Mohawk Dunes in Arizona was re-named the Mohawk Dunes Fringe-toed Lizard - Uma thurmanae.

[Derycke, Gottscho, Mulcahy, & De Queiroz "A new cryptic species of fringe-toed lizards from southwestern Arizona with a revised taxonomy of the Uma notata cpecies complex (Squamata: Phrynosomatidae) Zootaxa 4778 (1) 67-100]

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Uma scoparia - Mojave Fringe-toed Lizard (Stebbins 1966, 1985, 2003)

Uma scoparia - Mojave Sand Lizard (Stebbins 1955)

Uma scoparia - Crescent Uma (Smith 1946)

Uma notata - Ocellated Sand Lizard (Uma inornata; Ocellated Desert Lizard; Red-spotted Desert Lizard; Cope's Desert Lizard; Spotted Yuma Lizard.) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

Highly vulnerable to off-road vehicle activity and the establishment of windbreaks that affect how windblown sand is deposited. (Stebbins 2003)

Protected from take with a sport fishing license in 2013.

Mohave Fringe-toed Lizards at the Ibex Dunes and the Dumont Dunes in extreme northern San Bernardino County in the Amargosa River drainage are a distinct population which is isloated from those to the south. An endangered species petition to protect them from off-road vehicle activity at the dunes was submitted in 2006. |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Phrynosomatidae |

Zebra-tailed, Earless, Fringe-toed, Spiny, Tree, Side-blotched, and Horned Lizards |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Genus |

Uma |

Fringe-toed Lizards |

Baird, 1859 “1858” |

Species

|

scoparia |

Mohave Fringe-toed Lizard |

Cope, 1894 |

|

Original Description |

Uma scoparia - Cope, 1894 - Amer. Nat., Vol. 28, p. 435

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Uma - Yuma Native American group - possibly referring to its location in Arizona

scoparia - Latin - scopa = twigs + -aria = having

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Lizards |

U. inornata - Coachella Fringe-toed Lizard

U. notata - Colorado Desert Fringe-toed Lizard

C. d. rhodostictus - Western Zebra-tailed Lizard

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Jones, Lawrence, Rob Lovich, editors. Lizards of the American Southwest: A Photographic Field Guide. Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2009.

Smith, Hobart M. Handbook of Lizards, Lizards of the United States and of Canada. Cornell University Press, 1946.

The Coachella Valley Fringe-Toed Lizard (Uma inornata): Genetic Diversity and Phylogenetic Relationships of an Endangered Species Tanya L. Tre´panier and Robert W. Murphy

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution Vol. 18, No. 3, March, pp. 327–334, 2001

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G3G4 |

Vulnerable - Apparently Secure |

| NatureServe State Ranking |

S3S4 |

Vulnerable - Apparently Secure |

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

SSC |

Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management |

S |

Sensitive |

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

LC |

Least Concern |

|

|