|

|

| Adult with partly regenerated tail, Tulare County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult with mostly original tail, 6,200 ft., Tuolumne County |

|

Underside of adult, Tuolumne County

(Dark lines are between

the rows of scales) |

|

|

|

|

| |

Adult with partly regenerated tail, 5,600 ft. Tuolumne County |

Underside of adult, Tuolumne County

(Dark lines are between

the rows of scales) |

|

|

|

|

Adult, 6,200 ft., Tuolumne County

|

Adult with partly regenerated tail, Tuolumne County |

Adult, Tulare County

|

Underside of adult, Tulare County

(Dark lines are between

the rows of scales) |

|

|

|

|

| Adult with partly regenerated tail, 5,600 ft. Tuolumne County |

The powerful jaws of this lizard allow it to bite hard and hold on.

Human skin is rarely broken, just pinched hard. |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Kern County

© Noah Morales |

Adult, Kern County

© Noah Morales

|

Adult, Mono County © Keith Condon |

|

|

|

|

Adult female, Inyo County

© Adam Clause |

Adult male, Inyo County

© Adam Clause |

Sub-adult male, Inyo County

© Adam Clause |

Adult with regenerated tail and juvenile, with broken tail, Plumas County |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Kern County

© Ryan Sikola |

This very dark sub-adult was found at about 8,100 ft. elevation in the

Sierra Nevada mountains in El Dorado County. © Jorah Wyer |

Adult with original tail , Butte County

© Jackson Shedd, specimen courtesy of John Stephenson

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult with original tail, Plumas County - possible intergrade with E. c. shastensis. |

Adult, Butte County, probable intergrade with E. c. shastensis.

© Mela Garcia |

|

|

|

|

| An adult male with his hemipenis everted. |

It is common to find blood-engorged ticks attached to alligator lizards, especially in and around the ear openings, as you can see on the

Shasta Alligator Lizard on the left and on the

San Francisco Alligator Lizard on the right.

|

|

|

|

|

Western Alligator Lizards, genus Elgaria, have large rectangular keeled scales on the back that are reinforced with bone.

(Elgaria multicarinata multicarinata is shown here). |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Juveniles |

|

|

|

|

| Juvenile with broken tail, Plumas County |

Juvenile, Nevada County

© Robin Chanin |

Adult and juvenile, Plumas County |

| |

|

|

| Northern Alligator Lizard Breeding Behavior |

|

|

|

|

These two mating adults were spotted on a forest trail on an afternoon in late June in Plumas County.

© 2005 Todd Accornero

|

An adult male Alligator Lizard from the intergrade zone in northern Sonoma County

courts a female by biting onto her neck in late May. © Laura Baker |

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

Habitat, small creek in forest,

7,200 ft., Tulare County |

Habitat, 7,200 ft., Tulare County

|

Habitat, 4,100 ft., Plumas County |

Habitat, Inyo County

© Adam Clause |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, 6,200 ft., Tuolumne County |

Habitat, 6,200 ft., Tuolumne County |

Habitat, 5,600 ft., Tuolumne County |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

|

| A Sierra Alligator Lizard bites and holds onto my finger, then releases its jaws and crawls into a rock crack. |

This video shows how an alligator lizard's tail thrashes around after it has been dropped to distract a predator. The tail moved for about 4-5 minutes, which has been cut down here to about a minute, showing several different speeds until it is just barely moving. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Elgaria coerulea ranges from 2 3/4 - 5 7/8 inches in snout to vent length (7 - 13.6 cm) (Stebbins)

|

| Appearance |

Alligator lizards, genus Elgaria, are members of the family Anguidae, a family of lizards found in the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

They are characterized by a thick rounded body with short limbs and long tail.

Large bony scales, a large head on an elongated body and powerful jaws probably give the lizards their common name.

The tail can reach twice the length of its body if it has never been broken off and regenerated.

Scales are keeled on the back, sides, and legs, with 16 rows of scales across the back at the middle of the body.

(Compare with the 14 rows of scales found on the Southern Alligator Lizard - Elgaria multicarinata.)

The temporals are weakly keeled.

A band of small granular scales separates the larger bone-reinforced scales on the back and on the belly, creating a fold along each side. These folds allow the body to expand to hold food, eggs, or live young. The fold contracts when the extra capacity is not needed.

The head of a male is broader than a female's with a more triangular shape. |

| Color and Pattern |

Color is olive-brown, bluish, or greenish above, with dark mottling but usually no definite cross-bands.

The underside is yellowish or greenish.

Eyes

The eyes are relatively dark around the pupils compared with the light eyes of a similar species - the Southern Alligator Lizard - Elgaria multicarinata.

Lines on the Belly

Usually there are dark lines running lengthwise on the belly which run between the scales, along the edge of the scales.

(Compare with the underside lines on the Southern Alligator Lizard - Elgaria multicarinata which run through the middle of the scales.)

|

Identifying Alligator Lizards in California |

| Young |

Newborn lizards are very thin and small, roughly 4 inches long, with smooth shiny skin with a plain tan, light brown, or copper colored back and tail. The sides are darker and sometimes mottled or barred as they are on adults. Juveniles gradually develop the large scales and heavy dark barring found on the back and tails of adults.

|

| Life History and Behavior |

Activity |

Active during the day.

Inactive during cold periods in winter.

This subspecies has a shorter activity period than the others due to its higher-elevation habitat.

Moves with a snake-like undulating motion.

A good swimmer, sometimes diving into the water to escape by swimming away.

Alligator lizards are generally secretive, tending to hide in brush or under rocks, although they are often seen foraging out in the open or on roads in the morning and evening. |

| Defense |

The tail of an alligator lizard is easily broken off, as it is with many lizards.

The tail will grow back, although generally not as perfectly as the original.

A lizard may detach its tail deliberately as a defensive tactic. When first detached, the tail will writhe around for several minutes, long enough to distract a hungry predator away from the lizard.

More information about tail loss and regeneration.

Males sometimes also extrude the hemipenes when threatened.

Often when an alligator lizard is observed lying still or basking, it will tuck its legs back toward the body. This is probably a defensive measure to break up the outline of the lizard's body so that a predator can't tell that it's an animal with legs. This might be to give it the appearance of a stick or shadow or something not alive, or it might be to imitate a snake, since many animals are naturally afraid of snakes and will hesitate to approach or attack a snake.

Other defensive tactics used by alligator lizards are smearing the contents of the cloaca on the enemy and biting.

They often bite onto a predatory snake, on the neck or the head, rendering the snake unable to attack.

Samuel M. McGinnis (Stebbins & McGinnis, 2012)

reports seeing a juvenile southern alligator lizard bite onto its own tail making itself impossible to be swallowed by a juvenile Alameda Striped Racer, which eventually gave up. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats a variety of small invertebrates, including slugs, snails, and worms. Will also eat small lizards and small mammals.

Occasionally feed on bird eggs and young birds. (Stebbins) |

| Reproduction |

After mating, the female carries her young inside her until they are born live and fully-formed sometime between June and September.

During the spring/summer breeding season, a male lizard grabs on to the head of a female with his mouth until she is ready to let him mate with her. They can remain attached this way for many hours, almost oblivious to their surroundings. Besides keeping her from running off to mate with another male, this probably shows her how strong and suitable a mate he is.

|

| Habitat |

Woodland, forests, grassland. Commonly found hiding under rocks, logs, bark, boards, trash, or other surface cover. Prefers wetter and cooler habitats than E. multicarinata, but generally found near sunny clearings.

|

| Geographical Range |

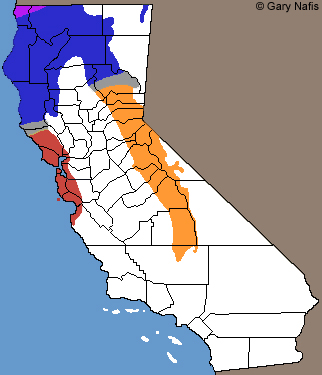

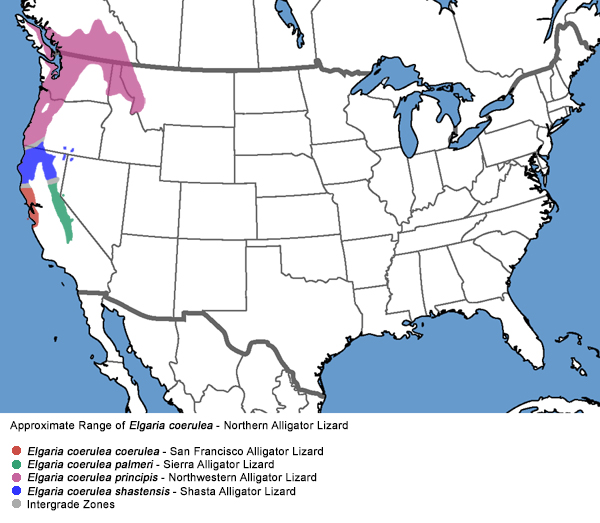

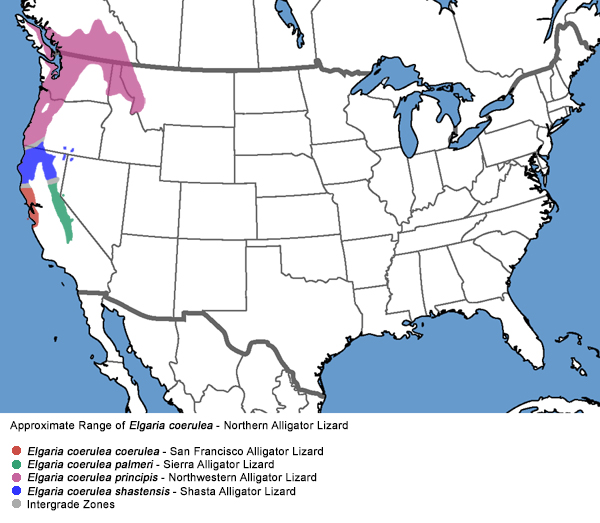

The subspecies Elgaria coerulea palmeri is found in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, from Plumas County south to Kern County where it occurs as far south as the Piute Mountains and Breckenridge Mountain.

The species Elgaria coerulea ranges from Southern British Columbia south chiefly west of the Cascades and Coast Ranges to northern Monterey County, east into northern Idaho and northwestern Montana, with isolated populations occurring in southeastern Oregon, northwestern Nevada and the Warner Mountains in California, and south through the Sierra Nevada Mountains to Kern County.

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Stebbins (2003) shows the elevational range of the species Elgaria coerulea as sea level to around 10,500 ft. (3,200 m.) but only the subspecies E. c. palmeri can be found that high up. The other subspecies range much lower.

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

In 2025 the SSAR recognized only 3 subspecies of Elgaria coerulea, with E. c. principis merged into E. c. coerulea.

E. c. coerulea (synonym: E. c. principis) - Northwestern Alligator Lizard

E. c. palmeri - Southern Sierra Alligator Lizard

E. c. shastensis - Northern Sierra Alligator Lizard

"Based on mtDNA, Lavin et al. (2018, Zoologica Scripta 47: 462–476) inferred 10 non-overlapping mitochondrial clades and six population clusters within E. coerulea and based on nuclear SNPs. Leaché et al. (2024, Journal of Heredity 115: 57–71) inferred 10 population clusters and nine multi-cluster clades that are only roughly consistent with subspecies proposed by Fitch (1938, American Midland Naturalist 20: 381–424). Neither set of authors proposed taxonomic changes, although Leaché et al. (op. cit.) performed analyses that failed to support more than one species within E. coerulea.

We have re-circumscribed the subspecies to correspond to the three major clades within E. coerulea inferred by Leaché et al. (op. cit.)

E. c. coerulea (synonym: E. c. principis) is applied to the clade of Pacific Northwest, Northern California, and Northern and Southern Coast Range clusters;

E. c. palmeri is applied to the clade of Southern and two Central Sierra Nevada clusters; and

E. c. shastensis is applied to the clade of Lower Cascades and two Northern Sierra Nevada clusters.

The standard English names have been changed to reflect the geographic distributions of the taxa."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

"The standard English name has been changed from “Sierra Alligator Lizard” to better reflect the distribution of this taxon."

(Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In a study published in April, 2018 * Brian R. Lavin et al reported the results of sequencing mtDNA of Elgaria coerulea:

"Our phylogeographic examination of E. coerulea uncovered surprising diversity and structure, recovering 10 major lineages, each with substantial geographic substructure."

They did not recommend any taxonomic changes, but they did name the lineages and illustrate their distribution:

1. Pacific Northwest

2. Interior Coast Range

3. North Coast Ranges

4. South Coast Ranges

5. Northern California

6. Yolla Bolly Mountains

7. Lower Cascades

8. Central Sierra Nevada

9. Northern Sierra Nevada

10. Southern Sierra Nevada

"The taxon appears to have a Sierra Nevada origin and then moved both north and west to occupy its current distribution (as postulated 60 years ago), diversifying into a number of geographically confined clades along the way. The patterns of range limits and clade boundaries shared between E. coerulea and other codistributed forest and woodland species provides compelling evidence that a handful of major biogeographic barriers and historical events (e.g., San Francisco Bay and Monterey Bay outlets, Sierra Nevada glaciation) have been instrumental in shaping phylogeographic patterns and have likely influenced species range limits and even patterns of community assembly in the California Floristic Province."

* Brian R. Lavin, Guinivere O.U. Wogan, Jimmy A. McGuire, and Chris R. Feldman.

Phylogeography of the Northern Alligator Lizard (Squamata, Anguidae): Hidden diversity in a western endemic.

© 2018 Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Zoologica Scripta. 2018; 1–15.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Elgaria coerulea palmeri - Southern Sierra Alligator Lizard (Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List)

Elgaria coerulea palmeri - Sierra Alligator Lizard (Stebbins 2003, 2012, 2018)

Gerrhonotus coeruleus palmeri - Sierra Alligator Lizard (Smith 1946, Stebbins 1954, 1966, 1985)

Gerrhonotus palmeri - Sierran Alligator Lizard (Gerrhonotus scincicauda palmeri; Gerrhonotus multicarinatus palmerii. Mountain Alligator Lizard) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

| None |

|

|

Taxonomy |

| Family |

Anguidae |

Alligator Lizards & Allies |

Gray, 1825 |

| Genus |

Elgaria |

Western Alligator Lizards |

Gray, 1838 |

| Species |

coerulea |

Northern Alligator Lizard |

Wiegmann, 1828 |

Subspecies

|

palmeri |

Sierra Alligator Lizard |

(Stejneger, 1893)

|

|

Original Description |

Elgaria coerulea - (Wiegmann, 1828) - Isis von Oken, Vol. 21, p. 380

Elgaria coerulea palmeri - (Stejneger, 1893) - N. Amer. Fauna, No. 7, p. 196

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Elgaria - obscure - possibly named for an "Elgar" or a pun on "alligator."

coerulea - Latin = dark colored, dark blue - referring to the dorsal color of the type specimen

palmeri - honors Palmer, Theodore S.

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Lizards |

E. c. coerulea - San Francisco Alligator Lizard

E. c. shastensis - Shasta Alligator Lizard

E. c. principis - Northwestern Alligator Lizard

E. multicarinata - Southern Alligator Lizard

E. panamintina - Panamint Alligator Lizard

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Jones, Lawrence, Rob Lovich, editors. Lizards of the American Southwest: A Photographic Field Guide. Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2009.

Smith, Hobart M. Handbook of Lizards, Lizards of the United States and of Canada. Cornell University Press, 1946.

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

This animal is not included on the Special Animals List, which indicates that there are no significant conservation concerns for it in California.

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

|

|

| NatureServe State Ranking |

|

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

None |

|

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

|

|

|

|