|

|

| Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Purple and red underside of adult, Bakersfield, Kern County

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

|

Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County

© Ryan Sikola |

Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County

© Ryan Sikola |

|

|

|

|

| Legless lizard found under a board sitting on sandy soil and burrow channels under the board, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

| Adult, from the isolated population in extreme eastern San Luis Obispo County. Note how the black tail tip seems to mimic the black head. © Ryan Sikola |

Head |

Tail |

|

|

|

|

Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County © William Flaxington

|

Adult, Bakersfield, Kern County |

North American Legless Lizards, genus Anniella, have smooth cycloid scales. |

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

|

| Habitat, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Habitat, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Habitat, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Habitat of type locality, sand ridge near Bakersfield, Kern County |

|

|

|

|

| Microhabitat, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Habitat, Bakersfield, Kern County |

Habitat, Bakersfield, Kern County |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Predation on Legless Lizards |

|

|

|

|

| Ring-necked Snakes use a mild venom to subdue their prey which include snakes and lizards. This snake from San Diego County regurgitated a legless lizard that it had recently eaten. © Donald Schultz |

| |

| Short Videos of this and other Anniella Species |

|

|

|

|

| A Bakersfield Legless Lizard crawls and burrows into loose soil in Bakersfield. |

A Bakersfield Legless Lizard crawls and burrows into loose soil in Bakersfield. |

A Bakersfield Legless Lizard in Bakersfield. |

|

|

|

|

|

| A San Diegan Legless Lizard crawls then quickly burrows into loose soil in Riverside County. |

A San Diegan Legless Lizard writhes around rapidly on a board in Riverside County. Accustomed to living on soft sand it can burrow into, it has difficulty moving on the hard surface. |

Black Legless lizards burrow into Monterey County sand dunes. |

The detached tail of a San Diegan Legless Lizard wriggles rapidly, looking like a living creature, until it gradually slows down. This illustrates how a lizard can drop its tail to distract a predator then crawl away to safety while the predator chases the tail.

(This tail was not removed intentionally, it was unexpectedly dropped by the lizard when it was stressed from being handled.) |

| |

|

|

|

| Description |

|

| Size |

Size range not Known. The following size information is based on descriptions of Anniella pulchra before it was split into five species.

4 - 3/8 to 7 inches long from snout to vent (11.1 - 17.8 cm). (Stebbins, 2003)

|

| Appearance |

A small slender lizard with no legs, eyelids, a shovel-shaped snout, smooth shiny scales, and a blunt tail.

Sometimes confused for a snake, but snakes have no eyelids. On close observation the presence of eyelids is apparent when this lizard blinks.

|

| Color and Pattern - from Papenfuss and Parham (2013) |

Dorsum is light olive-grey.

The sides are strong orange.

Ventral color is grayish red (appears purple.)

A mid-dorsal black stripe 1/2 scale wide is present from the parietals to the tip of the tail.

Lateral black stripes one scale wide are present from the eye to the tip of the tail.

|

| Comparison With Other Species of Anniella |

"Distinguished from all other species of Anniella by a unique ventral coloration of Grayish Red. ... This coloration is continuous from the anterior end of the lower jaw to the end of the tail."

A. grinnelli has a higher vertebral count than A. pulchra, A. stebbinsi, and A. campi.

See Comparison Chart

|

Life History and Behavior

|

Little information is available about the life history and behavior of A. grinnelli.

The following information is based on descriptions of Anniella pulchra before it was split into five species, unless otherwise indicated.

|

| Activity |

Does not bask in direct sunlight.

Tolerance of low temperatures allows activity in cool conditions.

Lives mostly underground, burrowing in loose sandy soil.

Forages in loose soil, sand, and leaf litter during the day.

Sometimes found on the surface at dusk and at night.

Apparently active mostly during the morning and evening when they forage beneath the surface of loose soil or leaf litter which has been warmed by the sun.

Specimens of A. campi have been found in April and May.

|

| Defense |

The tail can become detached and writhe on the ground for several minutes to distract a potential predator while the lizard escapes.

More information about tail loss and regeneration. |

| Predators |

| Known predators include ringneck snakes, common kingsnakes, deer mice, long-tailed weasels, domestic cats, California thrashers, American robins, and loggerhead shrikes. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats primarily larval insects, beetles, termites, and spiders.

Conceals itself beneath leaf litter or substrate then ambushes its prey. |

| Reproduction |

Bears live young.

Probably breeds between early spring and July, with 1 - 4 young (usually 2) born between September and November.

|

| Habitat (Based on descriptions of Anniella pulchra before it was split into five species.) |

Occurs in moist warm loose soil with plant cover. Moisture is essential. Occurs in sparsely vegetated areas of beach dunes, chaparral, pine-oak woodlands, desert scrub, sandy washes, and stream terraces with sycamores, cottonwoods, or oaks. Leaf litter under trees and bushes in sunny areas and dunes stabilized with bush lupine and mock heather often indicate suitable habitat. Often can be found under surface objects such as rocks, boards, driftwood, and logs. Can also be found by gently raking leaf litter under bushes and trees. Sometimes found in suburban gardens in Southern California.

|

| Geographical Range |

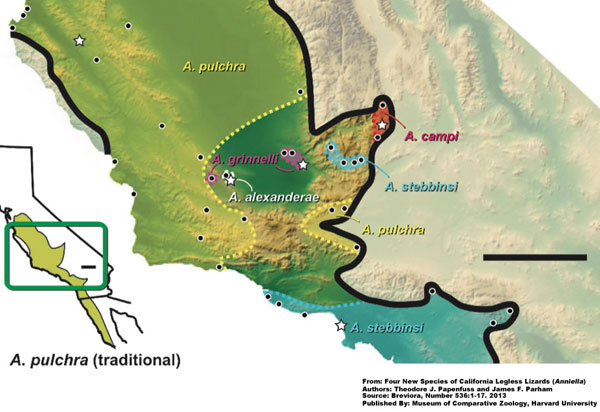

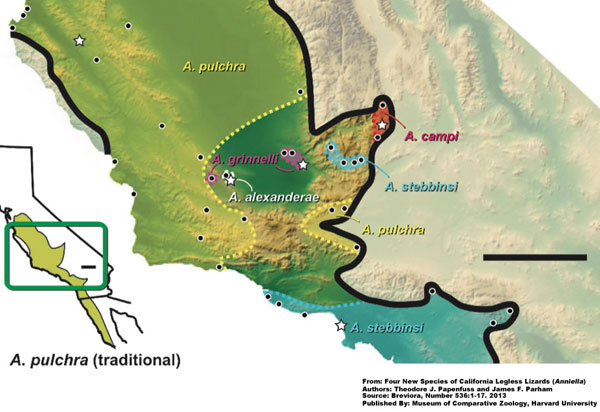

Restricted to the southern San Joaquin Valley and the east side of the Carrizo Plain, including within the city limits of Bakersfield.

"During the last 10 years, two of the three known Bakersfield populations were destroyed by housing development. A protected population is located at the type locality, the Sand Ridge Preserve. Individuals from the Carrizo Plain are similar in coloration and mitochondrial sequences to San Joaquin samples but have a nuclear genotype known only from lineage B. Parham and Papenfuss (2009) speculated that this population may be a hybrid or intergrade population, but we include Carrizo specimens in our concept of A. grinnelli."

Papenfuss and Parham (2013)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

In 2008 Parham and Pappenfuss (2008)2 using mt and nuDNA found five previously unrecognized genetic lineages of Anniella pulchra that are evolving independently.

In September of 2013 by Papenfuss and Parham3 divided the existing one species of legless lizard into five species based on the five lineages from their 2008 study2, naming four new species and giving a new common name to the species now known as Anniella pulchra. The five species are:

Anniella alexanderae - Temblor Legless Lizard

Anniella campi - Southern Sierra Legless Lizard

Anniella grinnelli - Bakersfield Legless Lizard

Anniella pulchra - Northern California Legless lizard

Anniella stebbinsi - Southern California Legless Lizard

Range Map of 5 Species:

Subspecies

Anniella pulchra is traditionally split into two subspecies - Anniella pulchra pulchra - Silvery Legless Lizard, and Anniella pulchra nigra - Black Legless lizard, but these subspecies are no longer recognized by the SSAR (whose taxonomy is followed here) because of a 2000 study that showed that A. p. nigra and the Morro Bay populations have been found to have different evolutionary ancestors than A. p. pulchra, but not enough to warrant recognition as a distinct taxon. The 2008 study by Parham and Pappenfuss does not provide any information regarding these subspecies, but it does separate A. p. nigra into its own group, and the authors, in personal communications with an environmental scientist with the California Department of Fish and Game (related to me October 2010) have said that there is information that supports the recognition of A. p. nigra as a separate subspecies or even as a unique species, and their belief is that Pearse and Pogson did not mean to completely sink the subspecies, they meant to show that it had diverged significantly from the Morro Bay population, which should not be considered A. p. nigra.

From the SSAR Official Names List 6th Edition, 2008:

"Pearse and Pogson (2000, Evolution 54: 1041–1046) presented evidence that the melanistic form previously designated Anniella pulchra nigra is polyphyletic, its Monterey Bay and Morro Bay populations having been derived independently from the silvery form previously designated A. p. pulchra. Although Pearse and Pogson did not propose any taxonomic changes, their results indicate that the subspecies A. p. pulchra and A. p. nigra do not correspond with separated or partially separated lineages, and therefore we do not recognize subspecies within A. pulchra. The existence and extent of genetic continuity between populations of melanistic and silvery legless lizards, as well as between northern and southern mtDNA haplotype clades, deserves further study."

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Anniella pulchra pulchra - Silvery Legless Lizard (Stebbins 2003)

Anniella pulchra pulchra - California Legless Lizard

- (Stebbins 1954, 1985)

Anniella pulchra pulchra - Silvery Footless Lizard - (Smith 1946)

Shovel-snouted Legless Lizard

Anniella pulchra pulchra - Silvery Footless Lizard (Anniella texana. Blue Worm-snake, part; Blind Worm; Worm Snake, part; Worm Lizard) (Grinnell and Camp 1917)

|

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

See Conservation Status note below.

All Anniella were protected from take with a sport fishing license in 2013.

Much of this lizard's habitat has been lost due to agriculture, housing development, sandmining, and other human land development, recreation, especially off-road vehicles in coastal dune areas, and by the introduction of exotic plants such as ice plant.

"The former A. pulchra, a species of special concern (Jennings and Hayes, 1994), is now divided into five species. This means A. pulchra has a smaller distribution than previously recognized, thereby enhancing concern about its conservation status. The remaining four species have even smaller ranges, some of which are degraded or threatened by human activities. Whereas much of the range of A. stebbinsi is already compromised by urban development, the conservation implications for the other three new species are even more striking because of their very limited distributions. Anniella grinnelli is known from a few sites in the southern San Joaquin Valley, an area that has been greatly modified by urban and agricultural development …. Anniella grinnelli persists in small patches within the Bakersfield city limits, but some of the populations we collected were extirpated by development during the course of this study. The type locality at the Sand Ridge Preserve is a secure site that will help ensure the species survival. Anniella alexanderae is known from two sites at the base of the Temblor Mountains, and should be considered rare pending further study. Finally, Anniella campi is known from just three sites. This species may be restricted to the vicinity of potentially fragile springs in canyons that open into the Mojave Desert and so warrants careful monitoring. Additional research into the distribution, contact zones, and diversity of Anniella is clearly needed."

Papenfuss and Parham (2013)

|

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Anniellidae |

North American Legless Lizards |

Boulenger 1885 |

Genus

|

Anniella |

North American Legless Lizards |

Gray, 1852 |

Species

|

grinnelli |

Bakersfield Legless Lizard |

Papenfuss and Parham, 2013 |

| Original Description |

Theodore J. Papenfuss and James F. Parham Breviora, Number 536:1-17. 2013.

|

| Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Anniella -

Latin - annela = ringed +

Latin - ella = little

Refers to little rings in the pattern. Or possibly an honorific for someone named "Annie" or a coined name.

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

grinnelli -

"This species is named after Joseph Grinnell (1877–1939; Fig. 6), the first director of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at the University of California at Berkeley. Joseph Grinnell published hundreds of scientific papers based on his extensive collecting and surveys in western North America, and developed the Grinnell Method of note taking that has become the standard for natural history observations."

Papenfuss and Parham (2013)

|

| Related or Similar California Lizards |

Anniella alexanderae - Temblor Legless Lizard

Anniella campi - Big Spring Legless Lizard

Anniella pulchra - Northern Legless Lizard

Anniella stebbinsi - San Diego Legless Lizard

|

| More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Turtles and Lizards of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Jones, Lawrence, Rob Lovich, editors. Lizards of the American Southwest: A Photographic Field Guide. Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2009.

Smith, Hobart M. Handbook of Lizards, Lizards of the United States and of Canada. Cornell University Press, 1946.

2 Parham, James F., Theodore J. Papenfuss. High genetic diversity among fossorial lizard populations (Anniella pulchra) in a rapidly developing landscape (Central California) Conserv Genet DOI 10.1007/s10592-008-9544-y

Received: 12 September 2007 / Accepted: 15 February 2008. Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2008

3 Four New Species of California Legless Lizards (Anniella)

Author(s): Theodore J. Papenfuss and James F. Parham

Source: Breviora, Number 536:1-17. 2013.

Published By: Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University

URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3099/MCZ10.1

Joseph Grinnell and Charles Lewis Camp. A Distributional List of the Amphibians and Reptiles of California. University of California Publications in Zoology Vol. 17, No. 10, pp. 127-208. July 11, 1917.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

California Special Animals List Notes:

"Legless lizards (Anniella spp.) in California were traditionally considered one species, but are now considered five species (Pappenfuss and Parham, 2013). The prior (Jennings and Hayes, 1994) and current (Thompson et al. 2016) Species of Special Concern (SSC) projects evaluated the traditional single species taxon and determined all legless lizards in California to be an SSC. Therefore, the SSC status is carried over to the new taxon concepts until further SSC evaluation."

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G2G3 |

Imperiled-Vulnerable |

| NatureServe State Ranking |

S2S3 |

Imperiled-Vulnerable

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

SSC |

California Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

None |

|

|

|