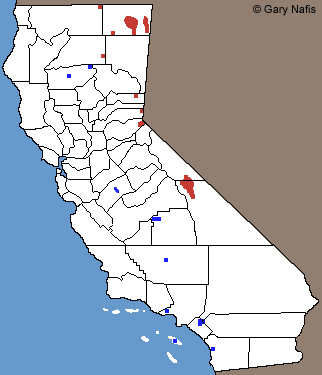

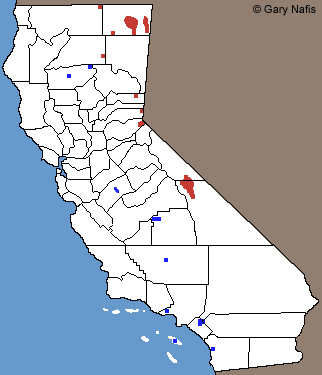

Red

Red : Probable historic range in California

Blue: Past and present introduced populations

Click on the map for a topographical view

Map with California County Names

Listen to this frog:

A short example

|

This frog is native to California but most native populations are now extinct.

There are also populations of Northern Leopard Frogs that have been introduced from out of the state.

|

| |

|

|

| |

Adult found in California

© Patrick Briggs

|

|

| |

|

|

| Northern Leopard Frogs From Outside California |

|

|

|

Adult, green phase,

Grant County, Washington |

Adult, brown phase,

Grant County, Washington |

Adult, green phase,

Grant County, Washington |

|

|

|

Adult, brown phase,

Grant County, Washington |

Adult, brown phase,

Grant County, Washington |

Adult, green phase,

Grant County, Washington |

|

|

|

Adult, green phase,

Grant County, Washington |

Underside of Adult |

Groin of adult |

|

|

|

| Adult, Washington County, Utah |

Adult, Washington County, Utah |

Adult, Washington County, Utah |

|

|

|

Adult, Washington County, Utah

|

Adult, Washington County, Utah |

Adult, Grant County, Washington |

|

|

|

| Adult, Manitoba, Canada |

Calling adult male, Manitoba, Canada |

Adult, Manitoba, Canada |

| |

|

|

| |

Adult, DuPage County, Illinois

© Mark Gary |

|

| |

|

|

| Reproduction, Eggs and Tadpoles |

|

|

|

Eggs in pond, Grant County, Washington

© 2004 William Leonard

|

Eggs, Washington County, Utah |

Eggs, Washington County, Utah |

|

|

|

Eggs with recently hatched tadpoles,

Washington County, Utah |

Eggs, Manitoba, Canada |

Eggs, Manitoba, Canada |

|

|

|

| Eggs, Manitoba, Canada |

Eggs in a marsh, Manitoba, Canada |

Tadpole, Grant Co., Washington

© 2000 William Leonard

|

| |

|

|

| |

Close-up of breeding pond during the April breeding season, Grant County, Washington |

|

| |

|

|

| Habitat |

|

|

|

Habitat - agricultural canal, Merced County

|

Habitat, Tule Lake, 4,100 ft.,

Siskiyou count |

Habitat, Tule Lake, 4,100 ft.,

Siskiyou count |

|

|

|

Possible former Habitat,

Owens River, Inyo County

|

Possible former Habitat,

Owens Valley, Inyo County |

Habitat, Merced County © Casey Moss |

More pictures of this frog and its habitat in the Northwest, Southwest, and Manitoba, Canada.

|

| Short Videos |

|

|

|

| Two videos of a Northern Leopard Frog calling on a sunny April afternoon in Grant County, Washington. Red-winged blackbirds and yellow-headed blackbirds and other birds are heard in the background. Calling was sporadic over a long period of time, so these calls have been edited together from longer videos. |

A pond with a few of the last remaining Northern Leopard Frogs in Grant County, Washington. |

|

|

|

| An adult male calls during daylight from a marsh in Manitoba, Canada in May. Other Northern Leopard Frogs, Boreal Chorus Frogs, and Canadian Toads are heard in the background along with several birds. |

A Northern Leopard Frog on the rocky shore of a river in Washington County, Utah. |

Several egg masses at the edge of a marsh in Manitoba Canada in May. |

|

|

|

| Description |

| |

| Size |

Adults are 2 - 4.75 inches in length from snout to vent (5.1 - 11.1 cm). (Stebbins & McGinnis, 2012)

|

| Appearance |

| A medium-sized slender frog with a narrow head and long legs. |

| Color and Pattern |

Green, tan, or brown above, with dark brown oval spots with well-defined edges and pale borders.

Males and females are both creamy white below, without any dark pigmentation.

Cream-colored well-defined dorsolateral folds extend from the shoulders to the rump.

The upper jaw has a whitish stripe.

|

| Male/Female Differences |

Females are larger, growing up to 4.75 inches in length (11.1 cm).

Males grow up to 3.15 in. (8 cm).

During the breeding season, the bases of the thumbs of male frogs is dark and swollen and the skin between their jaw and shoulders is loose where the vocal sacs protrude. |

| Young |

| Young have few or no spots. |

| Larvae (Tadpoles) |

Tadpoles are brown or grey with small gold spots, creamy

below with a bronzy sheen and visible guts, and grow up to 3.5 in. in length (8.7 cm.)

|

| Life History and Behavior |

| Activity |

Diurnal and nocturnal.

Very well-adapted to cold conditions.

Often strays far from water in summer into a variety of habitats including hay fields and grassy woodlands, as long as there is sufficient vegetative cover for concealment.

Adults and juveniles may wander around in wet weather.

Hibernates in winter, typically under large deep bodies of water that do not freeze to the bottom, positioned under rocks or logs or in pits, or buried under mud. Frogs will die if the water does not contain enough oxygen or if they freeze more than approximately 8 hours. |

| Defense |

These frogs avoid predators by sitting still to avoid detection, by jumping into water and by hiding in vegetation.

Tadpoles reduce their activity when threatened. |

Territoriality

|

"Because egg masses are typically confined to an area much smaller than that occupied by calling males, Pace (1974) suggested that relatively few males are involved in fertilizing egg masses. Short, terminal sounds in the call sequence have an aggressive or spacing function among males (Pace, 1974). These observations suggest territoriality among calling males." (J. Rorabaugh in Lannoo, 2005) |

| Longevity |

| Longevity has been recorded as long as 9 years in captivity. |

| Voice (Listen) |

A moderately loud low guttural snore-like rattle, which has been compared to a small motor boat engine.

Males call at night and occasionally during the day, using paired vocal sacs found between the jaw and shoulders.

Often screams when captured or when startled and jumping into water. |

| Diet and Feeding |

Eats invertebrates, leeches, fish, amphibians, snakes, and small birds.

Typically, a frog sits and waits until prey comes close. When the frog sees the prey moving, it moves and lunges after it, using its large sticky tongue to catch the prey and bring it into the mouth to eat. Eating takes place out of the water. Watch a slow-motion feeding video here.

Tadpoles feed by grazing on plant tissue and bacteria by scraping plant surfaces with their mouth parts. Algae and detritus and possibly carrion are also consumed. |

| Reproduction |

Reproduction is aquatic.

Fertilization is external, with the male grasping the back of the female and releasing sperm as the female lays her eggs.

The reproductive cycle is similar to that of most North American Frogs and Toads. Mature adults come into breeding condition and move to ponds or ditches where the males call to advertise their fitness to competing males and to females. Males and females pair up in amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally. The adults leave the water and the eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

Calling, mating and egg-laying occurs for a short period anytime from March to July after the snow melts.

(Breeding has also been recorded in September and October in New Mexico.)

Females become reproductively mature at 2 - 3 years, males at 1 - 2 years.

Mature adults come into breeding condition after emerging from hibernation and move to breeding waters from winter hibernacula, unless they hibernate and breed in the same pond.

Breeding habitat is varied, and includes quiet waters along streams and rivers, permanent ponds and lakes, cattle ponds, agricultural ditches, flooded fields, and beaver ponds. Temporary ponds and pools are also used. Bodies of water with or without vegetation are both used.

Males gather at the breeding site and call from the water at night and sometimes during the day to advertise their fitness to competing males and to females.

Males and females pair up in amplexus in the water where the female lays her eggs as the male fertilizes them externally.

The adults leave the water and the eggs hatch into tadpoles which feed in the water and eventually grow four legs, lose their tails and emerge onto land where they disperse into the surrounding territory.

|

| Eggs |

Females lay eggs once per year.

Eggs are laid in densely-packed, flat, rounded clusters the size of a grapefruit - around 4.5 in. (11.5 cm) in diameter, and are attached to vegetation under water, or rarely, left to lie on the bottom of still water. Several egg masses may be attached together communally.

Egg masses of between 645 and 7,648 eggs have been reported.

Eggs hatch into tadpoles in 2 - 17 days, depending on temperature. |

| Tadpoles and Young |

Tadpoles transform into frogs 3 - 6 months after eggs are laid.

At one location, tadpoles metamorphosed 50 days after hatching. Tadpoles have also been observed overwintering.

Tadpoles are diurnal and do not form schools.

Newly-metamorphosed juveniles are about 1 inch. long. (2.5 cm.)

Juveniles disperse from breeding waters into the surrounding countryside.

|

| Habitat |

Inhabits grassland, wet meadows, potholes, forests, woodland, brushlands, springs, canals, bogs, marshes, reservoirs.

Generally prefers permanent water with abundant aquatic vegetation.

|

| Geographical Range |

The native range of L. pipiens is much of Canada and most of the northern half of the United States, with scattered locations from the northwest south through California and Arizona almost to the Mexican border in New Mexico. (See map below.)

My California distribution map attempts to show where native populations of the species might have occured in the state, as well as showing some of the locations where the frog has been recorded. L. pipiens is most likely no longer present at most of the locations shown on the map. Currently it seems likely to be present only at locations in the Central Valley and possibly near Pine Creek in Inyo County and at the Tule Lake Wildlife Refuge in Siskiyou County (where it was last seen in the 1990s.)

Some L. pipiens introduced into the Central Valley in Merced County are now (2021) tentatively thought to be

L. sphenocephalus, so it's possible L. pipiens is not present there after all. Leopard frogs were introduced to the area decades ago when several species, including L. sphenocephalus, were all recognized as L. pipiens. Difficulties in differentiating species of leopard frogs have likely caused misidentifications.

L. pipiens is native to northern California, and they have also been introduced at other locations in California (and throughout the west) in the past 100 years, possibly partly due to the widespread use of the species for study and dissection in biology classes and the escape or intentional release of unused specimens into the wild.

Historic populations in California existed at scattered locations below 6,500 ft. (1981 m.) in the far Northeast

part of the state in Siskiyou and Modoc counties, in the northern Owens Valley, and possibly near Lake Tahoe. The origin of the lake Tahoe population is questionable, because leopard frogs were transplanted from a reservoir in Nevada to the southwest shore of Lake Tahoe in the early 20th century, in order to provide a source of fresh frog legs for a local restaurant. (Jennings 2004)

Jennings and Fuller determined in their 2004 report on the distribution of leopard frogs in California that Northern leopard frogs are "...native to the region east of the Sierra Nevada-Cascade crest.... Early in the 20th century (Northern leopard frogs) expanded their ranges into favorable habitats created by water diversions and large-scale irrigation projects. Since the 1970s, northern leopard frogs seem to have disappeared from most of their historic range.... Northern leopard frogs of unknown origin were introduced into El Dorado, Kern, Los Angeles, Merced, San Francisco, Sierra, Tehama, and Tulare counties between 1905 and 1970. Several of these introduced populations experienced rapid growth and range expansions before completely disappearing. Except for a small population of northern leopard frogs present in Merced County, all of these introduced populations have apparently perished after persisting for varying periods of 5 -25 years."

According to Storer (1925) "An attempted introduction of pipiens in the northern Sacramento Valley was made in 1918 when stocks (source unknown) were planted on ranches east of Red Bluff (Elliot and Hickman ranches) and at Battle Creek Meadows [=Mineral Postoffice], altitude 4500 ft. Mr. D. G. Maclise, who was instrumental in placing these frogs, reported that in 1920 the frogs near Red Bluff were "thriving"; but efforts to obtain specimens in 1924 were unavailing. Pipiens is the species of frog used most commonly in physiological laboratories, and is also sought commercially for 'frogs-legs'; other attempts of planting may therefore have been made within California."

|

|

| Elevational Range |

Found from sea level to 11,000 ft. (3,350 m.)

|

| Notes on Taxonomy |

In 2006, Frost et al divided North American frogs of the family Ranidae into two genera, Lithobates and Rana. Rana is still used in many existing references.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025 SSAR Scientific and Standard English Names List comment:

"Many of the experimental works on nominal “Rana pipiens” are actually based on animals collected in northwestern Mexico, Lithobates forreri and L. magnaocularis."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Alternate and Previous Names (Synonyms)

Rana pipiens - Northern Leopard Frog (Stebbins 1985, 2003, Stebbins & McGinnis 2012)

Rana pipiens - Leopard Frog (Stebbins 1954, 1966)

Rana pipiens pipiens (Wright and Wright 1949)

Rana pipiens - Leopard Frog (Storer 1925)

Rana pipiens (Schreber 1782)

|

| |

| Conservation Issues (Conservation Status) |

A California Species of Special Concern.

Protected from take with a sport fishing license in 2013.

This species has experienced severe declines in the west, including most historical localities in California, Washington, Oregon, Arizona, New Mexico, and Western Montana. Declines have also occurred in Nevada, Wyoming, and Idaho. In other areas across the country, some populations are doing well, while others have also shown declines.

Northern Leopard Frogs are absent and possibly extirpated from about 95 percent of their historical range in California. Recent records are from one national wildlife refuge near the Oregon border and in the Owens Valley, northwest of Bishop. Most of the habitat previously inhabited in the Modoc and Owens Valley regions have been severely altered by agriculture and grazing, and introduced predators such as bullfrogs, crayfish, and exotic fishes may have negatively affected populations of R. pipiens. Disease, parasites, agricultural chemical pollution, and UV-B radiation have all been reported to cause declines and malformations of adult frogs and tadpoles. |

|

| Taxonomy |

| Family |

Ranidae |

True Frogs |

Rafinesque, 1814 |

| Genus |

Lithobates |

American Water Frogs |

Fitzinger, 1843 |

| Species |

pipiens |

Northern Leopard Frog

|

Schreber, 1782 |

|

Original Description |

Schreber, 1782 - Naturforscher, Vol. 18, p. 185, pl. 4

from Original Description Citations for the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Meaning of the Scientific Name |

Lithobates - Greek - Litho = a stone, bates = one that walks or haunts

pipiens - Latin = peeping - the collector heard Spring Peepers and thought that the loud whistle of that species came from the larger frog.

from Scientific and Common Names of the Reptiles and Amphibians of North America - Explained © Ellin Beltz

|

|

Related or Similar California Frogs |

Lithobates berlandieri

Lithobates catesbeianus

Lithobates yavapaiensis

Rana draytonii

Rana aurora

Rana boylii

Rana cascadae

Rana pretiosa

Rana muscosa

|

|

More Information and References |

California Department of Fish and Wildlife

AmphibiaWeb

Jennings, Mark R., and Michael M. Fuller. 2004. Origin and distribution of leopard frogs, Rana pipiens complex, in California. California Fish and Game 90(3):119-139.

Hansen, Robert W. and Shedd, Jackson D. California Amphibians and Reptiles. (Princeton Field Guides.) Princeton University Press, 2025.

Stebbins, Robert C., and McGinnis, Samuel M. Field Guide to Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Revised Edition (California Natural History Guides) University of California Press, 2012.

Stebbins, Robert C. California Amphibians and Reptiles. The University of California Press, 1972.

Flaxington, William C. Amphibians and Reptiles of California: Field Observations, Distribution, and Natural History. Fieldnotes Press, Anaheim, California, 2021.

Nicholson, K. E. (ed.). 2025. Scientific and Standard English Names of Amphibians and Reptiles of North America North of Mexico, with Comments Regarding Confidence in Our Understanding. Ninth Edition. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. [SSAR] 87pp.

Samuel M. McGinnis and Robert C. Stebbins. Peterson Field Guide to Western Reptiles & Amphibians. 4th Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2018.

Stebbins, Robert C. A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians. 3rd Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003.

Behler, John L., and F. Wayne King. The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Powell, Robert., Joseph T. Collins, and Errol D. Hooper Jr. A Key to Amphibians and Reptiles of the Continental United States and Canada. The University Press of Kansas, 1998.

Macey, J. Robert and Theodore Papenfuss."Herpetology." The Natural History of the White-Inyo Range Eastern California.

Ed. Clarence Hall. University of California Press, 1991.

Corkran, Charlotte & Chris Thoms. Amphibians of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. Lone Pine Publishing, 1996.

Jones, Lawrence L. C. , William P. Leonard, Deanna H. Olson, editors. Amphibians of the Pacific Northwest. Seattle Audubon Society, 2005.

Leonard et. al. Amphibians of Washington and Oregon. Seattle Audubon Society, 1993.

Nussbaum, R. A., E. D. Brodie Jr., and R. M. Storm. Amphibians and Reptiles of the Pacific Northwest. Moscow, Idaho: University Press of Idaho, 1983.

Robert Powell, Roger Conant, and Joseph T. Collins. Peterson Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America. Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2016.

Conant, Roger, and Joseph T. Collins. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians Eastern and Central North America.

Third Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998.

American Museum of Natural History - Amphibian Species of the World 6.2

Bartlett, R. D. & Patricia P. Bartlett. Guide and Reference to the Amphibians of Western North America (North of Mexico) and Hawaii. University Press of Florida, 2009.

Elliott, Lang, Carl Gerhardt, and Carlos Davidson. Frogs and Toads of North America, a Comprehensive Guide to their Identification, Behavior, and Calls. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009.

Lannoo, Michael (Editor). Amphibian Declines: The Conservation Status of United States Species. University of California Press, June 2005.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of California Press Berkeley, California 1925.

Wright, Albert Hazen and Anna Wright. Handbook of Frogs and Toads of the United States and Canada. Cornell University Press, 1949.

Storer, Tracy I. A Synopsis of the Amphibia of California. University of Califonia Publications in Zoology Volume 27, The University of California Press, 1925.

Davidson, Carlos. Booklet to the CD Frog and Toad Calls of the Pacific Coast - Vanishing Voices. Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 1995.

|

|

|

The following conservation status listings for this animal are taken from the April 2024 State of California Special Animals List and the April 2024 Federally Listed Endangered and Threatened Animals of California list (unless indicated otherwise below.) Both lists are produced by multiple agencies every year, and sometimes more than once per year, so the conservation status listing information found below might not be from the most recent lists. To make sure you are seeing the most recent listings, go to this California Department of Fish and Wildlife web page where you can search for and download both lists:

https://www.wildlife.ca.gov/Data/CNDDB/Plants-and-Animals.

A detailed explanation of the meaning of the status listing symbols can be found at the beginning of the two lists. For quick reference, I have included them on my Special Status Information page.

If no status is listed here, the animal is not included on either list. This most likely indicates that there are no serious conservation concerns for the animal. To find out more about an animal's status you can also go to the NatureServe and IUCN websites to check their rankings.

Check the current California Department of Fish and Wildlife sport fishing regulations to find out if this animal can be legally pursued and handled or collected with possession of a current fishing license. You can also look at the summary of the sport fishing regulations as they apply only to reptiles and amphibians that has been made for this website.

The State of California listings shown below apply to native populations only of Rana pipiens.

The Natureserve and IUCN Global rankings apply to all populations worldwide.

California Special Animals List Notes:

Formerly Rana pipiens; Frost et al. (2006. The Amphibian Tree of Life. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 297: 1-370) placed this species in the genus Lithobates (Fitzinger 1843).

|

| Organization |

Status Listing |

Notes |

| NatureServe Global Ranking |

G5 |

Secure |

| NatureServe State Ranking |

S2 |

Imperiled

|

| U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) |

None |

|

| California Endangered Species Act (CESA) |

None |

|

| California Department of Fish and Wildlife |

SSC |

Species of Special Concern |

| Bureau of Land Management |

None |

|

| USDA Forest Service |

None |

|

| IUCN |

LC |

Least Concern |

|

|

|